Dream sequences are one of the most tempting tools in a screenwriter’s kit. They promise freedom through surreal images, subtext made literal, symbolism, and liquid mirrors.

But in execution, they’re one of the easiest devices to fumble. A dream can elevate your story into memorable cinema or sink it into eye-rolling cliché. The difference is rarely in the aesthetics, but in the intention.

Dreams are narrative weapons in screenwriting. It’s important to use them with care, purpose, and a little creative brutality. Use them well, and they’ll reward you, but if you treat them like filler or decoration, and you’ll end up with the storytelling equivalent of a lava lamp.

In today’s blog, we’ll walk you through how to write dream sequences that feel meaningful, modern, and anything but tired. We’ll cover purpose, formatting, examples, mistakes, and even some fan favorite existential questions.

Let’s dive in!

What is a Dream Sequence?

A dream sequence is a narrative device that shows the audience a character’s internal experience while they’re unconscious.

It’s an experience can be symbolic, metaphorical, hyper-real, or grounded in the character’s emotional truth. What matters most is that a dream is not bound by the rules of your story world, but it must be anchored to your character’s psychology. Without this anchor, it becomes empty spectacle.

Dreams function as storytelling shortcuts to the subconscious. They can reveal:

- Fears the character can’t articulate

- Desires they’re unwilling to admit

- Secrets they don’t yet consciously know

- Traumas resurfacing

- Foreshadowing (used sparingly, please)

- Guilt, conflict, or inner turmoil

They bypass plot and go straight for essence. But in screenwriting, essence still needs structure.

Breaking Down the Dream Sequence

Like any narrative device, dream sequences should earn their place. Here’s the gold standard test:

Like any narrative device, dream sequences should earn their place. Here’s the gold standard test:

The Purpose Test

Before you write a dream sequence, ask:

1. Does this dream reveal a fear?

The Red Room in Twin Peaks doesn’t tell us what Dale Cooper ate for breakfast; it exposes the terror and mystery baked into the world he’s stepping into.

2. Does this dream reveal a desire?

Think of dreams where characters imagine the life they wish they had, often idealized, often bittersweet, and always telling us more about who they are than any dialogue could.

3. Does this dream reveal a secret?

Not necessarily a plot twist. Sometimes the secret is emotional: guilt they haven’t owned; grief they’re burying; love they can’t say aloud.

If your dream doesn’t pass at least one of these tests, it’s not a dream sequence, but it’s indulgence. Kill it with fire.

Looking for more academic theory? Patricia Kilroe’s article The Dream as Text, The Dream as Narrative is a great resource.

How to Write a Dream Sequence (Formatting Guide)

Dream sequences aren’t just storytelling devices; they have to be readable on the page. Clear formatting helps your director, your editor, your production designer, and your overwhelmed 2nd AD who’s juggling three versions of the call sheet.

There are two common approaches.

Approach One | Standard Scene Headings

You can use your usual scene headings with clarifying cues:

INT. BEDROOM – NIGHT

Sarah tosses in bed, sweating.

INT. WOODED CLEARING – NIGHT (DREAM)

A child’s laughter echoes. The trees breathe in and out.

This method is clean, widely accepted, and doesn’t break the flow of the script. You simply mark the dream with (DREAM) or (DREAM SEQUENCE) at the end of the scene heading. Some writers prefer (FLASH) or (VISION), depending on the tone.

This could also be true if you’re writing flashbacks. Check out our guide How to Write a Flashback: Formatting, Rules, and Tips.

Approach Two | “BEGIN DREAM SEQUENCE” / “END DREAM SEQUENCE”

This can be useful if the sequence is long or frequently intercut with reality.

BEGIN DREAM SEQUENCE

EXT. ABANDONED PLAYGROUND – DAY

The carousel spins on its own. A child-sized shadow darts behind it.

END DREAM SEQUENCE

This approach is ideal when:

- The dream spans multiple locations

- The sequence is symbolic or stylistically distinct

- You want crystal‑clear separation for production

Avoid italics. They’re discouraged in screenplays and hard to read. (More on that in the FAQ.)

Don’t just dream it. Write it.

Sign up for Celtx for free and bring your story to life.

Examples of Dream Sequences

Dream sequences aren’t one-size-fits-all. Let’s look at two iconic, and radically different approaches.

Twin Peaks (1990-1991) | Surrealist Style

David Lynch didn’t invent surrealist dream logic on television, but he’s the reason modern audiences accept it. The Red Room sequence in Twin Peaks is a masterclass in psychological disorientation:

- Reverse speech (creating a tension you feel in your bones)

- Spatial illogic (the Red Room is a place that appears to exist and not exist simultaneously)

- Repetition (“Let’s rock.”)

