Sometimes, the classics are the best, and this doesn’t just apply to our favorite novels, film series, or TV shows. Believe it or not, some of the best writing theories have been around for years, even centuries.

This includes the Iceberg Theory, a storytelling technique developed by renowned writer Earnest Hemingway.

Hemingway’s unique style of writing has been thoroughly studied for its use of simple yet impactful language, simultaneously packing a punch and effortlessly flowing. Hemingway always leaves us wondering, with much unsaid. In short – he’s an expert in subtext and coined the Iceberg Theory or ‘the theory of omission’.

Never heard of it? Well, that’s where we come in. In today’s blog, we’ll explore the Hemingway iceberg theory, show you it in action in literature and film, and most importantly, how you can employ it in your own writing.

Table of Contents:

- What is the Iceberg Theory?

- How Does the Iceberg Theory Work?

- The Hemingway Connection: Where It Originated

- Iceberg Theory Examples in Literature and Film

- Using Iceberg Theory in Your Writing: 9 Steps to Success

- Why Writers Should Embrace Subtext

- Conclusion

What is the Iceberg Theory?

Let’s get into it – what is the iceberg theory?

Take an actual iceberg: what we see above the water is only a small part of it (around one-eighth), with most of the iceberg existing under water and out of sight (around seven-eighths).

When it comes to creative writing, the iceberg theory implies that we should only reveal a small portion of what we know, leaving the rest ‘under the water’ or out of sight. Only we, as the writer, should know everything else. We then use this exclusive knowledge to inform our story’s events, characters and structure.

As the bottom of the iceberg is the strongest part in nature, then, in theory, should the unseen elements of our stories.

Readers are always great at reading between the lines, so we must cater to this. Not only does the iceberg theory allow readers to figure underlying themes, emotions and meanings out for themselves, but it also strengthens our narrative overall.

In short, the iceberg theory teaches us that there’s more to a story than what’s written on the page.

Start your next script with Celtx’s industry-standard screenwriting software—built for storytellers, screenwriters, and filmmakers at every level.

Start your 7-day free trial now!

How Does the Iceberg Theory Work?

Now we’ve explored the overarching concept of the theory, let’s break things down.

1. The Power of Omission

The iceberg theory relies upon omissions, but not just any old omissions. As writers, we shouldn’t just randomly exclude details. Instead, we should make strategic decisions on what not to include to infer details and allow readers to fill in gaps with their imaginations, feelings, and interpretations.

2. The Power of Subtext

Hiding between the definitive plot and dialogue, is subtext. Subtext is the unsaid feelings and motives behind what a character says and does. Sometimes we don’t always say or do what we mean, making subtext a powerful aspect of writing that allows us to depict events and stories as authentically as possible.

3. The Power of Trust and Respect

We must trust our audiences to ‘read between the lines’ when it comes to interpreting our stories. Instead of just receiving a story, the audience joins in the storytelling, adding their own splash of creativity.

4. The Power of Emotional Resonance

Again, this means allowing the audience to become involved in our stories, but emotionally. If a reader or viewer can give a part of themselves to the work, it resonates even more.

5. The Power of Suggestion

Rather than explaining explicitly, if we can simply suggest through subtle actions and thoughtful pauses, we can share important messages more effectively in our writing and create a treasure hunt for our audiences.

The Hemingway Connection: Where It Originated

I always try to write on the principle of the iceberg. There is seven-eighths of it underwater for every part that shows. – Ernest Hemingway

Hemingway began his writing career as a journalist, quickly adopting a minimalistic style due to the nature of reporting on immediate events that required little interpretation. In the 1920s, he covered the Greco-Turkish War. Here’s what his biographer, Jeffrey Myers in Hemingway: A Biography had to say about his reporting style:

“He objectively reported only the immediate events in order to achieve a concentration and intensity of focus—a spotlight rather than a stage” – Jeffrey Myers (1985)

As he transitioned into writing short stories, Hemingway continued to write minimally, maintaining the belief that a story’s deeper meaning shouldn’t be revealed on the surface, but should be deduced through covert methods.

Hemingway’s writing continued to develop as he worked on ways to shorten his prose, and how describing an action could evoke different meanings and responses. For him, the more a piece of writing was stripped back, the more powerful the story. It was this unique style that earned him the Pulitzer Prize in 1953 and the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954 for his novel The Man and the Old Sea, celebrated as a masterpiece of this understated style.

What’s beneath the surface of your story? Plan your next script with Celtx.

