Monologues are the tightrope of screenwriting. Nail one, and the audience leans in like you’ve whispered a secret straight into their soul. Botch it, and suddenly the room feels like you’ve handed out pamphlets at a party. Nobody asked for this, and everyone quite frankly wants to leave.

But when you get monologues, I mean truly get them and understand their power, their purpose, and the craft behind them you unlock one of the most potent dramatic tools available to writers. A good monologue can break a character open like a geode. It can turn a scene. It can flip audience expectation. And it can articulate everything a character has swallowed for the past 85 pages.

In today’s blog we’ll be getting under the skin of a monologue and talking about how to write them, so they don’t just sit on the page like a block of text but burn a hole in the script.

So, without further ado…

What is a Monologue?

A monologue is a character’s uninterrupted moment of speech. It’s a spotlight moment where the audience is invited inside their head, heart, or strategy.

Crucially, a monologue is not simply ‘a long line of dialogue’. It is a purposeful decision by the writer to give a character the floor.

It might be:

- A confession

- A confrontation

- A plea

- A strategy speech

- An emotional release

- A lie (which is sometimes even better!)

The spotlight is on the character speaking and on the truth their moment demands.

The Purpose: Why Give a Character a Monologue?

If you ever find yourself writing a monologue because the scene ‘needs more energy’ or ‘some background info,’ take your hands off the keyboard and step away, sip water, and maybe even reevaluate your life choices.

Okay, maybe the latter is a little bit extreme. Anyhow, it’s important to remember that a monologue must do one of two things. It must either reveal something (a truth, feat, motive, contradiction) or change something (a dynamic, stakes, a character’s trajectory, the audience’s perspective).

And the golden rule is: A monologue is action, not exposition! When I say action, don’t mean physical movement. I mean a choice, a risk, or the willingness to confront a piece of internal conflict or external conflict.

Exposition only tells the audience what happened, while action tells them what matters. If your monologue doesn’t shift the tectonic plates of the scene in some way, it isn’t a monologue!

Write dialogue that grabs the audience and never lets go with Celtx.

Start writing today, it’s free.

Monologue vs. Soliloquy vs. a Dialogue-Heavy Scene

It’s easy to confuse the monologues, soliloquies and dialogue-heavy scenes, so let’s clear the air!

Monologue

As we know, a monologue is where a character speaks at length to another character, group, or the room. It’s motivated by the situation.

Soliloquy

A character speaks their inner thoughts aloud to themselves or the audience. Think Shakespeare, voiceovers, or breaking the fourth wall. The key difference from a monologue is that a soliloquy doesn’t require another character’s presence.

Dialogue-Heavy Scenes

This is not a monologue. Instead, this is just people talking, a lot! Rapid-fire conversations, overlapping lines, and arguments. None of them qualify as a monologue unless one person takes the floor uninterrupted.

If other characters chime in, react, or interrupt, it stops being a monologue. Simple as that!

Formatting a Monologue

Okay, so let’s talk mechanics. A monologue that looks like a brick wall on the page will immediately intimidate readers before the actor even breathes life into it.

To effectively format a monologue:

Keep Action Lines Minimal

A monologue is the verbal centerpiece, so action lines should be used sparingly and strategically.

Use action lines to indicate shifts, mark emotional beats, and when the speaker interacts with their environment.

Use (CONT’D) Intentionally

If a character speaks for several paragraphs separated by action lines, most screenwriting software (including Celtx) will tag it with (CONT’D). This is purely for clarity and reading rhythm.

You do not need (CONT’D) for every long line of dialogue. Only when the dialogue is interrupted by action lines or reactions.

Make sure to break your monologue into digestible fragments and give them white space. Your reader will thank you.

Formatting Example

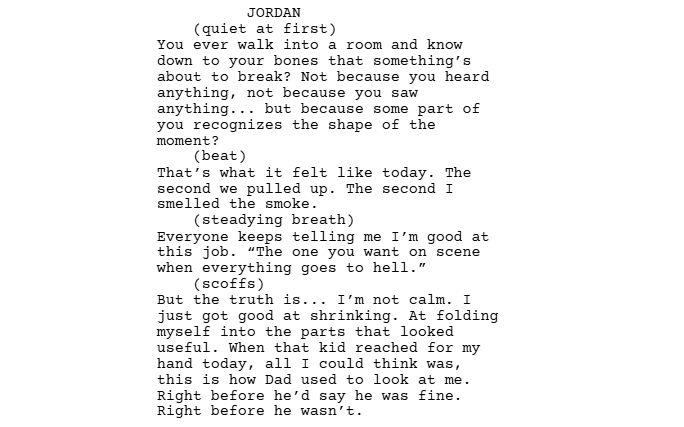

Let’s see these formatting principles in action. Here is a scene written in Celtx. It takes place between Jordan, a paramedic who’s been avoiding a critical conversation, and Reese, their partner (professionally and personally) who has started noticing Jordan’s behavior unravelling. The two are alone in the back of the ambulance after a call that hit too close to home.

Jordan finally stops deflecting.

Why This Monologue Works

It starts controlled, then unravels. Jordan begins contained but as the truth emerges, the structure mirrors emotional escalation.

While there are parentheticals, they don’t direct the actor. Small cues can help actors find a moment’s emotional rhythm without dictating their performance.

Each paragraph shift signals a new emotional beat, a change in memory or an internal collapse. In this case, the monologue exposes the trauma Jordan masks professionally.

Thus, it changes the scene’s trajectory. After this, Reese will have no choice to respond, the dynamic between the two characters permanently altered.

