Flashbacks are one of storytelling’s oldest tricks, and one of its most abused. When done well, a flashback feels like a revelation or a puzzle piece snapping into place. It can reveal why your character fears the dark, flinches at a particular piece of music, or refuses to trust the charming stranger who seems perfectly harmless.

When done poorly, a flashback is the narrative equivalent of someone pausing a juicy story to explain everything that happened three years ago, who was dating whom, what the room smelled like and the complete genealogical history of the family cat. Nobody wants that.

In today’s blog, we’ll talk about how to write flashbacks the right way. We’ll cover when to use them, how to format them, how not to dump information like a bucket of wet cement, and why the past is only powerful when it actually matters to your present story.

Let’s get into it.

The Past Informs the Present

Humans are walking archives of memory. We’re all shaped by the things that happened to us, from traumas to triumphs, first crushes to humiliating middle-school talent shows, childhood pets to broken hearts, to near misses, and narrow escapes. Great characters deserve the same.

A flashback works when the past meaningfully changes how we understand the present. It’s narrative ammunition. The past is leveraged to deepen what’s happening right now.

A well-placed flashback will:

- Change our understanding of what’s happening.

- Shift our emotional alignment.

- Reveal a missing piece of the story.

- Reveal something about a character’s inner conflict.

- Raise the stakes by showing us what the character lost or fears losing again.

Used correctly, a flashback can help create momentum in a story.

When to Use a Flashback (The Narrative Rule)

It’s all well and good knowing what a flashback is but when exactly do you use one. The golden rule is to use them only when the past information is necessary for the current conflict.

If your current scene is perfectly understandable without the flashback, you probably don’t need one. If your character’s actions or emotions seem confusing, yet you know they’re rooted in something that happened before, then a flashback might be the perfect tool.

Ask yourself:

- Does the audience need this information now?

- Does the story become stronger because of this reveal?

- Is this the right moment emotionally for the character to relive this past event?

Think of it as using headlights while driving at night. You turn them on when you need clarity, not just because they look pretty.A flashback also needs to payoff at the end of your screenplay, otherwise it’s just taking up valuable time and space.

The Crucial Formatting (The Technical Rule)

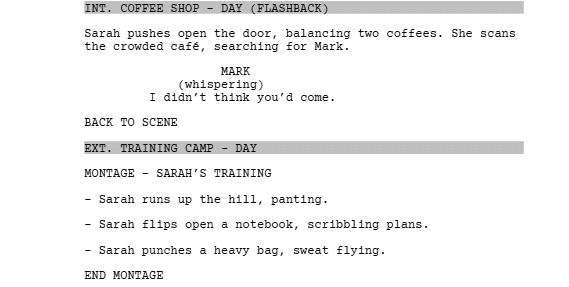

This is where many writers panic, but don’t worry. Formatting flashbacks isn’t complicated once you understand the two essential ingredients.

1. How to Start a Flashback

Indicate a flashback using the scene heading:

INT. KITCHEN – NIGHT (FLASHBACK)

Screenwriters use different styles, but the key is both consistency and clarity. The word FLASHBACK must ideally appear in the scene heading so there’s no mistaking the shift in time.

2. How to End a Flashback

There are two common methods:

Method 1: Scene Heading

BACK TO PRESENT

Then continue with a normal scene heading like:

INT. KITCHEN – NIGHT

Let’s see these on the script page:

Method 2: Action Line

Your return to the present is written as a standalone line before transitioning back to the ongoing action. Like this:

Both these methods work but pick one and stick to it.

3. Flashbacks vs. Montages vs. Dream Sequences

You may have noticed a montage in our example script. Believe it or not, it’s easy to confuse flashbacks and montages.

These cousins can cause a lot of trouble because they do look similar at first glance. Let’s clear up the confusion:

Flashback

- A character recalls an actual event from their past

- It contains true narrative information

- It explains or motivates something happening in the present

Dream Sequence

- Not necessarily real

- A character’s interpretation, fear, desire, or subconscious stew

- It uses dream logic, symbolism, exaggeration, surreal imagery

Montage

- A sequence of quick scenes or images

- Used to show progression, training, growth, decline, a journey, or emotional transformation

- Not inherently linked to memory

Here’s the simple rule of thumb. If it happened before the story and matters now, it’s a flashback. If it’s happening in the character’s head, it’s a dream. And if you’re showing a series of short beats to move time quickly, it’s a montage.

Mislabeling these can confuse the reader, and if there’s one thing you never want, it’s a confused audience.

