“When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

That line from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance is the essence of the Western. But the genre isn’t all about gunslingers and sunsets but about mythmaking: the morality tales written in dust, sweat, and blood.

Whether your frontier stretches across the plains of Montana, the deserts of New Mexico, or the neon wastelands of a futuristic city, writing a Western means wrangling with timeless questions: What makes a hero? What does justice cost? And what does civilization really mean when there’s no law to lean on?

In today’s blog, we’ll explore the core themes of western movies and TV shows, popular characters and how you can set killer scenes.

Let’s saddle up.

Table of Contents

- The Open Range

- Core Themes of the Western Genre

- The Cast of the Frontier

- Setting the Scene

- The Modern Western (Neo-Western)

- Writing the Shootout

- Examples of Westerns in Film & TV

- FAQs

- Conclusion

The Open Range

The Open Range is the quintessential Western, but it’s more about ideology then geography. It’s the dream of endless land, of men and women defining themselves by grit and will alone. It’s the promise that, beyond the horizon, there’s freedom, even if it’s fleeting.

The Western myth is born from contradiction, about the birth of civilization and the death of freedom. Every fence post is a symbol of progress and a eulogy for the wild.

When you write a Western, you’re writing about the tension between order and chaos, freedom and belonging, myth and man.

The Western is America’s creation myth, retold through the eyes of loners, lawmen, and outlaws. But it’s also adaptable. That’s why we see its echoes in outer space (The Mandalorian), dystopian futures (Westworld), and neo-noir crime sagas (No Country for Old Men).

Core Themes of the Western Genre

At its heart, the Western is moral storytelling stripped to the bone. Its themes of civilization vs. wilderness, justice vs. vengeance, and law vs. chaos have shaped storytelling since the first campfire tales.

Here are three of the main themes that have defined the Western:

1. Civilization vs. Wilderness

The frontier is always a battleground between what we build and what we destroy. The dusty main street and the endless plains are moral landscapes for the action that takes place.

The town represents order, community, and the hope for peace. The wilderness means freedom, temptation, and danger.

And your hero? He usually straddles the line between both. He or she has one foot in the wild and one foot in the world that is trying to tame it. Shane wants peace but knows he can’t live among the civilized. Wyatt Earp enforces the law but secretly craves the chaos that gave him purpose.

2. Morality

In the Western, morality is simple, but not easy. Right and wrong are clear, but doing the right thing usually comes with a cost. Your hero often must choose between personal justice and moral justice, between saving their soul or saving the town.

Think Unforgiven; William Murray wants redemption, but he can’t escape who he was. The film’s final act reminds us that sometimes the only way to restore order is through violence, and that leaves no one pure.

3. Justice

The law in the West is written in blood, not books. When the sheriff’s office is empty and the nearest court is three days’ ride away, justice becomes personal. It’s why Westerns resonate so much. They force characters and audiences to confront what justice looks like when the rules don’t apply.

The Cast of the Frontier

Every Western thrives on its archetypes. These aren’t cliches but mythic roles that speak to something primal in the human condition.

The Hero

The Western hero is a paradox. They’re the one who can restore order, but only because he lives outside. They’re stoic, burdened, and often doomed to ride off into the sunset once the job’s done.

Clint Eastwood’s “Man with No Name” is the ultimate archetype. He’s mysterious, morally ambiguous, and competent to the core. He not only seeks but enforces redemption. His internal conflict is central to the story.

When writing her hero, remember their silence speaks louder than dialogue. Let their actions define them.

The Villain

A good Western villain is more than a mustache-twirling outlaw. They’re a reflection of a hero; the same code twisted by greed or cruelty.

Think Liberty Valance, Frank (in Once Upon a Time in the West) and Anton Chigurh (No Country for Old Men). All of these characters embody chaos and test the hero’s values, not just their trigger finger.

And it’s not just Westerns that have key character archetypes. Check out our list of horror archetypes here.

The Damsel (and Beyond)

Traditionally, Westerns wrote women as damsels, saloon girls, or settlers. But modern Westerns have evolved. Today’s frontier women are just as layered and dangerous as the men, from Jane Campion’s The Power of the Dog to Godless’s all-female town.

Whether your female lead is a gunslinger, a widow, or a survivor, she should embody the same moral weight as her male counterparts. The West belongs to everyone now.

Setting the Scene

The Western’s world is its soul. You can’t fake the frontier; it’s as much as character as your hero. So, what key pieces of scenery do you need?

The Town

The town represents the edge of civilization, a fragile bubble of order surrounded by wildness. From the saloon to the church and the jailhouse, each one is symbolic.

