![screenwriting wow: how to create a plot outline [with the help of beat sheet]

celtx logo is at the bottom right.](https://m8p8v8q3.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/screenplay-plot-outline-1024x576.png)

Every story you love, every movie that wrecked you emotionally, every novel you couldn’t put down, has one thing in common: structure. Not flashy dialogue or quirky characters. Structure. Yep, we’re talking about plot outlines. Yes, you need one.

And before you panic, no, structure doesn’t mean formulaic, boring, or creatively suffocating. It means your story has bones, can stand up and move. It can also punch the audience in the feels instead of collapsing into a puddle of cool ideas that never quite land. That’s where the beat sheet comes in.

If you’ve ever started a script strong and completely lost the plot halfway through, written beautiful scenes that don’t connect or hit the midpoint and thought “wait, what is this story actually about?” then you don’t have a talent problem. You have an outlining problem.

That’s where the plot outline comes in. In today’s blog, we’re going to break down what a plot outline really is, how techniques like beat sheets provide the logic, and how to create a roadmap that acts like your story’s DNA — guiding everything without killing your creative soul.

Let’s get into it.

Table of Contents

- What Is a Plot Outline in Screenwriting?

- Why a Plot Outline is Essential for Your Script

- Top Plot Outline Techniques: From Beat Sheets to Timelines

- Structural Frameworks: The Roadmap for Your Plot Outline

- How to Create a Plot Outline (That Actually Works)

- Alternative Frameworks for your Plot Outline

- Common Plot Outlining Mistakes to Avoid

- Using Celtx to Visualize Your Plot Outline

- FAQ About Plot Outlines

- Conclusion

What Is a Plot Outline in Screenwriting?

A plot outline is the underlying structure of your story: the sequence of major events (or beats) that cause change.

Think of it like DNA. You don’t see it on the surface, but it determines how the story grows. And if it’s broken, the whole organism struggles.

A good plot outline from the opening scene to the final image answers three questions:

- What happens?

- Why does it happen?

- How does it change the protagonist?

If your outline can’t answer those, the script will eventually expose the cracks.

Why a Plot Outline is Essential for Your Script

Screenwriting is ruthless. You don’t have the luxury of 600+ pages to wander. Instead, you have around 110 pages to introduce your world, hook an audience, break a character, then rebuild them, and finally, to stick the landing.

Sounds a lot, right? Well, a plot outline keeps you honest and on track. It ensures:

- Every major moment earns its place

- The story escalates instead of looping

- Emotional turns align with plot turns

Without a beat sheet, writers often fall into one of three traps:

- Vibes over story with great scenes but little to no momentum

- Act Two soup where stuff happens but nothing actually changes

- Last-minute endings where the climax feels rushed or unearned

A beat sheet is the antidote to the poison that is lack of structure!

Top Plot Outline Techniques: From Beat Sheets to Timelines

Before we dive into the milestones, let’s clear up a common confusion: The plot outline is the house; the beat sheet and timeline are the blueprints.

A beat sheet defines what happens and why (story logic), whereas a timeline details when it happens (pacing). To build a professional outline, you eventually need both.

So, what makes strong story structure? Check out Story Structure 101 from Reedsy below:

Structural Frameworks: The Roadmap for Your Plot Outline

To build a professional plot outline, you need a framework. These models act as the “gravity” of your story, ensuring your scenes are moving toward a meaningful conclusion. While there are many theories, three stand out as the most effective for screenwriters.

1. The 15 Essential Story Beats (Industry Standard)

There are many models for structuring a plot outline, but most successful scripts hit 15 essential narrative pressure points (made popular by Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat!). Think of these as narrative pressure points that ensure your story never loses momentum.

- Opening Image (a snapshot of the protagonist’s world before change)

- Theme Stated (a hint at what the story is really about)

- Set-Up (characters, stakes, flaws, and the status quo)

- Catalyst/Inciting Incident (the event that disrupts everything)

- Debate (the protagonist resists change, as humans do)

- Break Into Act II (a choice that launches the journey)

- B-Story (subplots, relationships, and emotional reinforcement)

- Fun and Games (the promise of the premise)

- Midpoint (a major reversal or revelation: false victory or false defeat)

- Bad Guys Close In (external pressure + internal conflict)

- All is Lost (the lowest point)

- Dark Night of the Soul (reflection and realization)

- Break into Act III (the final plan or decision)

- Finale (the climax where change is tested)

- Final Image (the world after transformation)

It’s a long list, but don’t worry about memorizing it. Instead, use this list to check off each beat, and diagnose problems in your potential plot.

