This is a guest article written by script reader David Schwartz

Every aspiring screenwriter makes mistakes—it’s part of the learning process. As a professional script reader, I’ve come across thousands of scripts, and honestly, most of them needed some work done before they can get their projects in front of a major studio or producer.

When I look at scripts, I base my feedback on my screenwriting knowledge and experience from what professionals have told me about my scripts. Believe me, I’ve made a few mistakes too! Believe it or not, everyone makes errors in their scripts and even films produced today aren’t perfect. The good news? Most of these mistakes are easily fixable.

Below, we’ll break down ten of the biggest screenwriting missteps and how you can avoid them.

Table of Contents:

- Mistake #1: Formatting Errors

- Mistake #2: Lack of Character Development

- Mistake #3: When Structure Falls Apart

- Mistake #4: Scene Length

- Mistake #5: Overuse of Parentheticals

- Mistake #6: Scenes Without Conflict or Purpose

- Mistake #7: Overusing Microdirection

- Mistake #8: On-the-Nose Dialogue

- Mistake #9: Different Movie, Same Premise

- Mistake #10: Lack of World Building

- Conclusion

Mistake #1: Formatting Errors

One of the biggest mistakes beginners make is formatting. If you’re using screenwriting software like Celtx, formatting is done for you, making it much easier. However, not everyone has experience with screenwriting software, and that’s where common mistakes creep in.

Common Formatting Mistakes:

- Forgetting (CONT’D) on continued dialogue – When a character speaks, then there’s an action line, and they speak again, some writers forget to include (CONT’D) next to the character’s name. With Celtx, this is automated, so you don’t have to worry about manually adding it.

- Mixing up (O.C) and (O.S) – (O.C) (Off Camera) means the character is in the scene but not visible, while (O.S) (Off Screen) means the character is speaking but is not physically in the room. A common mistake is using (O.C) when the action line actually shows the character entering the room.

Example of Correct (O.C) Usage:

INT. HOTEL SUITE – NIGHT

Jarrod adjusts his tie in the mirror, checking out his sexy reflection.

CAROLYN (O.C)

Ready to go?

Jarrod turns to her and admires her beautiful sparkling gown.

In this example, Carolyn is in the scene, but the focus is on Jarrod. Once he turns to face her, we imagine the camera cutting to Carolyn in the room.

How to Fix It:

- Use screenwriting software like Celtx to automatically format dialogue and scene elements correctly.

- Double-check (O.C) and (O.S) in context – if the character is about to enter the room, (O.S) is likely the correct choice.

- Avoid unnecessary transitions and camera directions – Beginners tend to overuse “CUT TO:” or specific camera angles like “ECU on…” Unless you’re directing the script, keep it in spec format. The only transitions you need are “FADE IN” at the start and “FADE OUT” at the end.

This keeps your script clean, professional, and easy to read—letting the story take center stage.

Mistake #2: Lack of Character Development

Believe it or not, most movies have character development—because without it, what’s the point? I’ve read scripts where the protagonist stays the same from beginning to end, and by the time I finished, I questioned why I was rooting for them in the first place.

Common Issue:

- Flat protagonists – If your main character doesn’t change or grow, the story can feel stagnant.

Some characters, like James Bond, don’t need significant development. He’s the same suave secret agent in every film—battling bad guys, drinking martinis, and winning over beautiful women. But unless you’re writing the next Bond movie, your protagonist should evolve throughout their journey.

How to Fix It:

- Give your character an arc – Whether they grow, learn, or change, their journey should have impact.

- Ask yourself: What’s different by the end? – If your protagonist is the same person on page one and page 120, something’s missing.

- Look at why audiences root for them – Are they compelling because they evolve, or just because the plot says they should be?

Character growth keeps your audience invested—make sure your protagonist earns it.

Mistake #3: When Structure Falls Apart

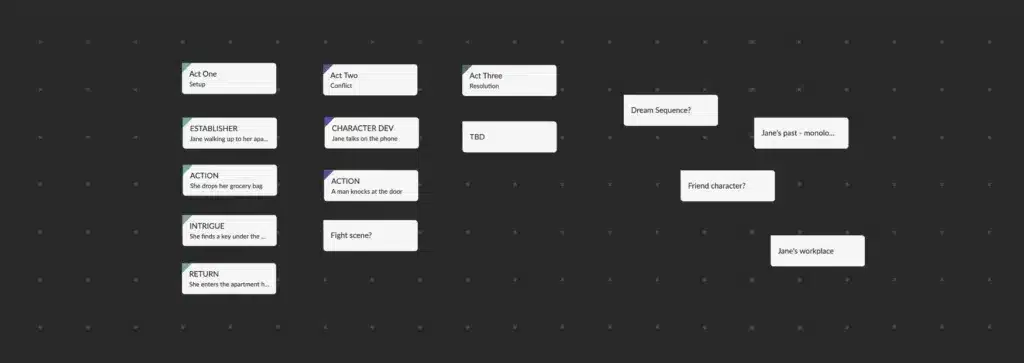

Before you start writing, your script needs structure—I can’t stress this enough. Having a beat sheet before you dive into your first draft can make all the difference.