Use the town to show progress and decay side by side. A church being built while the saloon thrives? That’s visual storytelling gold!

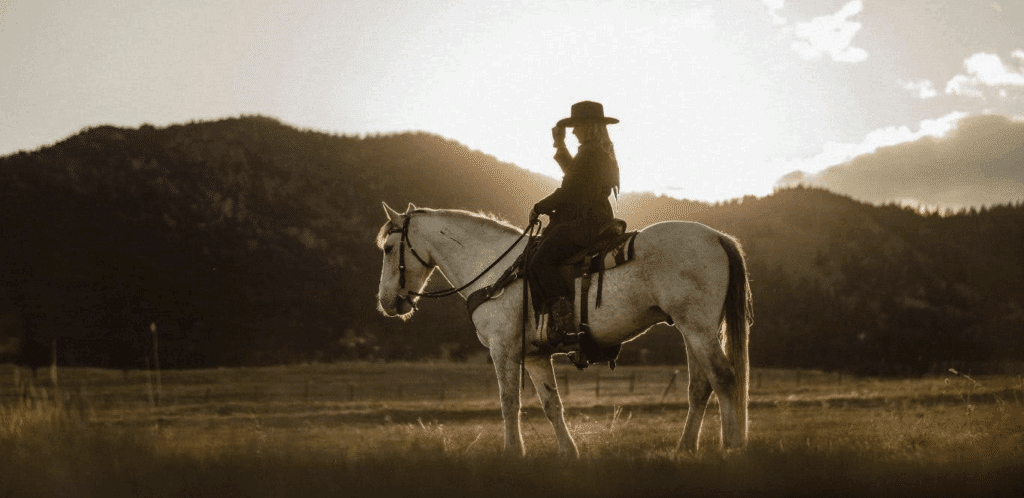

The Wilderness

The wilderness is freedom incarnate that’s vast, indifferent, and most of all deadly. When your characters venture into it, they’re facing not just nature but their own souls.

Describe your wilderness with reverence and menace. “The land was hard, but it was honest”: that kind of prose evokes the mythic quality of the Western landscape.

The Saloon

Every Western needs a saloon. It’s where alliances form, gunfights start, and morality gets blurred by whiskey and piano tunes. It’s your microcosm of the West: a mix of lawmen, drifters, gamblers, and dreamers, all under one smoky roof.

The Modern Western (Neo-Western)

The Western never died. It just put on new boots. The Neo-Western takes the moral codes and landscapes of the classic Western and transplants them into new genres and settings.

The Crime Western

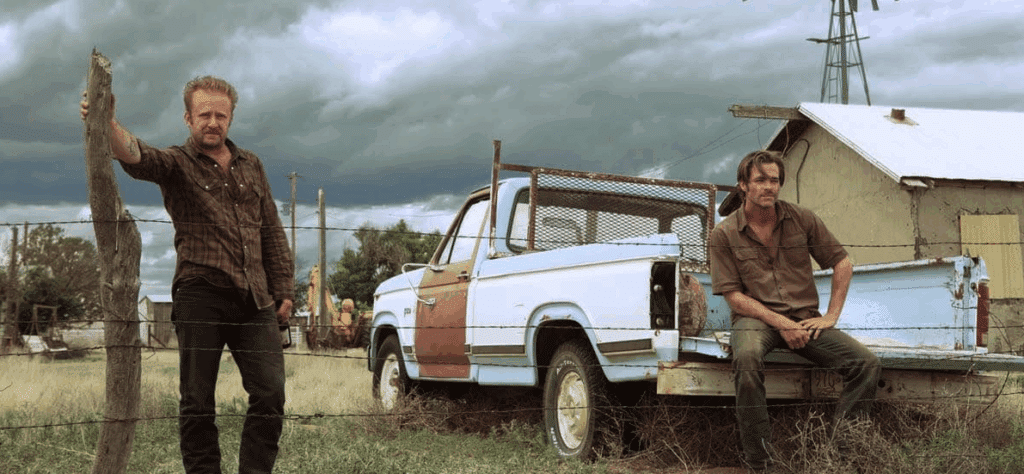

Western movies like No Country for Old Men, Hell or High Water, and Sicario bring themes into modern America. The open range becomes empty highways and desolate suburbs. The outlaw wears a suit instead of a poncho, but the moral tension remains the same.

The Sci-Fi Western

Firefly, The Mandalorian and Westworld all channel the Western’s frontier energy into space and future worlds. They explore the same ideas: who holds power on the edge of civilization, and what happens when freedom runs out.

