Screenwriting is the art of writing scripts for visual storytelling. Film, television, web series, even video games!

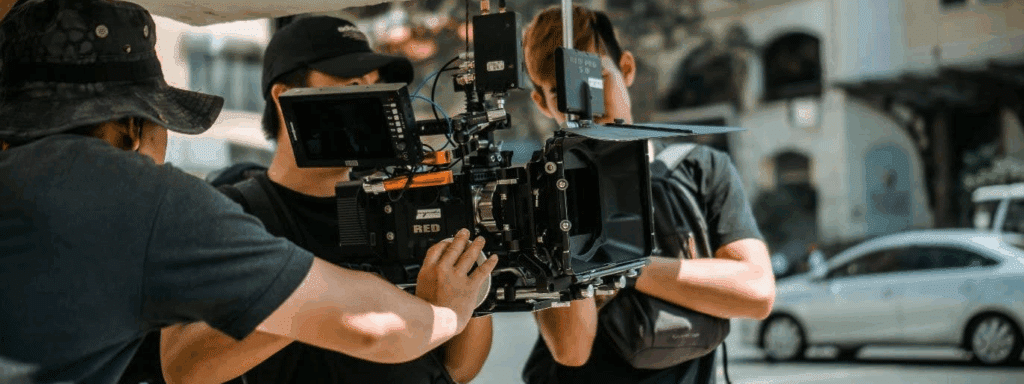

But it’s not just about writing dialogue or describing scenes. It’s about crafting a blueprint for collaboration, a document that guides directors, actors, cinematographers, editors, and designers in bringing a story to life on screen.

Unlike novels, screenplays don’t live on the page. They’re designed to disappear, transformed into moving images, sound, and performance. That’s what makes screenwriting so unique: it’s writing that’s meant to be seen, not read.

Whether you’re a curious beginner or a writer looking to pivot into screenwriting, today’s blog will walk you through the essentials, from formatting to mindset, tools to technique.

So, what are we waiting for?

Table of Contents

- The Purpose of a Screenplay

- The Key Elements of a Screenplay

- Screenwriting vs. Other Forms of Writing

- Screenwriting Software: The Right Tool for the Job

- Story Structure and Genre

- How to Get Started Screenwriting

- The Emotional Journey of Screenwriting

- FAQs

- Conclusion

The Purpose of a Screenplay

Think of a screenplay as an architectural plan. It doesn’t build the house, but it tells everyone how to build it. The screenwriter’s job is to lay out the structure, tone, and rhythm of a story in a way that’s clear, visual, and most importantly, actionable.

A screenplay isn’t the finished product. It’s a starting point, the foundation for a deeply collaborative process. Directors interpret the script. Actors embody it. Cinematographers light it. Editors shape it. And producers make sure it all happens on time and on budget.

That’s why clarity and economy in a screenplay is crucial. Every word on the page must earn its place. You’re not writing prose; you’re writing instructions for a team of creatives to follow.

“A screenplay is not a work of art. It’s an invitation to others to collaborate on a work of art.” – Paul Schrader (Writer, Taxi Driver)

The Key Elements of a Screenplay

Let’s break down the building blocks of a screenplay. These are the elements that make your script readable, scannable, and shootable.

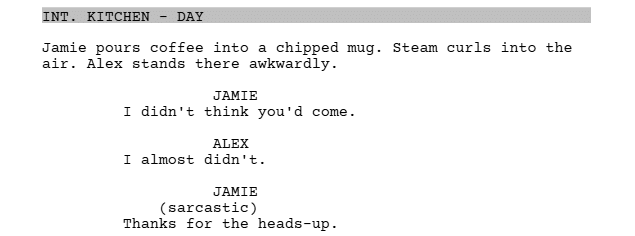

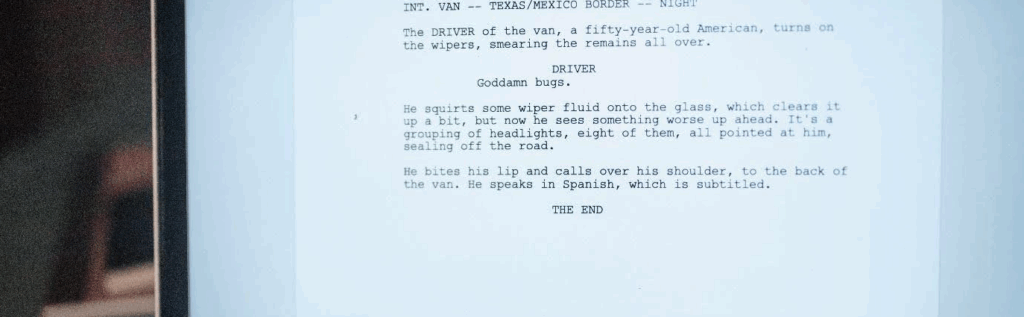

Scene Headings (Sluglines)

These tell us where and when a scene takes place. They’re written in ALL CAPS and follow a standard format.

