We all love a montage. Fast-paced, music-backed sequences that zip through time. From boxers getting in shape, couples falling head over heels in love to someone turning their life around, a well-done montage can say a great deal without any dialogue.

While montages are one of the must fun and powerful filmmaking tools, writing one can seem like a whole other ball game. Well, if you’ve ever stared at your script wondering how on Earth you’re going to nail montage formatting, you’ve come to the right place!

In today’s blog, we’re diving into all there is to know about how to write a montage, when to use one, how to format it and make sure it reads clearly.

In short, Celtx is here to take the mystery out of montage formatting.

FADE IN:

In This Article

- An Introduction to Montage Script Format

- When to Use a Montage in Screenwriting

- How to Format a Montage in a Script

- Single Location vs. Multi-location Montages

- Series of Shots vs. Intercut

- Montage Examples in Film

- Celtx Formatting Tips

- Conclusion

An Introduction to Montage Script Format

In terms of a screenplay montage, it conveys a particular passage of time, including multiple events, character perspectives and emotions quickly.

Montages usually fall into one of three categories:

- Linear montage

- Thematic montage

- Emotional montage

Linear Montages

Linear montages visually show chronological progress over time, with each shot building on the last. They’ll usually follow characters on a journey, learning a new skill, preparing for something big, or completing a task that takes time and effort.

Thematic Montages

A little more of an artistic montage, these are a collection of shots that are all connected by a central idea, mood, or topic.

For example, characters could be reacting to the same event, or characters from different walks of life could be shown doing similar things. Thematic montages are all about patterns, contrast, or commentary as opposed to a timeline.

Emotional Montages

These dig deep into what’s going on internally within a character. They could show memories, fantasies, fears or emotional shifts. We see flashes of their past, visions of what could be, or symbolic visuals that reflect how they’re feeling.

When to Use a Montage in Screenwriting

So now we know the different types of montages we can use, exactly when should we use them in our scripts?

The short answer is they shouldn’t be the easy way out or function as fillers within your story. All montages should serve a narrative function. If they don’t, they’ll need to be binned!

Here are five circumstances where montages can work well within a screenplay:

1. Condensing Time

If you want to show a process such as training, researching or traveling that unfolds over hours, days, or weeks, then a montage could work to speed things up and provide the audience with the exposition they need in little time. The story is then able to move on quickly and keep pace.

2. Illustrating Growth

When a character undergoes a physical, emotional or professional change, and you want to show this in an efficient way within the script.

3. Introducing a World

This works especially well in sci-fi and fantasy where you’re establishing a whole new world to the audience. If you’re looking to show how a new environment works and its rules, montage can work well.

4. Juxtaposing Events

If you need to show multiple storylines unfolding simultaneously, a montage could be your new best friend.

5. Enhancing Emotion or Tone

A montage evoking joy, tragedy, or chaos can heighten a scene’s emotional impact and drive the story forward.

Avoid montages altogether if key dialogue or exposition is needed as a montage may just obscure things. Think of montages as supplements, not substitutes, for storytelling.

How to Format a Montage in a Script

You may already be aware of screenwriting formatting conventions and how important they are in ensuring your script is up to industry standards, from title page to FADE OUT. When it comes to montage, it’s no different.

There are several ways to format a montage:

Standard Montage Format

Start with a scene heading to indicate that a montage is beginning. Then use bullet points to describe each frame.

INT. GYM – DAY

MONTAGE – JIM’S TRAINING

-Jim does one-arm push-ups

-Jim sprints up a hill

-Jim punches the heavy bag with increasing speed

-Jim runs up the museum steps and throws his arms up

END MONTAGE

Formatting a training montage like this keeps everything under one heading. This works particularly well when each shot is brief and don’t need separate scene headings.

Scene Headings for Each Shot

Your montage may need more detailed visuals or to span several locations. Never fear, as you can write out each as its own scene.

Make sure to introduce the sequence as a montage first before diving in, like this:

MONTAGE – JANE PREPARES FOR THE INTERVIEW

INT. BEDROOM – DAY

Jane tries on several different outfits.

INT. KITCHEN – LATER

Jane spills coffee on her shirt.

INT. SUBWAY – LATER

Jane reviews interview questions on her phone.

END MONTAGE

This method of montage formatting allows you to have a little more control over the visuals and pacing. We still have a clear understanding of each shot and where they take place.