Avoiding “Info-Dumping”

A flashback is meant to be powerful, revealing, and emotional. It’s not a dumping ground for exposition you didn’t know how to fit into the story.

Info-dumping is when a writer uses a flashback to shove information at the audience instead of weaving it into the narrative naturally.

So how do we avoid this trap as screenwriters?

Keep It Short

A flashback rarely needs more than a page or two. If it goes on for five pages, you might be accidentally writing a prequel.

Keep It Focused

The flashback should target one specific emotional or narrative reveal, not twelve.

Keep it Visually Driven

Film is a visual medium; flashbacks are the perfect opportunity to show instead of tell.

Wrong:

She remembered that her father used to tell her to be brave.

Right:

Her father kneels beside her, pressing a flashlight into her tiny hand. “You don’t run from the dark,” he whispers. “You face it.”

Suddenly, when adult-her refuses to enter the basement, the contrast hits emotionally. The flashback must sharpen the present moment, not overshadow it.

And for more tips on how to write killer flashbacks, check out this awesome video from a prolific screenwriter who has contributed to this very blog, Neil Chase:

Flashback Example Analysis

Let’s examine how some of the world’s beloved stories use flashbacks with surgical precision.

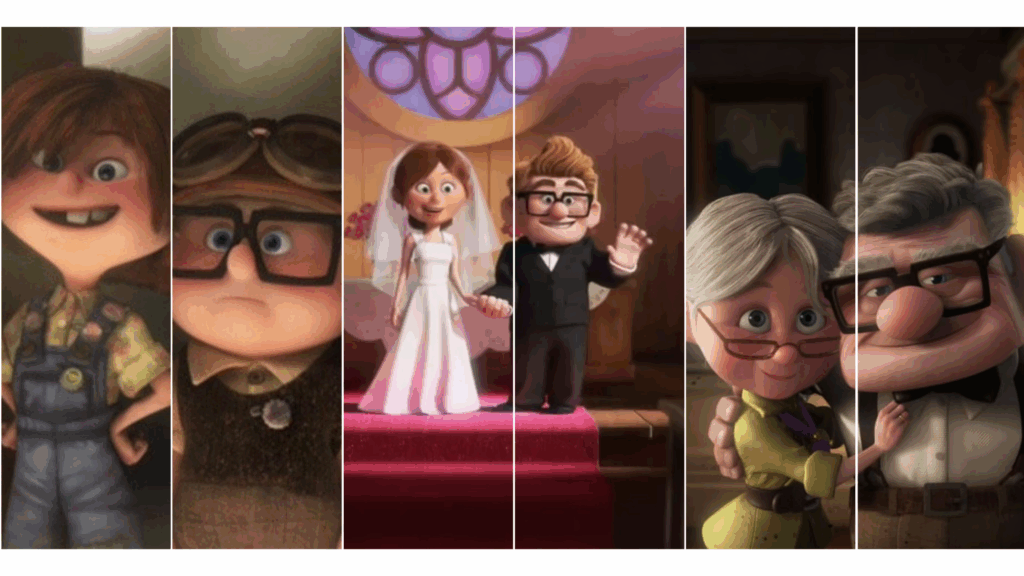

Up (2009) | The “Married Life” Sequence

This sequence isn’t technically a flashback in the purest structural sense, it’s more of a chronological montage, but it functions as a flashback device because it recontextualizes Carl’s motivations for the entire film.

The filmmakers show Carl and Ellie’s life together:

- Their dreams of Paradise Falls

- Their love

- Their hardships

- Ellie’s death

This emotional backstory isn’t placed randomly. It’s positioned at the start so that we instantly understand Carl’s stubbornness. His attachment to the house makes emotional sense and every scene afterward is infused with memory and loss.

Pixar doesn’t rely on dialogue but on visual storytelling.

Lost (2004-2010) | Use of Flashbacks as Structure

Every episode of Lost uses flashbacks as a narrative skeleton. But the key is that each flashback directly informs the present conflict.

For example:

- An episode where Jack struggles to lead the survivors is paired with a flashback where he confronts his father.

- A moment where Sun makes a dangerous decision is paired with a flashback revealing her marriage’s hidden fractures.

- Sawyer’s con-man tendencies are constantly framed through flashbacks that reveal the trauma fueling them.

Lost uses flashbacks as the emotional DNA of every episode. They explain not only what characters are doing, but why they are the way they are. If your flashbacks can accomplish that, you’re doing it right.

