Let’s face it. Most screenwriting advice sounds like this:

“Show, don’t tell.”

“Make it visual.”

“Let the audience do the work.”

All true, yes. But they’re all maddeningly vague. So, let’s make it concrete.

Imagine a character trying to explain grief or corruption or love, or even why they’re about to betray their best friend. If they just say it, the line lands flat. But if they monologue, we roll our eyes. And if they stay silent, the audience may miss it entirely. This is where analogy earns its keep.

Analogy is one of the most powerful, and honestly underused tools in a screenwriter’s toolbox. It clarifies complex ideas, deepens character voice, sharpens dialogue, and sneaks subtext past the audience.

In today’s blog, we’ll break down what analogy actually is, how it differs from metaphor and simile, why it works so well on screen, and how to use it without sounding like a dodgy fortune cookie from the Chinese takeaway.

What Is Analogy?

An analogy explains one thing by comparing it to another thing that’s more familiar, concrete, or easily visualized.

In essence, it’s ‘this complicated idea is like that simple thing.’ That’s it.

An analogy is functional and exists to clarify and to bridge the gap between something abstract (emotion, morality, systems, psychology) and something concrete (objects, actions, everyday experiences).

For us screenwriters, this matters. Why? Well, because film is visual, dialogue is limited, and audiences are smart, but can become easily distracted.

So, let’s dive a little deeper…

Analogy vs. Metaphor vs. Simile

The literary device terms analogy, metaphor, and simile are often used interchangeably, which is understandable. But the distinctions matter if you’re writing dialogue that needs to sound human instead of poetic-on-purpose.

Here they are one by one:

Metaphor

A metaphor states that one thing is another:

“Grief is locked in a room.”

Simile

A simile compares using like or as.

“Grief is like a locked room.”

Analogy

An analogy explains the comparison, often extending it.

“Grief is like a locked room. You know something’s inside, but you don’t have the key, and everyone else keeps asking why you’re still standing in the hallway.”

That last part is the giveaway. An analogy doesn’t stop at the comparison. It uses the comparison to do work: clarify, persuade, reveal character, or reframe the situation.

Think of metaphors and similes as tools of poetry and analogy as a tool of thinking.

Analogy Examples in Dialogue

Great dialogue analogies don’t announce themselves but sound like something a real person would say when they’re trying, and maybe failing, to explain themselves. Here are a few famous examples that work because they clarify both emotion and character:

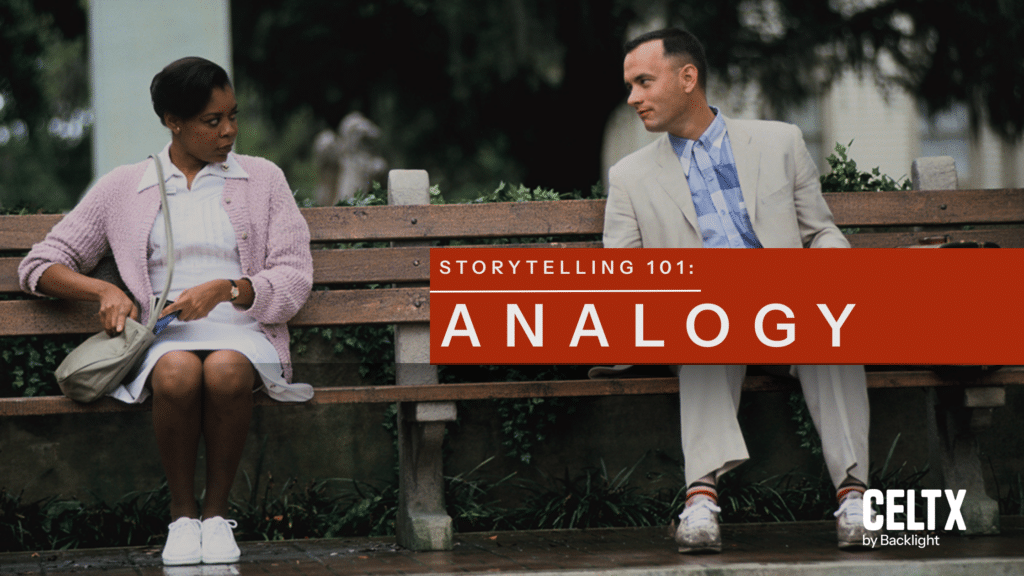

“Life is like a box of chocolates. You never know what you’re gonna get.” – Forrest Gump (1994) Paramount Pictures

On the surface, this is simple and almost naïve. But that’s the point; the analogy reflects Forrest’s worldview: life isn’t cruel or random, it’s just unknowable. He accepts this.

“You know how you get to Carnegie Hall, don’t you? Practice.” – Inglourious Basterds (2009) Universal Pictures

This is a functional analogy that reframes talent as effort. It’s not flashy but it lands because it uses a shared cultural reference to make an argument quickly.

“It’s like trying to grab smoke. Like trying to grab smoke with your bare hands.” – Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004) Warner Bros. Pictures

This quote, found in many films and literary works, is great because it’s tactile. You can feel the frustration in the analogy that does emotional labor in just a few words.