Want a deep dive into these 15 points? Check out our Ultimate Guide to Beat Sheets

2. The Hero’s Journey (The Monomyth)

If you are writing a “quest” or an epic adventure, Campbell’s Hero’s Journey is the classic plot outline method. It focuses on the protagonist’s departure from the “Ordinary World” into the “Special World.”

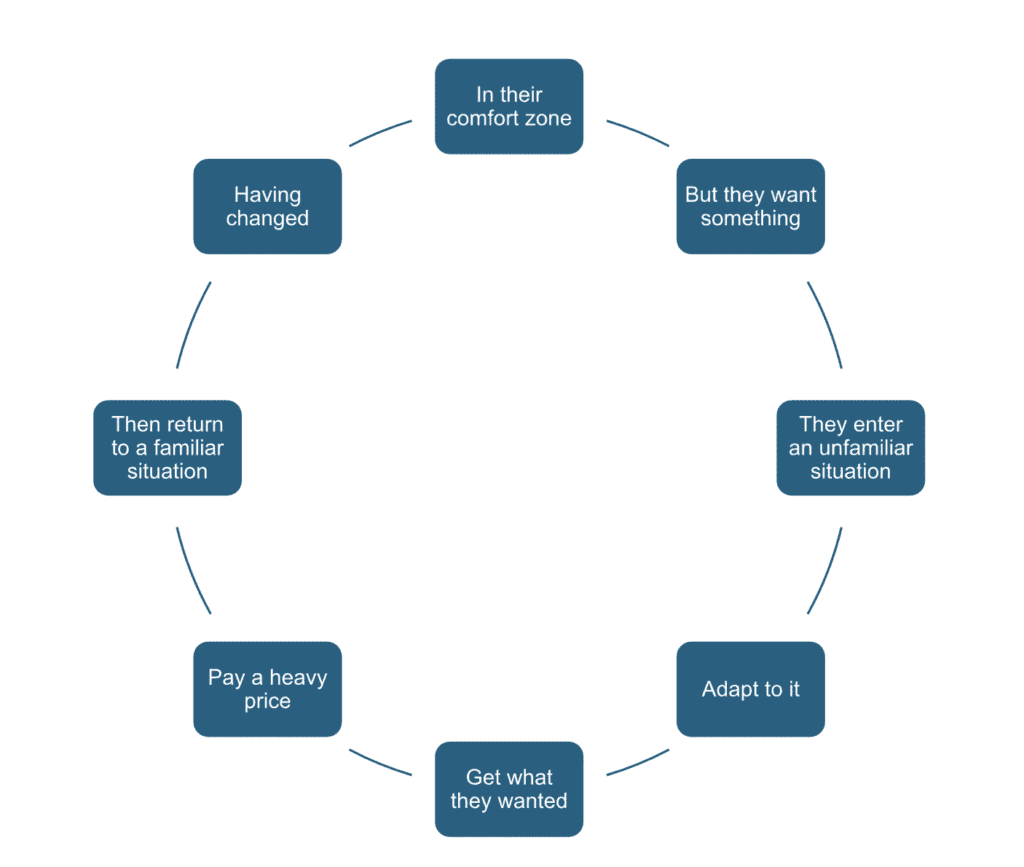

3. Dan Harmon’s Story Circle

For character-driven plot outlines, the Story Circle focuses on the internal “need” of the protagonist. It emphasizes that stories are cyclic; the character returns to their starting point but has been fundamentally changed by the journey.

How to Create a Plot Outline (That Actually Works)

Now, let’s get practical. Here’s our four-step guide to creating an effective plot outline using old fashioned index cards:

How to create a plot outline

- Identify Key Beats

Before you outline anything, lock in the non-negotiable tentpoles of your plot:

– The Inciting Incident (what forces change?)

– Midpoint (what fundamentally shifts the game?)

– Climax (where is the ultimate confrontation or choice?)

If these three plot points aren’t clear, the rest of the outline will wobble. Ask yourself:

– What decision pulls the protagonist into the story?

– What moment makes turning back impossible?

– What final action proves they’ve changed?

Remember, these beats aren’t optional. They’re the integral structural gravity wells of your story. - Map Your Scenes (One Card = One Sequence)

This is where the magic happens. A great plot outline is built one scene at a time. Whether you’re using physical index cards or digital tools like Celtx, the rule is sacred: one card = one scene. This allows you to move the ‘bones’ of your story around until the flow is perfect.

