Introduction | How to Format a Script

Imagine picking up a screenplay that’s cluttered, inconsistent, or just plain difficult to follow.

It could be the most compelling story ever written, but improper formatting can create a real headache for a reader. For screenwriters, mastering screenplay formatting is essential, not only to maintain professionalism but also for the clarity and readability of their work.

In today’s article, we’ll guide you through the fundamentals of script formatting, the pitfalls you need to be avoiding, and all the tools you’ll need to streamline your formatting process.

You should then have a solid grasp of how to present your screenplay to meet the ever-demanding industry standards of the film and television world.

FAQ: What is a screenplay?

Put simply, a screenplay is a 90-120 page document, typed in Courier 12pt font on 8.5″ x 11″ white paper with three holes. One page in Courier font roughly equals one minute of screen time. This helps writers gauge the duration and pacing of their story for a better writing and viewing experience.

In this Article

- Why Formatting Matters in Screenwriting

- The Basics of Screenplay Format

- Common Script Formatting Mistakes and How to Fix Them

- Resources to Continue Learning

- How Celtx Simplifies Script Formatting

- Conclusion

Why Formatting Matters in Screenwriting

Formatting is so often talked about in screenwriting circles, but just why is it so important?

Firstly, a screenplay isn’t just about storytelling; it’s a blueprint for production. Directors, actors, cinematographers, and editors all rely on the script’s format to interpret scenes efficiently. Film and television production demands clear timescales, budgets, and logistics so to have everyone on the same page with a formatted script is invaluable.

A script must be understood by an entire production crew. Industry-standard formatting ensures that all scripts are easy to read and understand. Over the years, this has become an expectation from executives and producers to receive properly formatted scripts. Anything less can lead to immediate rejection.

By adhering to the conventions of script formatting, you as a screenwriter demonstrate that you’re serious about your craft and are ready to work within the industry.

Related Reading: How to Get a Screenwriting Agent (The Right Way) || Celtx Blog

Basics of Screenplay Format

We’ve already talked a lot about formatting expectations so let’s explore what they actually are. Screenplays follow a standardized format that is essential for industry professionals. Here are the core components:

Scene Headings (Sluglines)

Scene headings (also known as sluglines) indicate the location and time of a scene. They are always written in uppercase and follow this format.

INT/EXT. LOCATION – TIME OF DAY

Start by indicating whether the scene is interior (INT) or exterior (EXT), before moving onto the location and time of day.

INT. COFFEE SHOP – DAY

EXT. PARKING LOT – NIGHT

If a scene transitions between locations, you can use INT/EXT. and vice versa.

Action

Action lines describe what is happening in the scene. They should be concise, written in the present tense, and avoid excessive descriptive detail.

Good action descriptions focus on what can be seen and heard.

John enters the dimly lit room, scanning for any signs of movement. A chair creaks in the corner. He reaches for his gun.

Avoid over flowery prose or internal thoughts that cannot be visualized on screen. For more tips, check out our blog on how to write action lines that make your script move.

Dialogue

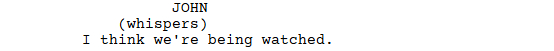

Dialogue follows the character’s name, which is centered and written in uppercase. The dialogue itself is placed beneath it, indented from both margins.

Let’s see how this is mapped out on a script:

Notice how we’ve used a parenthetical just before the dialogue. Use these sparingly to indicate tone or small actions. However, make sure to only use them when necessary.

Related Celtx Content: What are Parentheticals? When, How, and Where to Use Them? || Celtx Blog

Transitions

While many modern screenplays avoid explicit transitions, they can still be used when necessary.

CUT TO: indicates a direct cut to another scene.

FADE IN:/FADE OUT: is used at the beginning or end of a screenplay.

DISSOLVE TO: indicates a passage of time or a change in tone.

Transitions are always aligned to the right margin of the page, like this:

Formatting Rules

Alongside the screenplay elements detailed above, there are rules on how these should be presented on the page.

- Always use 12-point Courier Font.

- 1-inch margins on all sides, with a 1.5-inch margin on the left for binding.

- Single-spaced lines for action and descriptions. Double-spaced between scene headings, action and dialogue.

- In terms of page length, a feature script is typically between 90 and 120 pages, with one page roughly equating to one minute of screen time.

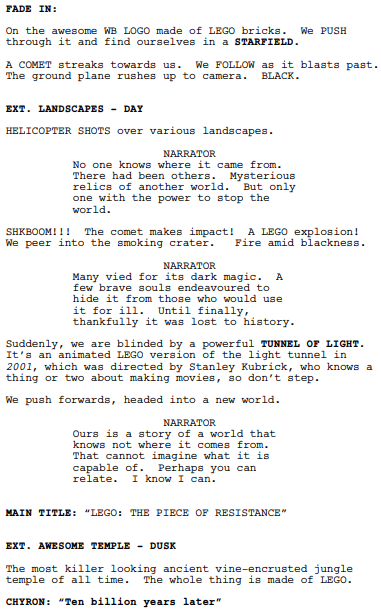

Now we’ve covered all the building blocks of a screenplay, let’s look at everything in action. Here’s the opening page of The Lego Movie (2014).