The Writer’s Toolkit

Parentheticals

Parentheticals are to monologues what seasoning is to cooking. You can use just enough to elevate, not overwhelm.

Parentheticals can:

- Indicate emotional shifts

- Clarify intention

- Change pacing (whispers, beat, under breath)

- Prevent misinterpretations

Parentheticals cannot:

- Direct the actor

- Describe physical action

- Replace good writing

Line Breaks

Use line breaks to control rhythm. If you want a line to hit like a punchline, give it its own space on the page. Or, if you want to show hesitation, break the paragraph. Or, if you want a reveal to land with impact, isolate it.

Actors instinctively understand these cues, and directors read them as beat changes. Breaks are your invisible choreography.

Examples of Real Monologues and Why they Work

Studying great monologues is one of the fastest ways to understand how they function. Below are several iconic examples from film and television. They’re moments where a character takes the floor, the world narrows around them, and the scene fundamentally changes because of what they reveal.

None of these monologues are iconic because they’re long but because they’re honest, risky, and story-shifting.

Good Will Hunting (1997)

Sean gently confronts Will in his office, pushing past Will’s defenses until Will is forced to face the trauma he’s buried for years.

So why does this monologue work so well? It peels back Will’s emotional armor. Notice how Sean doesn’t lecture him but challenges a belief that he climbs onto, and every repetition he makes escalates the emotional stakes.

The speech changes the power dynamic between the two characters, and we see Will finally collapse into vulnerability.

The moment isn’t exposition but an emotional action which triggers a breakthrough for Will.

Network (1976)

News anchor Howard Beale erupts on live television, unleashing a furious monologue about societal decay and public apathy.

This is a standout example of a monologue because it transforms a quiet, failing news broadcast into a cultural earthquake, expressing the character’s internal unraveling through a public scream of truth.

It also directly affects the plot in that the network exploits the outburst, setting the story in motion. A rallying cry into the universe and in the cultural memory of viewers.

Breaking Bad (2008-2013)

Skyler fears Walter is in danger. But Walter counters her concern with a monologue that reveals just how far he’s transformed.

It’s such a powerful moment in the series, exposing Walter’s escalating hubris and moral decay. The audience’s understanding of him as a protagonist is also reframed as he’s empowered.

The monologue shifts Skyler’s perspective, adding fear, distance, and new tension to their dynamic. Most of all, it’s a moment of self-revelation as Walter admits to both himself and to us who he believes he is now.

The Social Network (2010)

Mark delivers a cold, razor-sharp explanation of why the lawsuit against him doesn’t matter to him.

The monologue reveals character through detachment rather than emotion, which exposes Mark’s values of productivity, superiority and contempt for social structures.

It completely reframes the courtroom scene, showing that Mark already lives in a world above the conflict.

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001)

In this famous scene, Frodo laments receiving the Ring. Gandalf responds with a reassuring monologue about fate, burden, and choice.

Here, Gandalf provides emotional grounding and moral clarity, shifting Frodo’s perspective from despair to acceptance. It’s a powerful moment where Gandalf articulates the theme of the entire trilogy in merely a few lines.

Scandal (2012-2018)

Throughout the series, Olivia delivers surgical monologues where she asserts power, truth, and strategy, often flipping the room!

Olivia often uses monologues as weapons, each one changing the landscape of the scene. They show how language can reinforce authority and how powerful words can be.

And for more scripted versions of great monologues, check out the Writers Guild Foundation’s Guide right here.

FAQs

Longer than you think, shorter than you want, and exactly as long as it needs to be.

As a rule of thumb: Half a page is common. A full page is rare but acceptable if earned. Anything beyond that better be scene-defining or you risk alienating your reader. Remember, the length is justified by the emotional or narrative impact.

Nope. Monologues follow standard dialogue formatting:

1. CHARACTER NAME

2. Parenthetical (optional)

3. Dialogue block

Break up long monologues into smaller chunks for readability but keep formatting standard.

A monologue is spoken to others, a soliloquy is spoken to self, and a voiceover is spoken to the audience (or over the scene).

Soliloquies reveal internal thought while monologues reveal intention through speech.

Think of the iconic moments:

– Emotional confessions

– Climactic confrontations

– Rousing speeches

– Quiet, devastating admissions

Most memorable monologues aren’t famous because they’re long but because they’re honest.

Conclusion

Monologues are one of the boldest choices a screenwriter can make. They slow the story down so a character can finally speak their truth—not in fragments, not in clever one-liners, but in a moment that demands attention. That’s why they’re risky: the longer a character talks, the more exposed they become… and the more exposed you, the writer, become as well.

A monologue is a contract with the audience. You’re saying: “This is important. Stay with me.” If the moment isn’t justified, the audience breaks that contract. They drift. They disengage. They stop trusting that your story knows where it’s going.

But when the monologue is earned and when it’s the culmination of pressure, secrecy, conflict, desire, fear, or revelation, that’s when the magic happens. Suddenly the scene sharpens. Relationships shift. Stakes rise. The character stands in the center of the narrative like a lighthouse cutting through fog.

A great monologue distils the story’s emotional core into a single voice. It’s the moment the character steps fully into themselves and insists they be heard whether they’re confessing, confronting, persuading, unraveling, or finally telling the truth they’ve avoided the entire film.

Focus on your story, not your formatting.

Let Celtx’s Script Editor automatically apply all industry rules while you focus on the story.

Up Next:

10 Tips for Writing Dialogue That Feels Real

Monologues give characters the spotlight, but dialogue drives every scene. This guide shows how to craft conversations that feel natural, reveal character, and keep your story moving.