- Use the Timeline to Check Flow and Pacing

Once your cards exist, lay them out in order and look for the following:

– Long stretches without escalation

– Too many setup scenes in a row

– A midpoint that doesn’t actually change anything

Physically seeing the story helps you notice problems your brain politely ignored while writing prose. If Act Two feels bloated, it usually is. - Incorporate Subplots (Without Letting Them Hijack the Story)

Subplots are powerful, but only when they serve the main story.

Color-code or tag subplot cards and ask yourself:

– Do they intersect with major beats?

– Do they reinforce the theme?

– Do they change the protagonist?

If a subplot could be removed without affecting the main arc, it’s not a subplot but a distraction.

Common Plot Outlining Mistakes to Avoid

So, we’ve focused so much on the dos when it comes to beat sheets and outlining, but what about the don’ts. Let’s see what you’d be wise to avoid doing when structuring your story.

Skipping Beats

You may think skipping beats makes your story sophisticated. Well, it has the opposite effect: it makes it confusing. Audiences feel missing beats instinctively:

- The inciting incident feels weak

- The midpoint feels flat

- The climax feels unearned

If something feels ‘off,’ check the structure before rewriting dialogue for the fifth time.

Over-Explaining Beats

On the flip side, don’t write a novel on each card. A beat should be clear, not verbose.

Let’s take a look at a bad example of a beat index card.

“Protagonist discusses childhood trauma symbolizes fear of commitment while foreshadowing later conflict.”

Let’s improve it:

“Protagonist refuses to commit to the relationship.”

Here, clarity beats cleverness. But don’t just take our word for it. Let’s hear from a professional script reader on potential fixes you should be looking out for (and making!) in your next script. Check out this article from Industrial Scripts: 49 Fixable Reasons A Screenplay Reader Passed on Your Project.

Using Celtx to Visualize Your Plot Outline

If index cards scattered across your desk sound disastrous, Celtx is built for this stage of story development. The Celtx Story Outline and Beat Board tools let you mirror the classic outlining process with digital flexibility… Instead of rewriting your entire plot outline every time a scene changes, Celtx lets your story’s DNA evolve organically.

What makes Celtx especially useful:

- Visual timelines help you see act breaks, pacing, and story flow at a glance

- Color-coded beats make it easy to track subplots alongside the main story

- Direct integration with your script, so your outline doesn’t live in a separate universe

Instead of rewriting outlines every time something changes (because trust me, it will), Celtx lets your beat sheet evolve organically, keeping your story’s DNA intact as you draft and revise.

In short: it’s index cards, a timeline, and a screenwriting workspace rolled into one.

FAQ About Plot Outlines

Plot holes usually come from missing cause-and-effect. A thorough outline forces you to answer:

– Why does this happen now?

– What causes the next event?

If you can trace a clean line from beat to beat, plot holes struggle to survive.

You can, and many writers do. But hear me out. Even ‘discovery writers’ benefit from post-draft outlining. Reverse engineering a beat sheet from a draft reveals where momentum dies, where stakes vanish, and where character arcs stall.

Ideally, before—but “ideally” doesn’t mean “mandatory.”

Creating a plot outline before writing helps you identify weak story logic early, avoid major rewrites later, and to write with confidence instead of guesswork.

That said, outlining after a rough draft (often called a reverse outline) can be just as powerful. By mapping your existing scenes into an outline format (whether that be a beat sheet or on index cards), you can see where structure breaks down, which beats are missing, and where the story loses momentum.

Conclusion

Here’s the truth: structure doesn’t limit creativity; it protects it. By taking the time to build a robust plot outline, you give yourself the freedom to take risks with your characters and dialogue, knowing that the “engine” of your story is sound.

A solid outline gives you the confidence to draft without fear, makes the revision process surgical instead of overwhelming, and ensures that your ending feels earned. Think of your outline as the quiet force under the hood—the audience never sees it, but they certainly feel it when it’s missing.

Grab your index cards (physical or digital), map your milestones, and build a story that has the strength to stand up and move.

Focus on your story, not your formatting.

Let Celtx’s Script Editor automatically apply all industry rules while you focus on the story.

Up Next:

Turning Your Outline Into a Finished Script

You’ve built the skeleton; now it’s time to add the muscle. Take your structural milestones and learn how to translate them into industry-standard script format with our comprehensive guide on writing your first feature film.