- Symbolic characters (the Man from Another Place; Laura Palmer’s uncanny smile)

- Movement that feels off (like a body remembering trauma)

The dream doesn’t explain anything outright. It invokes meaning. The audience learns something about Laura’s death, yes, but more importantly, they learn who Cooper is. His intuition and his relationship with the subconscious. His willingness to trust images over answers.

Surrealist dreams work when you want the viewer to experience emotional truth before narrative clarity.

Inception (2010) | The Hyper-Real Dream

Christopher Nolan goes the other way: dreams with rules and physics. Dreams that break physics but only according to other physics.

This approach is ideal if you want:

- High-stakes action in a subconscious world

- A physical manifestation of internal struggle

- Dream logic that escalates plot rather than pausing it

- Clean, trackable layers of reality

In Inception, dreams are essentially story worlds inside story worlds. They’re designed, engineered, interrupted, sabotaged. The “dream within a dream” hierarchy is both an aesthetic trick and structure. Cobb’s guilt over Mal bleeds into the architecture of these dreams, blurring emotional truth with literal danger.

Hyper-real dreams are great for writers who want subconscious conflict to feel immediate, physical, and plot relevant.

The Sopranos (1999-2007) | Symbolic, Character-Driven Dreams

Tony Soprano’s dreams are quieter than Cooper’s and less explosive than Cobb’s — but they’re some of the most psychologically rich dreams on television.

Take the “Kevin Finnerty” arc:

- Tony is alive but dreaming as an HVAC salesman

- His identity is in flux

- He carries someone else’s briefcase

- He’s blocked from entering a house that seems to represent death (or acceptance, or truth)

These dreams aren’t there to be weird. They’re there to map Tony’s internal decay: his guilt, his fear of losing control, his crumbling identity.

Symbolic dreams are perfect when you want slow emotional revelations that mirror a character’s arc over time.

Dream Sequence Common Mistakes

Dream sequences often fail because they’re written as visual experiments instead of story devices. Here’s how to avoid the biggest traps, now with more depth, more nuance, and more screenwriter‑therapy energy.

1. Using Dreams as Emotional Cheat Codes

Dreams aren’t shortcuts for character development. You can’t plug in a dream about a mother’s voice, a childhood bedroom, or a violin playing sadly in the distance and expect the audience to say, “Oh yes, emotional complexity achieved.”

A dream cannot replace real character work. Yes, they can highlight a conflict, but they can’t create one out of thin air.

2. Overloading With Symbolism

A dream sequence with:

- a cracked mirror

- a burning photo

- a wolf at the door

- a faceless child

- and a clock melting over a skull

…isn’t profound. It’s a catalogue of symbols yelling over one another.

Good dream symbolism is simple, recurring, and rooted in the character’s emotional logic. Pick one or two images and let them breathe.

3. Abandoning the Film’s Tone Entirely

Dreams can bend tone, but they shouldn’t completely snap it. A grounded kitchen‑sink drama probably doesn’t need a neon-lit cosmo‑void where the protagonist floats through their childhood trauma monologue.

The more realistic your main story, the more grounded your dream should feel. “Heightened reality” is fine; genre‑breaking whiplash, less so.

4. Making Dreams Too Long

This is a craft note from script readers everywhere: if your dream sequence goes on for seven pages, it better be Inception or a masterpiece.

Most dream sequences should be short, focused, and emotionally efficient. If you find yourself writing a dream that’s the length of a short film, ask if what you’re trying to reveal could be accomplished more directly.

5. Revealing Information the Character Can’t Possibly Know

This is the lazy exposition problem, but let’s push it further: if your character dreams of a villain’s plan they’ve never heard of or sees a real‑world event they weren’t present for, it’s a plot patch rather than a dream.

6. Forgetting the Wake-Up Moment

A dream is only as effective as its re-entry into reality.

If you don’t craft the transition back to the waking world, the audience will feel disoriented in the wrong way: confused rather than intrigued. Awakening moments should have meaning: gasping awake, slow recognition, emotional fallout, tears, relief, denial. The way a character wakes up is characterization.

FAQs About Dream Sequences

Use a clear transition back to reality. You can:

Option 1: Use a direct line in action:

Sarah jolts awake.

Option 2: Insert END DREAM SEQUENCE:

END DREAM SEQUENCE

INT. BEDROOM – NIGHT

Sarah wakes, panting.