In line with Parentheticals

A less-common method of formatting montage, it is most useful when writing dialogue-heavy scenes. Here, parentheticals intercut with voiceover narration can help to contextualize what’s happening on screen.

BOB (V.O.)

(while we see a montage of him preparing)

I woke up at 5am, ran three miles, drank a protein shake, and prepped by slides.

There is no right or wrong way to write a montage; it’s completely up to you and what suits your writing style. Pick the technique that works best for you and best conveys the montage’s message. If your script has several montages, make sure you are consistent in how you format each one.

Want to refresh yourself on screenplay formatting conventions? Take a look at our Script Format | A Beginner’s Guide to Screenplay Writing article.

Formatting a montage?

Celtx script writing software makes it easy with smart tools built for screenwriters.

Sign up and get started!

Single Location vs. Multi-location Montages

Montages don’t always need to occur in just one location. Often, they’ll span multiple settings. Single location montages are simpler to format as we saw above with Rocky’s training program taking place in the gym, with bullet points depicting each shot.

Multi-location montages are where things become a little more complicated, and where you’ll need to ensure your reader doesn’t lose track of where they are. As with the single location montage, it’s important to include brief visual details of each shot, but you have several options as to how to format it.

Indicate Location Changes with Slug Lines

You can indicate a change of time and place with a brief slug line.

Use Separate Paragraphs

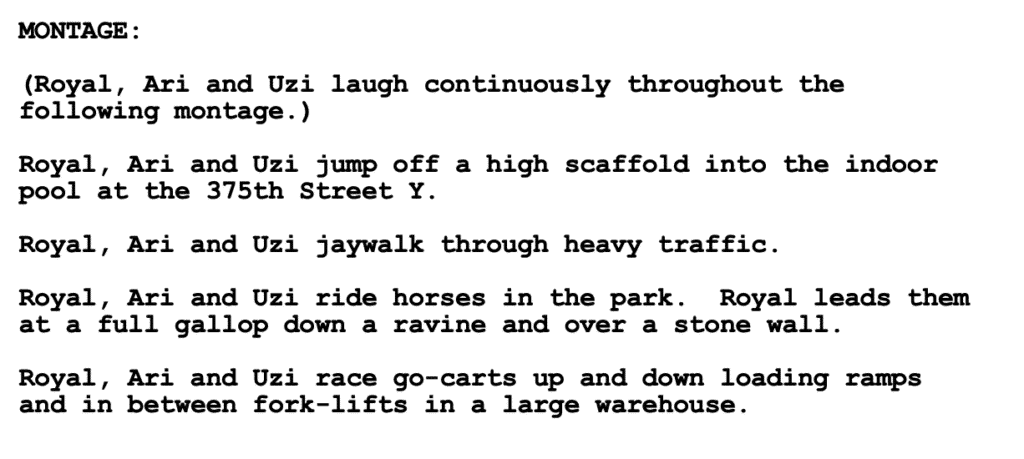

Simply start a new paragraph once you change time and place, adding the details into the body of the paragraph itself, as shown in Wes Anderson’s and Owen Wilson’s screenplay The Royal Tenenbaums.