Common Issue:

- Acts that are uneven or misplaced – I’ve read scripts where the inciting incident happens right away, leaving a rushed 15-page first act, followed by a 60-page second act and a 50-page third act… Please, just rework your script.

On the flip side, I’ve also seen scripts where the inciting incident doesn’t happen until page 30—which is way too late. If we don’t know who your protagonist is before the story kicks into gear, there’s no reason to root for them.

How to Fix It:

- Introduce your protagonist before the inciting incident – Give us enough time to know who they are before their world changes.

- Find the right pacing – The inciting incident should typically land around page 13 (give or take).

- Weave in backstory naturally – You don’t need to dump everything at the start. Sprinkle details throughout the script so we learn more about your character as they grow.

A solid structure keeps your script engaging—so take the time to get it right.

Mistake #4: Scene Length

When writing a scene, it’s important to drive the plot forward and get the point across. Think of it like a party: arrive late and leave early.

Common Issue:

- Scenes that are either too long or too short can disrupt the flow of a script.

I once read a script at Austin Film Festival (AFF) where a single scene stretched 15 pages, with two characters taking turns reading from a book. Was there conflict? No. Did it move the story along? Not really. On the flip side, if a script has multiple back-to-back short scenes, it can feel choppy and disjointed—unless it’s a montage.

How to Fix It:

Most scenes should be between 2-3 pages to maintain pacing and engagement. If a scene stretches too long, ask:

✔ Is every moment necessary?

✔ Is there conflict or tension?

✔ Does it reveal something new about the character or plot?

If a scene is too short, consider whether it’s providing enough context, buildup, or emotional weight before moving on.

Example of Balanced Scene Length:

- A quick reaction shot or single-line moment may be short, but too many in a row can feel abrupt.

- A high-stakes interrogation might run 5 minutes because the audience needs the full exchange.

Related Reading: Screenplay Format Essentials: How to Professionally Structure Your Script

Mistake #5: Overuse of Parentheticals

Parentheticals can be useful in a script, but overusing them can clutter your dialogue. I’m guilty of doing this too! The key is to use them only when necessary—especially in group conversations where they clarify who a character is speaking to.

Common Mistakes:

Some writers rely too heavily on parentheticals, adding them even when the context already makes things clear.

If there’s a group of characters conversing, then make sure to use the parentheticals to show us who the character is talking to.

Example:

JONI

(to Mike)

I heard the shrimp is fantastic here!

MIKE

Oh…about that.

JONI

What?

Mike rubs the back of his neck.

MIKE

I’m allergic.

The waiter approaches the table with a pen in hand.

WAITER

Ready?

JONI

(to Mike)

Want more time?

Mike nods.

How to Fix It:

Use parentheticals only when the dialogue might be unclear without them. In the example, we don’t need a parenthetical for the waiter—it’s already clear he’s speaking to Joni and Mike. However, Joni’s parenthetical (“to Mike”) helps clarify her line, since there could be other people at the table.

A good rule of thumb: If the reader can easily tell who’s speaking to whom through context and action, skip the parenthetical!

Mistake #6: Scenes Without Conflict or Purpose

I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve seen scenes that have no conflict or anything to do with the plot. Picture this: A guy wakes up, turns off his alarm clock, gets out of bed, stretches, drags himself to the restroom, takes a shower, gets dressed, brushes his teeth, gargles mouthwash, exits the bathroom, and leaves his bedroom. What’s wrong with this scene? It’s boring. There’s no conflict. Everyone does that (well, except the mouthwash part, maybe). But you get the idea—each scene has to move the plot forward and engage the audience.

Common Issue:

- Scenes with no conflict or purpose – If a scene doesn’t have conflict or serve the plot, it’ll slow down the pacing and bore your audience.

Very rarely are films produced with two-minute scenes that don’t contain conflict or drive the plot forward, such as the boat scene from Willy Wonka.

Let’s analyze the scene for a moment. Is it trippy? Yes. Is there conflict? No. Does it drive the plot forward? No. Is it mentioned ever again? No. Do we leave the scene questioning what we just saw? Some might enjoy the scene because of how trippy it was, and it adds to the unease you’re intended to feel – but outside of Willy Wonka, this scene probably doesn’t work.

How to Fix It:

Focus on Conflict: Every scene should have some form of conflict—whether internal or external. Conflict keeps things interesting and propels the story forward.

Ask These Questions When Crafting Your Scene:

- Whose scene is it?

- What do they want?

- What stands in their way?

- How do they feel?

Is the Scene Driving the Plot? If the scene doesn’t help move the story forward, consider removing it or revising it to introduce conflict.

Remember: If a scene doesn’t contain conflict or drive the plot forward, it’s not just pointless—it’s a missed opportunity. Don’t waste time on filler; make sure every moment counts!

Need help refining dialogue? Celtx’s screenwriting software keeps your script formatting seamless, so you can focus on writing natural, compelling conversations.