Option 3: Use a new scene heading with clarification:

INT. BEDROOM – NIGHT – BACK TO SCENE

Whichever you choose, consistency is key.

Short answer: no. Italics slow down reading. They’re harder to skim (and your script will be skimmed). They don’t format consistently in every script software, and they aren’t standard practice in the industry.

Bold, caps, transitions, or scene heading modifiers already do the job clearly.

The “Who is the dreamer?” theory has been around since the original series but reached full fever pitch with Twin Peaks: The Return. The idea is that the entire story might be a dream of a character we barely (or never) meet; a meta-commentary on identity, trauma, and the act of watching television itself.

But here’s the key: Lynch doesn’t use dreams to negate reality. He uses dreams to deepen it.

Whether Twin Peaks is a dream is the wrong question. The better question is the one the show is actually asking is, “What does it mean to be trapped in a story you can’t escape?” Dream or not, the emotional truth is real.

Yes, with a caveat. Multiple dream sequences only work if:

– Each dream escalates or evolves something

– Each dream has a distinct purpose

– They’re spaced meaningfully through the narrative

– You’re not using them as repetition

Think of Tony Soprano’s dreams: each one adds a new psychological layer. If your dreams are just decorative surrealism sprinkled throughout the script, they’ll start to feel like filler, or worse, a crutch.

Not necessarily. Some writers lean into true dream logic: nonlinear events, emotional distortions, reality shifts. Others go for clarity, symbolism, or heightened realism.

The rule of thumb is that your dream logic must match your story’s logic. If your film is grounded, keep dreams emotionally truthful and stylistically modest. However, if your film is stylized, feel free to stretch the world further in dreams.

You’re not recreating actual sleep but dramatizing the subconscious.

Conclusion

Dream sequences are powerful because they bypass logic and go straight for meaning. When done well, they reveal the soul of a character. When done poorly, they feel like cinematic filler: indulgent, confusing, or cliché.

To write dream sequences that stick:

- Give them purpose.

- Make them character‑driven.

- Format them clearly.

- Borrow style consciously (surreal or hyper-real or something in between).

- Avoid classic pitfalls like dream‑ending twists or exposition dumps.

Above all, remember this: A good dream sequence doesn’t distract from the story. It exposes the story the character would never willingly tell.

Ready to write your masterpiece?

Start your next script for free in Celtx.

Up Next:

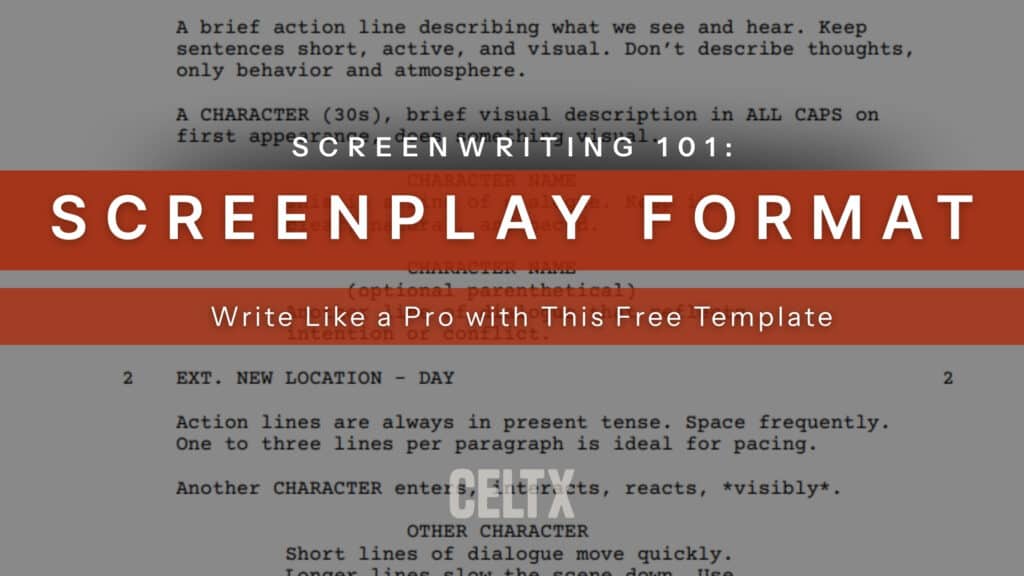

Screenplay Format 101: Write Like a Pro with This Free Template

Dreams, flashbacks, montages—every storytelling device still has to live inside clean, professional script pages. Here’s a step-by-step guide to industry-standard screenplay format, with examples you can follow as you write in Celtx.