Iceberg Theory Examples in Literature & Film

Let’s take a look at some iceberg theory examples in action from both literature and film.

Examples in Literature

1. Hills Like White Elephants | Ernest Hemingway

It’d be rude to write a blog about a Hemingway theory and not include his work! In this classic story, the plot revolves around a conversation between a couple waiting for a train about an implied abortion. This isn’t explicitly mentioned, with the tension and emotions clear beneath their seemingly casual conversation. Hemingway, of course, leaves it to the audience to infer the situation from this dialogue, allowing them to actively participate in the story.

2. Brokeback Mountain | Annie Proulx

This short story which won the National Magazine Award for Fiction in 1998 that was soon adapted into film in 2005, tells of two cowboys who fall in love. While Proulx doesn’t explicitly discuss societal pressures or homophobia, we feel these themes beneath every word. It’s a great example of the iceberg theory and how what’s unsaid can be as powerful as what’s said.

3. The Great Gatsby | F. Scott Fitzgerald

One of Hemingway’s contemporaries, Fitzgerald is another master at hiding symbolism in the simplest of writing. In The Great Gatsby, Gatsby’s obsession with Daisy alongside his extravagant lifestyle symbolize deeper themes of the American Dream, disillusionment, and social class struggles.Hemingway, in one of his letters to Fitzgerald, said:

“I write one page of masterpiece to ninety-one pages of shit. I try to put the shit in the wastebasket.” – Ernest Hemingway

Even for the world’s most prolific writers, there’s always trimming and editing to do!

Examples in Film

Yes, it’s possible for screenwriters and filmmakers to adopt the iceberg theory! In essence, the theory is another iteration of ‘show, don’t tell’.

As with novelists, we must trust our audience to understand the story’s deeper meaning through subtle clues and what’s implied.

1. No Country for Old Men (2007)

Based on Cormac McCarthy’s novel of the same name, No Country for Old Men is filled with stretches of silence, minimal exposition, and unresolved questions.

Sheriff Ed Tom Bell represents the disillusionment of an aging lawman confronting the relentless modern world. Instead of explicitly showing the moral message, the film presents moments of quiet reflection, leaving the audience to ponder the nature of fate, justice, and the consequences of violence.

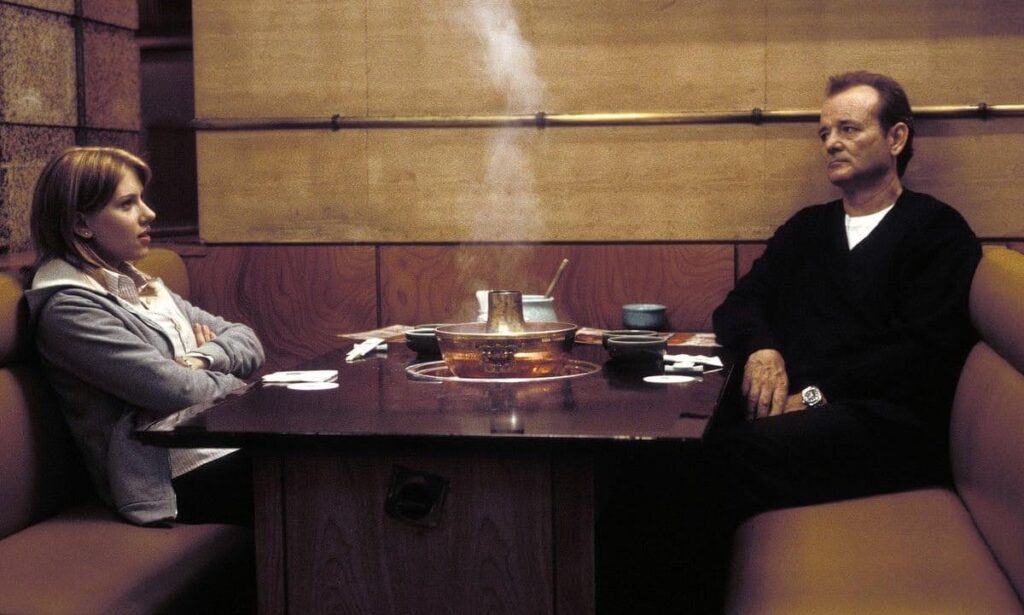

2. Lost in Translation (2003)

This is a great example of the iceberg theory being adopted throughout an entire movie. We meet Bob, an aging actor, and Charlotte, a young woman struggling with loneliness in Tokyo. Their conversations don’t reveal everything about them, or what they’re feeling. The pauses, unspoken thoughts and lingering glances help to visually depict this.