Screenplay formatting shouldn’t slow you down.

Celtx automatically formats your script as you write, so you can focus on the story — not the margins. With hotkeys and intuitive tools, you’ll stay in the flow and get your ideas on the page effortlessly.

Try Celtx today and write without limits.

Common Script Formatting Mistakes and How to Fix Them

Many beginner screenwriters (and some experienced ones!) make formatting errors that can harm their script’s readability and professional appeal. Here are some common mistakes and how to fix them:

Overwriting Action Descriptions

Keep action lines concise and visual and avoid long paragraphs with unnecessary detail.

Which one of these action line examples do you feel is most effective?

This:

John walks slowly into the room, hesitating before cautiously reaching for the doorknob, his breath quickening as he anticipates what might be on the other side.

Or this:

John hesitates, then grips the doorknob. He exhales sharply before stepping inside.

Both examples depict the same scene, however example one would be best suited for a novel. The second example is more visual and is more at home in a screenplay.

Incorrect Dialogue Formatting

Ensure character names are in uppercase, and dialogue is properly indented. Avoid excessive parentheticals or unnecessary dialogue tags.

For instance, instead of writing:

Simply write:

Ultimately, don’t overcomplicate things or feel you need to describe actions and dialogue in huge detail. Focus on visuals!

Excessive Use of Camera Directions

Let the director and cinematographer handle shot selection unless it’s necessary for storytelling. Instead, hone in on the visual impact of a moment through action.

So, instead of writing:

Camera zooms in on Sarah’s face.

Why not try:

Sarah’s eyes widen. Her breath catches.

The second action line doesn’t mention a camera at all, yet we know that Sarah’s eyes in this moment are important as the writer has highlighted it.

Mixing Tenses

Always write in the present tense. A common mistake is a shift between past and present. Avoid writing action lines such as:

John walked into the room and looks around.

Instead, maintain present tense:

John walks into the room and looks around.

Improper Scene Headings

Ensure your sluglines are formatted correctly, clearly stating the location and time of day. Keep your headings specific and consistent all the way through your script, avoiding examples like this:

SOMEWHERE IN THE FOREST – NIGHT

Instead:

EXT. DENSE FOREST – NIGHT

Too Many Parentheticals

Yes, parentheticals can be helpful in determining the tone or specifics of a line of dialogue. However, excessive parentheticals clutter the page and ultimately slow down the read.

Use them when needed, like when you’re indicating sarcasm, whispering or direct actions that impact a line’s delivery.

Overuse of Capitalization

Reserve capitalization for character introductions, major sound effects, and significant visual cues. Writing:

JOHN SLAMS THE DOOR SHUT AND STARTS SCREAMING could be jarring.

Instead, highlight only essential elements:

John slams the door shut. He SCREAMS.

Here, the scream is what stands out, drawing our eyes to it, and making his scream the focal point of the line.

Ignoring Page Length Guidelines

While creativity is of course, extremely important, script should generally adhere to industry-standard length.

A 150-page screenplay for a drama will likely need to be trimmed or be passed over by an executive, whereas a 60-page feature script may be deemed too short.

Bear in mind the page length guidelines based on the project you’re writing.

Resources to Continue Learning

As with all art, screenwriting is an ongoing learning process. Whether you’re a fledgling writer or very experienced, there are always elements of your craft you’re wanting to develop.

Here are our top picks of the resources you need to help refine your skills.

Books

While there are countless screenwriting books out there, promising to revolutionize your creative process, it’s crucial that you take on board advice that works for you. You won’t agree with everything you read, and that’s okay! After all, art is subjective, and that applies also to screenwriting.

In no particular order, here are the books we recommend to set you off on your way:

- The Foundations of Screenwriting by Syd Field is a fantastic foundational book that explains the three-act structure and core screenplay mechanics.

- A must-read for understanding storytelling structure and pacing, be sure to pick up Save the Cat! by Blake Snyder.

- David Trottier’s The Screenwriter’s Bible is a comprehensive guide covering format, structure and reams of industry tips.

- My personal favorite Story by Robert McKee explores the principles of storytelling and character development in depth.

Or if you’re looking for a super practical guide to writing compelling and marketable scripts, Writing Screenplays That Sell by Michael Hague is the book for you.

Online Courses

If cozying up with your laptop, a notebook and a cup of coffee is more your vibe, there are so many online courses on offer at every budget. Let’s take a look at a few:

- Masterclass (featuring Aaron Sorkin, Shonda Rhimes, and many others) sits you down with an industry expert in storytelling, dialogue, and script development.

- ScreenwritingU offers professional-level courses and mentorships for screenwriters at various levels.

- Udemy’s screenwriting courses are super affordable, covering everything from screenplay structure, formatting and industry insights.

- The Writers’ Guild Foundation provides educational resources, workshops, and seminars for aspiring screenwriters.

- Coursera (University of East Anglia’s Screenwriting Course) is a free resource that covers the fundamentals of screenwriting.