Use a Bullet Point or Dash List

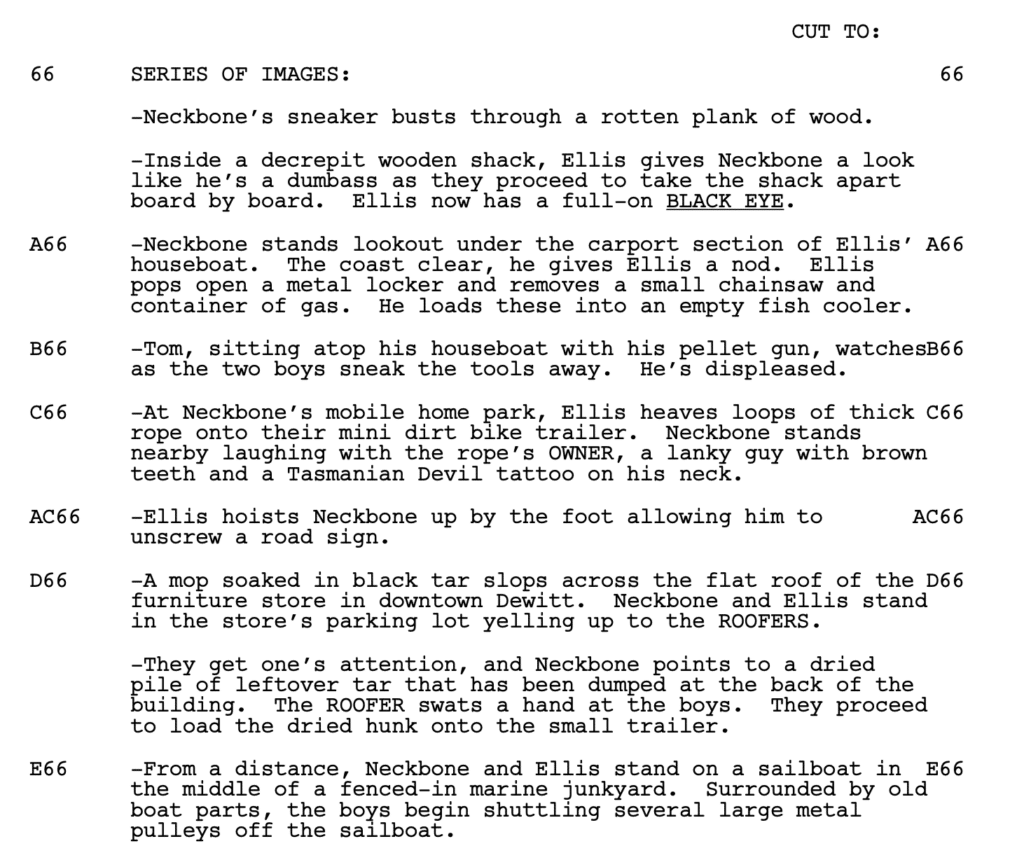

Or in the place of paragraphs, use a bullet-style or dash list to show each new location. Again, you’ll need to detail the location into the body of each point. Notice how Nicholls has broken up the shots in the screenplay for 2012’s Mud.

Series of Shots vs. Intercut

With so many pieces of screenwriting terminology flying around, it’s easy to confuse montages with similar devices like ‘series of shots’ or ‘intercut’.

So, let’s waft away the confusion and explore how they differ.

Series of Shots

These are generally a lot quicker paced that a montage and often lack the transformational arc that a montage gives us. For example:

SERIES OF SHOTS – BOB MAKES BREAKFAST

– Cracks eggs into a pan.

– Toast pops out of the toaster.

– Coffee brews

Notice how nothing groundbreaking happens, it’s just a device that moves the story on, so we don’t have to watch Bob spend twenty minutes preparing his breakfast.

Intercut

These are used to show two or more scenes unfolding simultaneously, often cutting back and forth. Intercuts are perfect for things like phone conversations or showing scenes with characters in two different locations.

INTERCUT – JACK IN NYC/GRACE IN LA

– Jack packs a suitcase

– Grace books a flight

– Jack grabs his passport.

– Grace grabs her sunglasses.