Even at the end of the film, we’re kept guessing as Bob whispers something to Charlotte before they part ways – something we don’t hear. Even long after the credits roll, we are left to interpret what was said and what it meant for the characters. It’s through this dialogue and subtext that the themes of loneliness, longing, and fleeting human connections are explored.

Using Iceberg Theory in Your Writing: 9 Steps to Success

Step 1 | Understand the Concept

The first step in using Hemingway’s Iceberg Theory in your writing is to understand the concept fully. This theory suggests that the deeper meaning of a story should not be evident on the surface. Instead, like an iceberg, the bulk of what you want to convey lies underneath the surface, hinted at but never explicitly stated.

Step 2 | Identify Your Iceberg

Once you understand the theory, identify your iceberg – the core idea or theme of your short story or novel. It could be a character’s inner conflict, a societal issue, or a universal human experience. This will serve as the submerged part of your iceberg, invisible to the reader but driving the narrative.

Step 3 | Establish the Surface Story

The next step is establishing the surface story. This is the part of the iceberg visible above the water (the “tip of the iceberg”) and includes the plot, characters, and setting of your story’s world. It should be engaging enough to capture the reader’s attention and subtly hint at the deeper themes underneath.

Step 4 | Develop the Underlying Themes

Now, develop the underlying themes of your story, the vast unseen portion of your iceberg. These themes should indirectly influence the plot and characters, adding depth and complexity to your story without being directly stated.

Step 5 | Use Subtext Strategically

Subtext is a powerful tool in the Iceberg Theory. It’s a literary composition’s unspoken or less obvious message or theme. Use it strategically to hint at the deeper layers of your story, allowing readers to engage more actively with your writing.

Master Hemingway’s Iceberg Theory and story structure

with Celtx’s beat sheets and storyboarding tools.

Step 6 | Practice Minimalism

Hemingway was known for his minimalistic approach. To apply the Iceberg Theory, practice minimalism in your fiction writing. Be concise and omit things, like character backstories, thoughts, feelings, motives, and other “unnecessary” details, allowing the audience to fill in the gaps with their understanding and interpretation.

Step 7 | Show, Don’t Tell

A key aspect of the Iceberg Theory is showing rather than telling. Use descriptive language to show character emotions and plot developments, letting the reader infer what’s happening beneath the surface.

For example, instead of:

Caleb couldn’t wait to get to the beach.

Try:

Caleb’s hands shake, eyes goggle, his mouth wide in a smile.

Step 8 | Master the Art of Omission

Hemingway believed that a writer could omit significant elements of a story, and the audience, if engaged, would feel those elements. Mastering this art of omission lets you leave out explicit information about your iceberg, making your writing more engaging and thought-provoking.

Step 9 | Review and Refine Your Work

Finally, review and refine your work. Ensure that your surface story is compelling, your underlying themes are subtly present, and you’ve effectively used subtext and omission. Remember, like any other theory, the Iceberg Theory requires practice to master. Keep refining your technique with each piece you write.

Why Writers Should Embrace Subtext

The aim of all writers is to tell an authentic and engaging story that reflects our experiences in the real world. Well, in the real world, subtext is all around us in everything we do and say.

If this is the case, then it should be for our characters and the stories they inhabit.

The more our audience can emotionally resonate with our work, the more impact it’ll make on them. We also want to keep our audience engaged at all times, so giving them ample opportunities to work subtle clues out or read between the lines, is crucial!

For more on how you can explore subtext in your work, check out our dedicated blog: Writing Subtext: How to Say More by Saying Less

Conclusion

Mastering Hemingway’s Iceberg Theory allows us to create richer, more engaging narratives.

If we’re able to trust our audiences, use subtext, and embrace strategic omission, we can craft stories that resonate deeply with our readers and viewers.

The most powerful writing isn’t about what’s said but about what’s left unsaid!

Great storytelling happens beneath the surface. Celtx helps you structure your script with tools like beat sheets and automatic formatting, so you can focus on writing with clarity and impact. Give your audience more than what meets the eye—start for free today!

For more on story structure, read these articles next:

- How to Use Ethos, Pathos, and Logos in Screenwriting

- What Is Dramatic Irony? Definition, Examples & How to Use It

- Plot Outline Techniques: How to Structure Your Story for Maximum Impact