Dialogue is the most misunderstood tool in a screenwriter’s kit. Everyone thinks they know it because everyone talks. But good dialogue is compressed intention, conflict with manners, and characters revealing themselves even as they try not to.

If you’ve ever been told your dialogue is on the nose, too chatty, or doesn’t sound cinematic, this guide is for you. In today’s blog, we’re going to strip dialogue down to its professional purpose, look at why screenplay dialogue plays by different rules than real speech, and explore how great writers make words shoot.

So, let’s get started.

What is Dialogue in a Screenplay?

Dialogue in a screenplay is intentional character interaction designed to advance the plot, reveal character, and create the illusion of realism.

In professional screenwriting terms, dialogue is not what characters say, but what they do with words. Every line is a choice made under pressure. Dialogue exists to move the story forward, deepen our understanding of who these people are, and guide the audience’s emotional response.

Unlike prose, screen dialogue must operate in real time. Unlike theatre, it must survive editing, performance, and subtext-heavy visual storytelling. Dialogue is therefore economical by necessity. It should feel spontaneous while being ruthlessly engineered.

If a line of dialogue doesn’t change the direction of the scene, reveal something new about a character, or sharpen the dramatic situation, it probably doesn’t belong in the script.

Dialogue vs. Speech

Okay, so this is where many emerging writers go wrong. While real speech is messy, dialogue is curated.

In real life, we ramble, repeat ourselves, interrupt, fill silences with noise, and say things we don’t mean. If you transcribed actual conversations and put them on screen, the result would be unbearable.

Scripted dialogue imitates speech patterns without copying them. It removes redundancy while also preserving rhythm. It keeps hesitation when it reveals vulnerability but cuts it when it kills momentum.

Think of it this way: speech is what people day, and dialogue is what the audience needs to hear. The job we have as screenwriters is to bridge the gap invisibly.

So, why must scripted words count more?

Well, in a screenplay words compete with performance, camera movement, editing, sound design, music, and silence. Which means dialogue is never working alone. The more words you use, the more you risk crowding out the cinematic language.

Professional dialogue tends to be shorter than you think, sharper than real life, and loaded with implication. A single line can establish power dynamics, history, conflict, and tone if it’s doing its job properly. If you need three lines to explain what one look could communicate, the dialogue is overreaching.

The Three Functions of Successful Dialogue

Successful dialogue can be defined by three distinct characteristics:

1. Advance the Plot

Every scene exists because something needs to change. Dialogue is one of the primary engines that causes that change. Plot advancing dialogue does four things:

- Introduces new information

- Forces a decision

- Escalates conflict

- Closes off options

Crucially it should do this without sounding like exposition. The audience should feel momentum.

A good test is that if this conversation were removed, would the story still make sense? If the answer is yes, the dialogue isn’t pulling its weight.

2. Reveal Character

Characters reveal themselves not by what they say, but by what they avoid saying, how they say things, and who they say them to.

Two characters can deliver the same information and reveal completely different inner lives. One hedges, one attacks, one jokes, and one deflects.

Dialogue reveals:

- Values

- Fear

- Status

- Desire

- Self-description

The best dialogue lets the audience infer character rather than spelling it out. If a character has to tell us who they are, the writing has already failed.

3. Build Realism

This is the illusion part. Dialogue doesn’t need to be realistic. Instead, it needs to feel real. That means natural rhythms, consistent voice, and emotional truth.

Realism comes from specificity and a single odd phrasing or unexpected word choice can make a character feel alive. When dialogue fails at realism, the audience stops believing in the world, and once belief is broken, it’s very hard to win back.