Mistake #7: Overusing Microdirection

Microdirection is when you get too specific on the page, telling an actor exactly how to perform. It’s like writing, “A teardrop rolls down her cheek.” But that’s not really your job as a screenwriter—it’s the director’s job to interpret the script and guide the actors.

Common Issue:

Excessive microdirection – Directing the actor’s emotions or movements too specifically can feel constraining and often isn’t necessary. The director is there to bring the scene to life with the right performance, so leave room for interpretation.

Imagine telling an actor, “Before you say your line, I want a teardrop to roll down your cheek.” Sounds strange, right? It takes away the actor’s ability to naturally express emotion based on the situation. Your job is to create a scene that allows that to happen organically.

How to Fix It:

- Focus on the Emotion: Write the character’s emotional intent rather than the exact action. Let the director and actors figure out how to bring those emotions to life in the most natural way.

- Example of Good Writing:

Instead of saying “A teardrop rolls down her cheek,” try “Her voice cracks as she speaks, the weight of the moment pressing on her.” - Don’t Overdo It: A line or two of microdirection might work when absolutely necessary, but don’t make it a habit. The more room you leave for creativity, the better the performance will be.

Pro Tip: Trust the director and actors to understand the emotional beats you’re writing. Give them space to do what they do best.

Mistake #8: On-the-Nose Dialogue

On-the-nose dialogue is when a character states exactly what they’re thinking or reveals something overly obvious. This kind of dialogue can come off as lazy or unrealistic, often pulling audiences out of the story.

Common Issue:

Characters speaking their inner thoughts out loud – For instance, a villain explaining their evil plan in detail might feel unnatural or too convenient. It can work once in a while, but it loses its impact if used too often.

Remember the iconic scene in The Lion King when Scar confesses his plan out loud? It works in that moment, but if every character was constantly revealing their plans, it would become predictable and boring.

How to Fix It:

- Use Subtext: Instead of saying exactly what a character means, let the audience read between the lines. This will create a more engaging and layered conversation.

- Example of Good Writing: Instead of saying “I’m going to destroy you,” consider showing it through actions, tone, and the stakes in the scene. Let the characters’ behavior and the situation speak for itself.

Pro Tip: Dialogue should feel natural, and often, less is more. Let the audience fill in the gaps.

Mistake #9: Different Movie, Same Premise

Ever watch a film and think, “Haven’t I seen this before?”

Hollywood loves recycling ideas, and sometimes, it feels like movies are just reboots or rehashes of older stories. But as a writer, your goal is to create something fresh and unique, even if you’re playing with familiar tropes.

Common Issue:

Unoriginal concepts – If you find yourself thinking your story has been done before, it probably has. This happens a lot with war films, for example. Even in my own experience, I had to rewrite my first feature, After Ever After, multiple times to make sure it stood out from similar stories, like Shrek.

It’s important to be aware of what’s been done and make sure you’re adding something new, even if you’re working with familiar ideas.

How to Fix It:

- Make It Your Own: Take classic tropes and put your unique spin on them. In After Ever After, I turned the classic princess-in-distress trope on its head by making the prince the one who needed saving instead of the princess.

- Look for Fresh Angles: Ask yourself, what can I do differently? What will make my version of this story stand out from the rest?

Pro Tip: If your script reminds you of something else, it’s time to rethink it. Rewriting can feel tough, but it’s often the best way to find your story’s true identity.

You might find this helpful: How to Rewrite a Script: A Hands-On Master Checklist || Script Reader Pro

Mistake #10: Lack of World Building

Whether you’re writing fantasy, sci-fi, or even a grounded drama, world-building is essential. It’s not enough for your characters to simply exist in a setting; you need to bring that world to life and make it feel real.

Common Issue:

Weak or vague settings – Your audience needs to be able to visualize the world your characters are living in. This doesn’t mean you need to describe every detail, but a few key features can help immerse your audience.

How to Fix It:

- Paint a Picture: Use visual cues to show the world. For example, if you’re writing a bar scene, make sure it feels unique and fits the tone of the story. Is it a gritty dive bar or a sleek, modern cocktail lounge?

- Keep It Brief but Impactful: Use 2-3 key details to set the scene. Too much description can bog down the pacing, but a few strong details can create a vivid, memorable setting.

Pro Tip: Find a visual reference (like a Google image search) and use that as inspiration for how you describe the scene. Just make sure to keep it concise and purposeful.

Conclusion: Keep Learning and Stay Kind to Yourself

At the end of the day, screenwriting is a journey of growth and learning. We all make mistakes, even when we’ve been doing this for years. The key is to learn from them and keep improving. I still find myself making some of these mistakes in my own work, but it’s all part of the process.

Pro Tip: Be kind to yourself. Mistakes are just part of the creative process. With hard work and persistence, you’ll continue to grow as a writer.

Celtx can help you focus on the craft of storytelling while taking care of formatting.

Ready to bring your script to life?

There’s always more to learn! Try these articles next:

- 10 Tips for Writing Dialogue That Feels Real

- Film School Not Required: Best Online Screenwriting Classes and Resources

- What is a Slugline? Definition, Examples, and Tips