INT. KITCHEN – DAY

INT. means interior while EXT. means exterior. The location comes next, followed by the time of day. Simple right? But crucial. Scene headings help the production team plan shoots, scout locations, and schedule lighting setups.

Action Lines (Description)

This is where you describe what’s happening on screen. Action lines are written in the present tense and should be visual and concise.

Jamie pours coffee into a chipped mug. Steam curls into the air. Alex stands there awkwardly.

You’re not writing what characters feel, but what the audience sees. If it can’t be filmed, it doesn’t belong here.

Character Names

When a character speaks, their name appears centered and in ALL CAPS above their dialogue.

JAMIE

This helps actors and casting directors quickly identify who’s speaking and when.

Dialogue

This is what your characters say. It should sound natural, reveal character, and move the story forward. Screenplay dialogue is lean, no long monologues unless they serve a purpose.

JAMIE

I didn’t think you’d come.

ALEX

I almost didn’t.

Parentheticals

These are short directions placed under the character’s name to clarify how a line is delivered.

JAMIE

(sarcastic)

Thanks for the heads-up.

Use them sparingly. If the emotion is clear from context, skip the parenthetical.

Let’s see the whole scene put together:

For a full breakdown of screenplay formatting check out our dedicated blog here.

“Ensure that your script is watertight. If it’s not on the page, it will never magically appear on the screen.” – Richard E. Grant (Actor)

Screenwriting vs. Other Forms of Writing

Screenwriting is a different beast from novels, short stories, or plays. Here’s how:

Visual Medium

You write what the audience sees and hears. Internal thoughts? Not unless they’re voiced or shown.

Present Tense

Everything happens now. This keeps the pace active and immediate.

Economy of Language

No flowery prose. Every word must serve the story.

Page Count Matters

One page of screenplay roughly equals one minute of screentime. A feature film script is usually 90-120 pages.

Formatting is Non-Negotiable

Unlike prose, formatting in screenwriting isn’t just aesthetic but functional.

Screenwriting Software: The Right Tool for the Job

While you could write a screenplay in Word or Google Docs, but you’ll quickly run into formatting nightmares. That’s where screenwriting software comes in.

Celtx is a fantastic choice for beginners and pros alike. It’s more than a script editor, but a full production suite. You can:

- Format your script automatically

- Develop characters and story outlines

- Create shot lists and production schedules

- Collaborate with your team in real time

Celtx’s script editor and story development tools are designed to keep you focused on the creative process, not the formatting rules. It’s intuitive, cloud-based, and built for the way screenwriters actually work.

Want to learn more about screenwriting software? Check out our comprehensive guides:

10 Best Free Screenwriting Software Tools

Collaborative Screenwriting Software: Write Together without Chaos

“I want it to be written. I want it to work on the page first and foremost.” – Quentin Tarantino (Writer and Director, Pulp Fiction)

Story Structure and Genre

One of the most powerful tools in a screenwriter’s toolkit is structure. While creativity is, of course, essential, structure gives your story shape. It’s the skeleton beneath the skin.

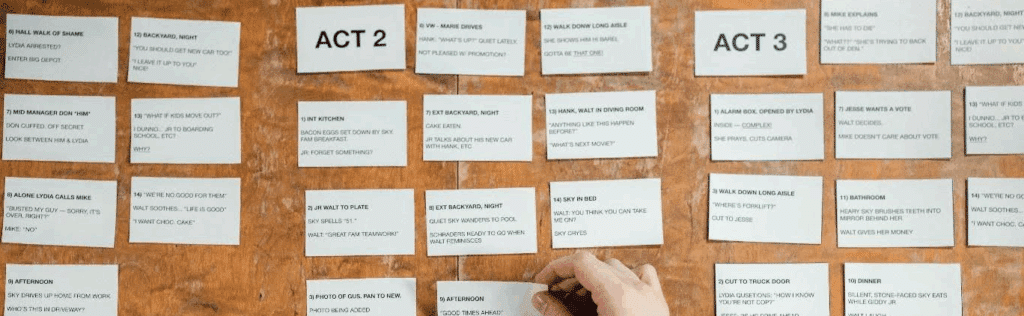

Most screenplays will follow a three-act structure:

- Act One: Introduces your characters, world, and the central conflict. This act ends with a turning point that propels the story forward.

- Act Two: Where your protagonist faces obstacles, makes choices, and grows. This is often the longest act and includes rising tension and stakes.

- Act Three: The conflict reaches its peak and is resolved. Characters change, truths are revealed, and the story finds closure.

Of course, not every story fits neatly into this mold. But understanding structure helps you break it with purpose.