The lesson from all these examples is that great analogies in dialogue doesn’t sound like writing but like someone reaching for language in real time.

And we can also learn a lot from Aaron Sorkin, the master of dialogue. Voltamps Reactive explains exactly what we can take from Sorkin’s work here.

Analogy Examples in Film and TV

Okay, so we’ve spoken a lot about spoken analogy in dialogue, but let’s not limit ourselves. Film, after all, is a visual medium, and some of the strongest analogies never use words at all.

Juxtaposition is visual analogy’s best friend.

Cut from:

- A politician shaking hands to a meat grinder

- A happy family dinner to soldiers eating rations in silence

- A child learning to ride a bike to a criminal pulling off their first job

You’re not saying these things are the same and instead are inviting the audience to connect them.

Let me explain:

In The Godfather we cut between a baptism and a series of murders. The analogy is brutal and elegant: spiritual rebirth versus moral annihilation with no dialogue required.

Visual analogies trust the audience and create meaning through contrast, rhythm, and implication which is exactly what good screenwriting should do.

How to Use Analogy in Dialogue

Now it’s time to get practical. Here’s a simple, repeatable process for crafting effective analogies that don’t feel forced.

How to use analogy in dialogue

- Identify the Abstract

Start by naming the thing you’re trying to communicate. Common abstract targets include:

– Grief

– Guilt

– Power

– Love

– Corruption

– Fear

– Addiction

– Moral compromise

If you can’t name it, you can’t clarify it. - Find the Concrete

Now ask: what everyday thing feels like this? Not what sounds poetic, but what feels accurate.

Good sources for everyday things could be:

– Manual labor

– The weather

– Food

– Sports

– Childhood experiences

– Mundane routines

For example:

“Forgiveness is like trying to put a broken plate back together. Even if it holds, you still know where it cracked.”

This analogy is concrete, visual, and most importantly, human. - Ensure Character Voice

Most analogies lie in character voice. They must fit:

– The character’s background

– Their intelligence

– Their emotional state

– Their profession

– Their cultural references

A dockworker and a philosophy professor won’t reach for the same comparisons. And if a teenager starts talking like Rilke, the audience smells the writer immediately. So, ask yourself:

– Would this character think this way?

– Would they use this object?

– Would they explain it this clearly?

Sometimes the best analogies are clumsy, incomplete, and slightly off. But hey, that’s realism, and we’re here for it!

Make sure to test the analogy to make sure the phrasing fits the character’s background and intelligence level.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Even the strongest writers can fall into traps, so it’s always better to be aware of them where you can.

1. Using Cliches

If the audience finishes the analogy before the character does, it’s dead. Such as:

“Like flogging a dead horse.”

“That’s a ticking time bomb.”

“Talking to you feels like walking on eggshells.”

Cliches shortcut thinking and take the audience out of the story.

2. Over-Explaining

Trust the analogy; you don’t need to unpack every suitcase. Try to avoid analogies like this:

“It’s like drowning, you know, because drowning is when you can’t breathe and panic sets in, and that’s how I feel emotionally.”

We get it. Move on!

3. Sounding Too Clever

If the analogy exists to just impress the audience rather than serve the story, it definitely shows. Remember, analogy is a delivery system, not a spotlight!

FAQs About Analogy

Let’s do a quick recap:

– A metaphor states a comparison

– A simile compares using like or as

– An analogy explains or extends the comparison to clarify meaning

All are figurative language, but analogy is simply the most useful for storytelling.

Figurative language includes any expression that goes beyond literal meaning to create imagery or association: metaphors, similes, analogies, symbols, and personification.

In screenwriting, figurative language works best when it serves character and clarity. It’s not just decoration.

For more on figurative language, check out this awesome article from The Poetry Foundation.

A few common categories:

– Cause and effect

– Part to whole

– Function-based

– Symbolic

– Visual

– Emotional

– Situational

– Moral

– Historical

– Verbal

You don’t need to memorize these. Just know that analogy is flexible and adapts to what the scene needs.

A verbal analogy is expressed entirely through language (usually dialogue), as opposed to visual analogy created through editing or imagery. Most dialogue analogies fall into this category, and they live or die by character voice.

Conclusion

Analogy is not about being clever. It’s about being clear, how characters explain what they don’t fully understand, how writers smuggle theme into dialogue, and how abstract ideas become cinematic.

If theme is what your story means, analogy is often how the audience gets it without feeling like they were taught a lesson. So, the next time a scene feels flat, ask yourself:

- What’s the abstract idea here?

- What’s the concrete experience that matches it?

- And would this character actually say it that way?

Do that, and your dialogue won’t just sound smarter but truer.

Focus on your story, not your formatting.

Let Celtx’s Script Editor automatically apply all industry rules while you focus on the story.

Up Next:

Understanding Metaphor: A Screenwriter’s Guide

Analogies often build on metaphor and comparison. This guide breaks down what metaphors are, how they differ from analogies, and how to use them clearly in your writing.