The Prestige Western

Yellowstone, 1883 and The Power of the Dog prove the Western still thrives in prestige storytelling. They embrace complex psychology, flawed heroes, and the legacy of violence that built the frontier.

Writing the Shootout

You can’t talk Westerns without gunfire. But a great shootout isn’t about bullets but about tension.

1. Build the Moment

A Western shootout is a duel of souls. It’s about who’s right, who’s ready, and who hesitates.

Don’t rush to the trigger pull. Draw out the silence, the close-ups, the wind in the dust. Let the audience feel the inevitability.

2. Keep It Clear

In screenwriting, clarity beats chaos. Use concise action lines:

The street empties. Boots scrape on dust. Fingers twitch near the holster.

Short sentences and tight pacing are the rhythm of a gunfight.

3. Make It Moral

A good Western shootout is a judgment. The hero doesn’t shoot because he can. He shoots because he must. Every bullet carries a choice.

While this is a great guide, how Westerns are physically filmed has also evolved. Usually filmed in primarily wide-shot, close-ups have become more popular. See why in this article from No Film School.

Examples of Westerns in Film & TV

The Western’s legacy stretches far beyond the tumbleweeds of the 19th century. Each era redefines the frontier, from John Wayne’s moral deserts to Taylor Sheridan’s ruthless ranches. This proves that the West never really closed.

Let’s take a look at some of the most iconic examples of Western movies:

Classic Westerns

Classic Westerns like High Noon (1952), Shane (1953), and The Searchers (1956) defined the mythic foundation: lone heroes facing moral reckonings under endless skies. They taught screenwriters that the West isn’t just a setting, but a crucible for conscience.

Spaghetti Westerns

Italian filmmakers like Sergio Leone reinvented the genre with grit, irony, and operatic style. A Fistful of Dollars (1964), The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966), and Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) turned silence, music, and close-ups into storytelling weapons. Their lesson: minimal dialogue, maximum tension.

Revisionist Westerns

The Revisionist Westerns like McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971), Little Big Man (1970), and Unforgiven (1992) stripped the genre’s romanticism away, exposing the moral ambiguity beneath. These films transformed the cowboy from savior into survivor, from legend into man.

Neo-Westerns

In the 21st century, the Neo-Western revived the genre’s spirit in modern settings. No Country for Old Men (2007), Hell or High Water (2016), and Wind River (2017) trade horses for highways but keep the same code: justice, isolation, and the slow death of old values. Lesson: the frontier now lies in empty towns, borderlands, and moral gray zones.

Television

Television embraced the long game. Deadwood (2004–2006) made the West Shakespearean; Justified (2010–2015) gave it a Southern drawl; Yellowstone (2018–present), 1883, and Westworld reinvented the myth for modern audiences. These shows prove the Western is an ongoing argument about power, progress, and belonging.

Every Western, from Stagecoach to Yellowstone, asks the same question: when the law runs out, what kind of person do you become? That’s why the genre endures; because every frontier, old or new, tests the soul.

John Ford’s Westerns were renowned in the industry. Find out how much so in this article.

FAQs

A classic Western is set in the frontier era (roughly 1860–1910) and deals with themes of settlement and survival.

A Neo-Western keeps the same moral DNA but moves it into the modern world. Think Hell or High Water instead of The Magnificent Seven.

– The lone gunslinger

– The frontier town

– The showdown at high noon

– The saloon brawl

– The moral reckoning (law vs. justice)

– The ride into the sunset

These tropes endure because they’re mythic shorthand for courage, redemption, and loss.

A Spaghetti Western refers to Westerns made by Italian filmmakers (often shot in Spain) in the 1960s. They were grittier, bloodier, and morally ambiguous. Think Sergio Leone’s Dollars Trilogy.

There’s no single answer, but the short list usually includes The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, Unforgiven, High Noon, and The Searchers. Each defined the genre in its own era.

Conclusion

The Western endures because it asks timeless questions: What makes a person good? What makes them dangerous? What’s worth fighting for when the law can’t save you?

It’s a genre that thrives on contradiction: the beauty of violence, the cost of progress, the loneliness of freedom. So, when you write your Western, remember you’re not just writing about guns and grit. You’re writing about the myth of America, about morality stripped bare in the blinding sunlight.

Up Next:

Mastering Film Genres: The Definitive Screenwriter’s Guide

Explore the bigger picture of genre writing—from structure to tone to audience expectations—and see how every genre connects back to the fundamentals of great storytelling.