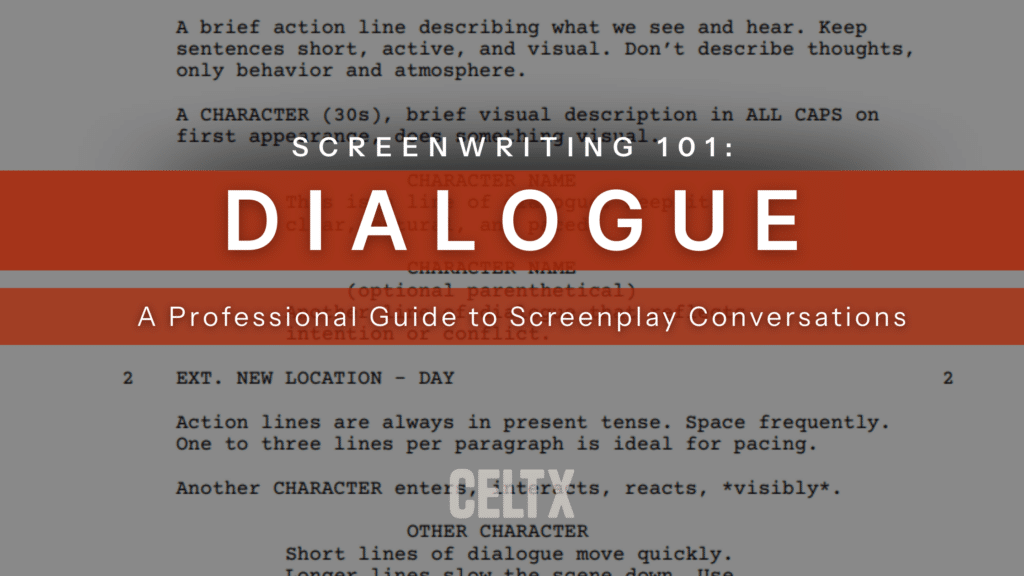

How to Format Dialogue for Stage and Screen

Formatting doesn’t make your dialogue better, but bad formatting can absolutely get your script ignored.

This is one of those unglamorous realities of professional writing: readers expect scripts to look right before they even start judging whether they are right. Clear, industry-standard formatting signals competence, confidence, and respect for the reader’s time.

Screenplay Dialogue Formatting: Step by Step

Screenplay dialogue formatting follows a clear visual logic. Here’s how it works, from the top down.

Step 1| Enter the Character

- Write the character’s name in ALL CAPS.

- Centre it on the page according to standard screenplay margins.

- Use the same name consistently throughout the script.

This instantly tells the reader who is speaking and keeps the eye moving down the page.

Step 2 | Decide If a Parenthetical Is Necessary

- Place parentheticals directly beneath the character name.

- Use them only when the line could be misinterpreted without clarification.

Examples of useful parentheticals include delivery shifts (e.g. ironic, under breath, interrupting). Avoid emotional instructions. Actors will find those themselves. If you’re using parentheticals on most lines, the dialogue itself probably needs rewriting.

Step 3 | Write the Dialogue Block

- Keep dialogue within standard screenplay margins.

- Aim for short, playable lines rather than long speeches.

- Break up longer thoughts into multiple lines where possible.

Visually, dialogue should feel breathable. If it forms a solid rectangle on the page, it’s usually too dense.

Step 4 | Control Rhythm with White Space

White space is pacing, and rapid back-and-forth exchanges create momentum because they look fast. Single-line responses hit harder than paragraphs. Silence between lines can be as expressive as speech.

Formatting lets you control how the scene feels before a word is spoken aloud.

Stage Play Dialogue Formatting: Step by Step

Stage dialogue prioritises clarity and performance over speed.

Step 1 | Name the Speaker

- Character names are usually capitalised and placed to the left.

- Formatting conventions vary, but consistency is key.

Step 2 | Allow for Longer Speech

Plays accommodate:

- Extended dialogue passages

- Monologues

- Fewer interruptions

This reflects the reality of live performance, where language must carry the scene without editorial cuts.

Step 3 | Use Pauses and Beats Deliberately

Stage dialogue often includes written pauses or beats. These should still be purposeful, not habitual.

If every speech contains pauses, they stop meaning anything.

Step-by-Step Checklist Before You Move On

Before leaving a dialogue scene, ask:

- Can I identify the speaker instantly?

- Is every parenthetical doing essential work?

- Does the dialogue look as fast or slow as the scene should feel?

- Are longer passages justified by performance needs?

If the answer to any of these is no, revise.

Stage Play Dialogue Formatting

Stage dialogue follows different priorities. Plays are designed to be experienced live, without editing, close-ups, or cinematic shorthand. As a result:

- Dialogue is often less tightly constrained by width.

- Longer speeches and monologues are more acceptable.

- Formatting can vary depending on tradition, publisher, or theatre company.

Where screen dialogue is about economy, stage dialogue is about endurance. Actors must hold the audience’s attention in real time, often without visual cutaways to relieve verbal density.