Genre also plays a huge role in shaping your screenplay. A horror film builds tension differently than a romantic comedy. A thriller relies on pacing and suspense, while a drama leans into emotional depth. Knowing your genre helps you meet audience expectations and subvert them in satisfying ways.

Want to write in a particular genre? Then check out our Mastering the Art of Screenwriting series where we take a deep dive in how to write everything from horror to adventure scripts!

“The challenge of screenwriting is to say much in little and then take half of that little out and still preserve an effect of leisure and natural movement.” – Raymond Chandler (Writer, The Big Sleep)

How to Get Started

Okay, so how do you actually become a screenwriter? Here are five practical steps to kick off your journey:

1. Watch Films, But Critically

Pick a few favorites and study them. What’s the structure? How do scenes transition? What’s said, and what’s left unsaid?

2. Read Screenplays

Sites like IMSDb and Script Slug offer free access to professional scripts. Reading them will teach you pacing, formatting, and tone.

And of course, it wouldn’t be a Celtx blog without some recommendations on scripts you should read, especially if you’re just getting started on your screenwriting journey!

Here are five of our favorites:

Parasite (Bong Joon-ho and Han Jin-won)

This Oscar-winning screenplay is a masterclass in tone, structure, and social commentary. It shifts seamlessly from dark comedy to thriller and tragedy, all while maintaining a tight, visual narrative.

The script is also a great example of how to write for a confined space (the house) without it feeling too static.

Read the script here.

The Social Network (Aaron Sorkin)

Sorkin’s dialogue is stuff of legend; it’s fast, witty, and character driven. This script shows how to make a story about coding and lawsuits feel like a high-stakes drama. It’s also a great study in non-linear storytelling and how to weave multiple timelines together.

Check it out here.

Get Out (Jordan Peele)

Peele’s debut screenplay is a brilliant blend of horror, satire, and social commentary. It’s tightly structured with every scene serving a purpose. The script also demonstrates how to build tension through subtext and symbolism.

And here it is.

Lady Bird (Greta Gerwig)

This coming-of-age story is deceptively simple but emotionally rich. Gerwig’s script is a great example of how to write authentic dialogue, develop complex characters, and explore relationships without melodrama.

Read it here.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (Charlie Kaufman)

Kaufman’s writing is wildly imaginative and emotionally raw. This script bends time and memory in a way that’s both surreal and grounded. It’s a must-read for anyone interested in non-linear storytelling and high-concept ideas.

Click here to read it for yourself.

3. Write a Short Scene

Start small. A two-character scene in one location is a great way to practice.

4. Use Celtx to Format It

As we’ve already discussed, let the software handle the formatting so you can focus on the story. Click here to try it for yourself!

5. Get Feedback

Share your work with trusted peers or online communities. Screenwriting is collaborative so start practicing it early.

The Emotional Journey of Screenwriting

While screenplays are a blueprint for a visual story, it doesn’t mean that they’re just technical documents. They’re also emotional. You’ll wrestle with self-doubt, face rejection, and rewrite until your eyes blur.

But you’ll also experience moments of pure creative joy, and that’s the magic of screenwriting!

Remember, it’s okay to feel stuck and to take breaks. Screenwriting is a marathon, not a sprint and the most important thing is to keep going.

And you’re not alone. Every screenwriter has stared at a blank page wondering if they’re good enough. You are. Your voice matters, and your stories matter.

FAQs

In most contexts, they’re interchangeable. But sometimes “scriptwriter” refers to someone who writes for non-film formats like radio, corporate videos, or instructional content. “Screenwriter” typically means someone writing for film or television.

Novels explore internal worlds. Screenplays externalize everything. You can’t write “She felt anxious”, you must show it. Maybe she fidgets, avoids eye contact, or checks the time obsessively. Screenwriting is about behavior, not introspection.

– Develop compelling characters and story arcs

– Write visually and concisely

– Revise based on feedback

– Collaborate with directors, producers, and other creatives

– Sometimes pitch or sell your script

Nope. Plenty of successful screenwriters are self-taught. What you do need is persistence, curiosity, and a willingness to rewrite. That said, screenwriting courses and degrees can offer structure, mentorship, and networking opportunities.

Conclusion

Screenwriting is a rewarding blend of technical skill and creative instinct. It’s about crafting stories that move people, literally and emotionally. You’re not just writing words; you’re building worlds, shaping performances, and guiding entire productions.

The right tools can make all the difference. Celtx’s all-in-one workflow helps you move from script to shot list to production schedule in one place. It’s built for storytellers who want to stay focused on the story, not the formatting.

Now that you know what screenwriting is, the only thing left to do is start.

So what are you waiting for? Try Celtx for free today!

Up Next:

How to Write a Script: From Idea to Screenplay

Now that you know what screenwriting is, it’s time to start your own. Learn the essentials of how to write a script and bring your ideas to the page.