The Godfather Part II (1974) | Dual Timelines

Coppola’s masterpiece intercuts between present-day Michael Corleone consolidating power and past Vito Corleone rising in the criminal underworld. These Vito flashbacks are parallel and contrast with Michael’s arc.

We see:

- Vito’s rise fueled by necessity

- Michael’s descent fueled by paranoia

- One building a family

- One losing it

This is flashback as commentary, tragedy and character judgment. If your flashbacks can echo or contradict the present storyline, you’re writing on a Godfather-level wavelength.

Slumdog Millionaire (2008) | Flashbacks That Answer Questions

The entire movie is structured around the question: How does an uneducated boy know the answers to every question on “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?”

Each answer leads into a flashback that explains:

- The knowledge he gained

- The trauma he survived

- The love he lost

- The people who shaped him

Here, flashbacks are the engine of the story. Each one unlocks understanding and maintains suspense.

Finding Nemo (2003) | The Devastating Opening Flashback

Before the title card even appears, we witness:

- Marlin losing his wife

- The barracuda attack

- The single egg he saves (Nemo)

This flashback explains everything about Marlin’s overprotectiveness, Nemo’s frustration, and the emotional stakes of the journey. You feel for Marlin instantly because you know what he’s trying to protect.

Batman Begins (2005) | Trauma That Fuels a Hero

Christopher Nolan uses flashbacks like therapy sessions—each one peeling away a layer of Bruce Wayne’s psychology.

The flashbacks show:

- His fear of bats

- His parents’ murder

- His guilt and anger

- His desire for justice (and revenge)

These aren’t random glimpses of childhood. They explain the symbol, the mission, and justify the obsession.

In superhero movies, flashbacks often feel obligatory, but not here. They’re the skeleton key to the entire character.

Write complex narrative structures with ease. Start writing with Celtx today, it’s free.

The Haunting of Hill House (2018) | Flashbacks That Alter the Meaning of Events

Mike Flanagan’s series is a masterclass in weaving timelines.

Flashbacks reveal:

- What actually happened in the house

- Why each sibling is traumatized

- How childhood fears ripple into adulthood

Most importantly, the flashbacks recontextualize scenes we thought we understood. A moment that looked supernatural becomes psychological and vice versa.

The present only becomes clear when the past becomes known. A perfect flashback strategy.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) | Memories in Reverse

This film uses flashbacks as the literal architecture of its plot. Joel undergoing a memory-erasure procedure is just the frame; the real story is in the flashbacks:

- His relationship with Clementine

- Their joy, arguments, quirks, and heartbreak

- The moments he wishes he could forget, and then wishes he could keep

Flashbacks here reveal character, deepen emotional stakes, and build a reverse-chronology romance. When flashbacks control the structure like this, the audience becomes active participants, piecing together a relationship as it disappears.

Flashbacks are present in so many movies, including Memento as explored here.

FAQs

No, a flashback is a memory of something that actually happened. A dream sequence is symbolic, imaginative, or subconscious.

If your character wakes up afterward, you wrote a dream, not a flashback.

Use BACK TO PRESENT, either in a scene heading or on an action line. Both are correct. Clarity is what matters.

Yes, but each one must follow the narrative rule: Only when the past is necessary for the present.

If you find yourself writing dozens of flashbacks to “fill in history,” your story might be starting in the wrong place. Flashbacks are seasoning, not the main dish.

A flashback moves backward in time. A flash-forward jumps ahead to reveal future events. Both must serve the present narrative, be clearly formatted, and be used deliberately.

A flash-forward can raise suspense (“How do we get to that future?”), while a flashback deepens understanding (“Oh, that’s why this character is like this.”). Use each purposefully.

Conclusion

Flashbacks are one of the most potent tools in your storytelling arsenal, but only if you use them with intention. They’re not decorations, shortcuts, or nostalgia buttons you press to get easy emotion.

A flashback is a deliberate incision into the past that reveals something essential about your present story. When you follow the rules, using flashbacks only when necessary, formatting them clearly, keeping them focused, and avoiding info-dumps. You transform them from a clumsy interruption into a powerful narrative device.

The past matters. Your character’s memories matter. And when you wield them with purpose, your story becomes richer, deeper, and more emotionally resonant.

Ready to incorporate the past into your present story?

Let Celtx’s Script Editor automatically apply all industry rules while you focus on the story.

Up Next:

How to Write a Montage in a Script (with Formatting Tips)

Montages and flashbacks often work hand-in-hand to compress time and reveal character quickly. This guide breaks down how to format a montage properly—so you can keep your script clear, clean, and industry-ready.