Why Formatting Affects How Dialogue Is Read

Formatting shapes how the dialogue is imagined. A dense block of dialogue feels heavy before it’s even read. Short lines feel punchy. Quick exchanges feel faster because they look faster.

Readers subconsciously associate clean formatting with control. When dialogue formatting is sloppy, inconsistent, or unconventional without reason, it creates friction, and friction kills momentum. This is why many experienced writers treat formatting as invisible craft. If the reader notices it, something has gone wrong.

When (and When Not) to Use Parentheticals

Parentheticals are often overused by newer writers trying to control performance.

Used well, they:

- Clarify intention when a line could be misread

- Indicate a sharp tonal shift

- Prevent confusion in fast-paced dialogue

But when used poorly, they:

- Micromanage actors

- Explain subtext that should be implicit

- Interrupt the rhythm of the page

A good rule of thumb: if a parenthetical explains emotion, cut it. If it clarifies meaning, it may be necessary.

Linking Craft to Format

Formatting part of the storytelling language. A well-formatted dialogue exchange tells the reader how fast the scene moves, where emphasis lies, and when silence matters. It supports the dialogue rather than competing with it.

If you’re unsure about industry standards or want a breakdown by medium, this is where a dedicated guide is invaluable. Check out our How to Format Dialogue in a Screenplay blog for a detailed rundown.

Case Study | 12 Angry Men Play Script vs Screenplay

Few works illustrate the difference between stage and screen dialogue formatting better than 12 Angry Men. Originally written by Reginald Rose as a teleplay and later adapted into a stage play and the iconic 1957 screenplay, it offers a clean, practical comparison of how the same dramatic engine is formatted differently depending on medium.

12 Angry Men as a Stage Play

In the stage version, dialogue carries almost the entire dramatic load.

Key characteristics:

- Longer dialogue blocks are common, especially during arguments and votes.

- Characters are often allowed to complete full thoughts without interruption.

- Formatting prioritises clarity for performance rather than speed for reading.

Because the audience is confined to a single space with no cuts, the language must sustain tension continuously. Dialogue is written to hold the room. Pauses, beats, and rhetorical build-ups are essential, and the formatting accommodates that endurance.

On the page, this means denser dialogue that would feel heavy in a screenplay but works perfectly in a live theatrical context.

12 Angry Men as a Screenplay

In the screenplay, the same conflicts are expressed with greater fragmentation.

Notable differences:

- Dialogue is broken into shorter exchanges.

- Interruptions and overlaps are more frequent.

- Silence, reaction shots, and physical movement do more of the storytelling work.

The screenplay version relies on the camera to relieve verbal pressure. A look, a cut, or a shift in blocking can replace several lines of spoken argument. As a result, the dialogue formatting is leaner, faster, and visually airier on the page.

Even when speeches are emotionally charged, they’re shaped to feel playable within a cinematic rhythm.

Dialogue Beyond Words

Some of the most powerful dialogue moments contain very few words. Pauses, looks, interruptions, and actions that contradict speech.

Non-verbal dialogue is where subtext lives. It’s the space between what’s said and what’s meant. When characters say one thing and do another, the audience leans in.

Examples include:

- A character agreeing verbally while physically retreating

- Silence used as refusal

- A delayed response that signals emotional damage

If dialogue is the text, non-verbal behaviour is the truth underneath it. Great writers understand when to shut their characters up and let the scene speak for itself.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

No. Some scenes are more powerful without it. Visual storytelling, action, and silence can often communicate more efficiently than words. Dialogue should enter only when it adds something that images alone cannot.

When the dialogue starts explaining things the audience already understands or worse, things they should feel, it’s too much. If characters are saying exactly what they think and feel, the scene is likely overwritten.

Dialogue is interaction. Monologue is expression. A monologue can be powerful, but it freezes the dramatic exchange. That’s why they’re used sparingly in screenwriting. If a monologue doesn’t change something in the scene, it’s indulgence.

Conclusion

Great dialogue is designed, pressured, and purposeful. It sounds effortless because it isn’t. Every line should feel like it was chosen under fire. If you want your dialogue to improve, stop asking whether it sounds real. Ask whether it does something.

Stop fighting with margins.

Let Celtx handle your dialogue formatting so you can focus on the voice.

Up Next:

10 Tips for Writing Dialogue that Feels Real

Great dialogue sounds natural while doing a lot of hidden work. Learn how to write conversations that reveal character, move the story forward, and feel authentic on the page.