Software and Websites

The internet is a myriad of information that can be very overwhelming for writers. So instead of you trawling through thousands of Google results pages trying to find what you need, here are some websites and software options to help you on your way.

- First, we have The Black List, a platform for screenwriters to receive feedback and connect with industry professionals.

- IMDbPro is ideal for studying professional screenplays and networking with industry contacts.

- Offering screenwriting contests, workshops and mentorship opportunities, ScreenCraft is another great place to network.

- The Script Lab provides script breakdowns, industry advice, and educational articles.

- Final Draft is the industry-standard software for screenwriting, often used by professionals.

- For those more experienced writers looking to take the next step into formal education, the courses LA Film School are second to none!

- Of course, this would be a Celtx list if we didn’t shout out our fabulous screenwriting software! Here to guide you through your entire production process, you won’t need any other software.

- Also, for more educational articles like this one, check out our Celtx Blog which dives deep into the need-to-knows of the film and television industry!

All these resources can not only help you sharpen your writing skills, but to understand industry expectation and ultimately increase your chances of success in the competitive world of filmmaking.

How Celtx Simplifies Formatting

If you didn’t know already, Celtx is a powerful tool that makes screenplay formatting easy and accessible for writers of all levels. We’re here to simplify the writing process, not overcomplicate it! Here’s how:

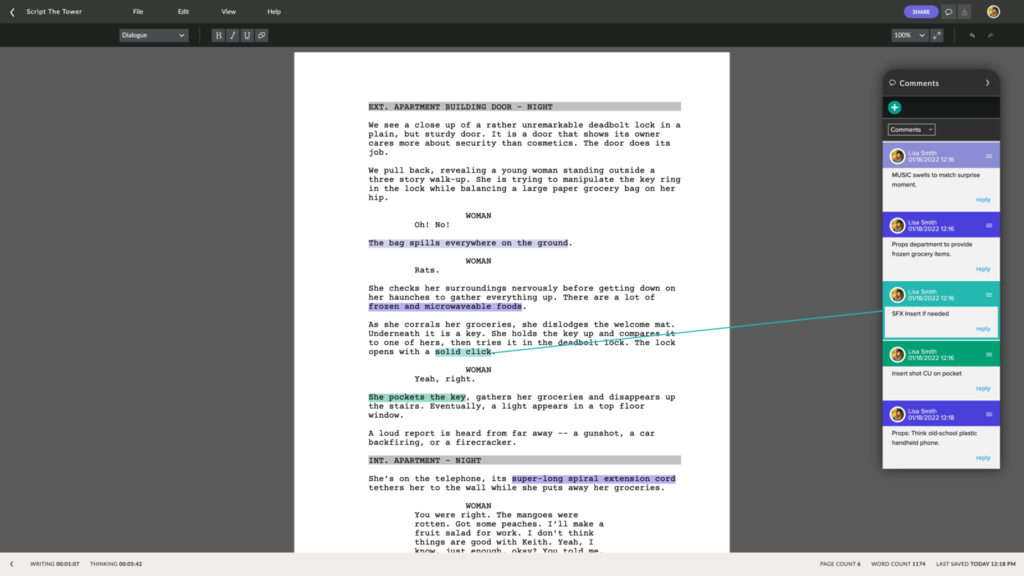

Automatic Formatting

Celtx automatically applies industry-standard screenplay formatting, ensuring proper margins, font, and spacing without requiring manual adjustments.

Script Templates

Our film, television, and theater templates make it super simple to start a new project with the correct structure inputted for you. We even have planning tools such as beat sheets, call sheets, and storyboards integrated into the software for easy switching between outline and script.

Free Call Sheet Templates || Free storyboard templates

Intuitive Interface

Our user-friendly interface allows you to focus on storytelling rather than technical formatting details.

Collaboration Features

Celtx enables real-time collaboration, making it easier for writers, directors, and producers to work together on script, no matter where they are in the world.

It doesn’t stop there! In addition to screenwriting, Celtx offers tools for scheduling, budgeting, and script breakdowns, making it a comprehensive solution for film and television production.

Get started with Celtx for free!

Conclusion

Mastering script formatting is an essential skill for any screenwriter aiming to create a professional, industry-standard screenplay. Proper formatting ensures clarity, readability, and efficiency throughout the production process, making it easier for directors, actors, and crew members to bring your vision to life.

By understanding the fundamentals you’ll not only improve the readability of your script but also increase your chances of success in the competitive world of film and television.

Avoiding common formatting mistakes, utilizing valuable resources and screenwriting software like Celtx can streamline your writing process and keep you focused on storytelling rather than technical details.

Now that you have the tools and knowledge, it’s time to put them into practice. Open your script, start writing, and craft a story that’s as compelling on the page as it is on the screen!

Ready to get started? Try Celtx today for seamless scriptwriting:

Continue learning with these Celtx articles:

- Mastering the Art of Screenwriting: The Celtx Screenwriting Series

- How to Format Dialogue in Screenplays: Rules You Need to Know

- How to Write a Good Story Using the Five-Act Structure