Montage Examples in Film

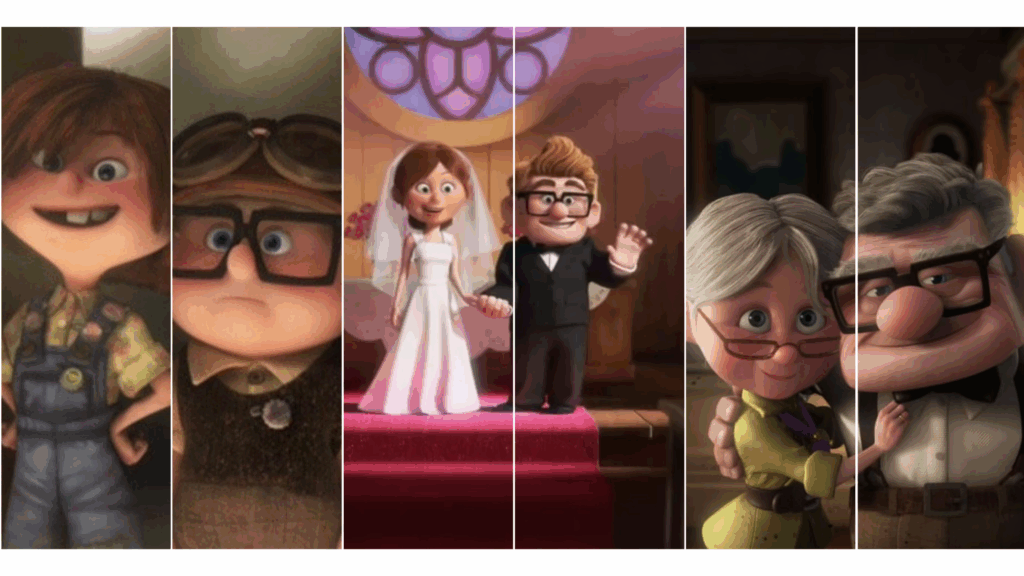

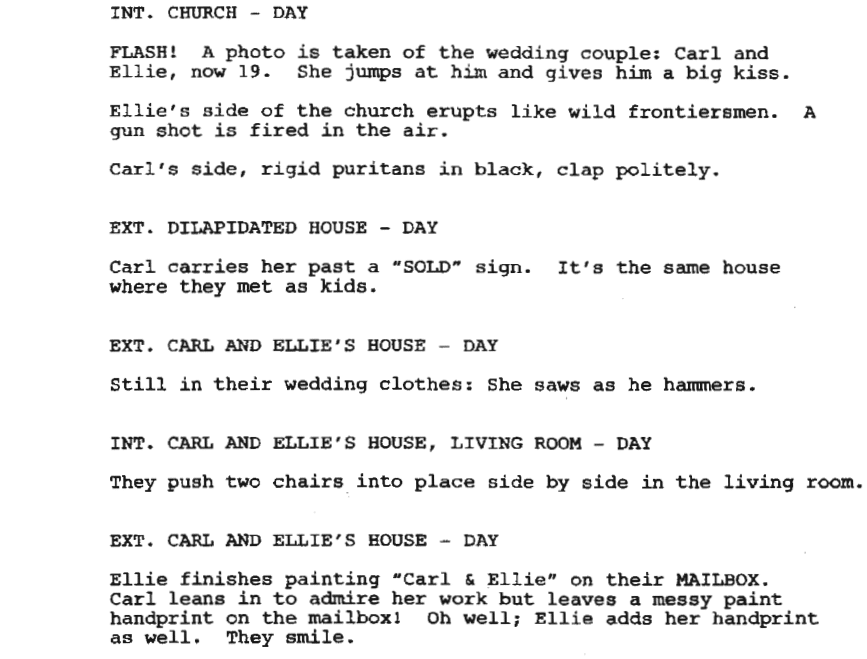

Case Study #1 | Up (2009)

Probably the most famous montages in recent movie history is the opening scene of Disney Pixar’s Up, where we are introduced to Carl and his relationship with Ellie, ending on a heartbreaking note. It’s from here we pick up with Carl’s individual story and how he copes with losing the love of his life.

In the instance of Up, montage is used to show the span of Carl and Ellie’s life together, encompassing decades of time. There are other purposes to a montage, such as showing a character moving from one location to another, or to reveal details about a world, the repetitiveness and mundaneness of life before a life-changing inciting incident. The list goes on.

Here’s a snippet of the montage from the original screenplay so you can see how it was formatted.

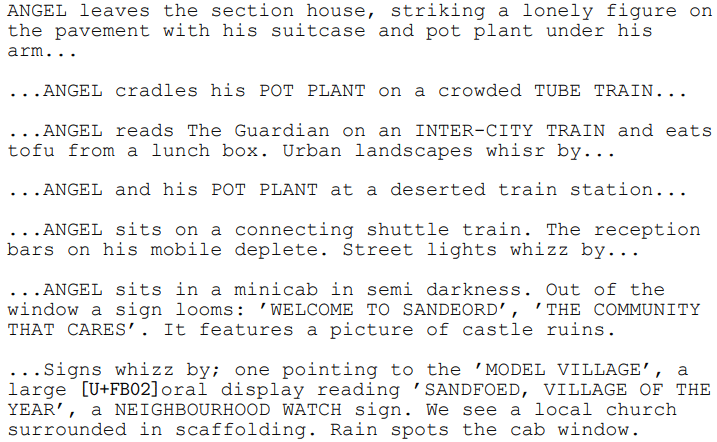

Case Study #2 | Hot Fuzz (2007)

Just leave it to Simon Pegg and Edgar Wright to make the most boring tasks look like an action sequence! In this montage, Nicholas Angel is being transferred to his new police department which of course requires many mundane elements.

The montage tightens this up with elements of parody and style.

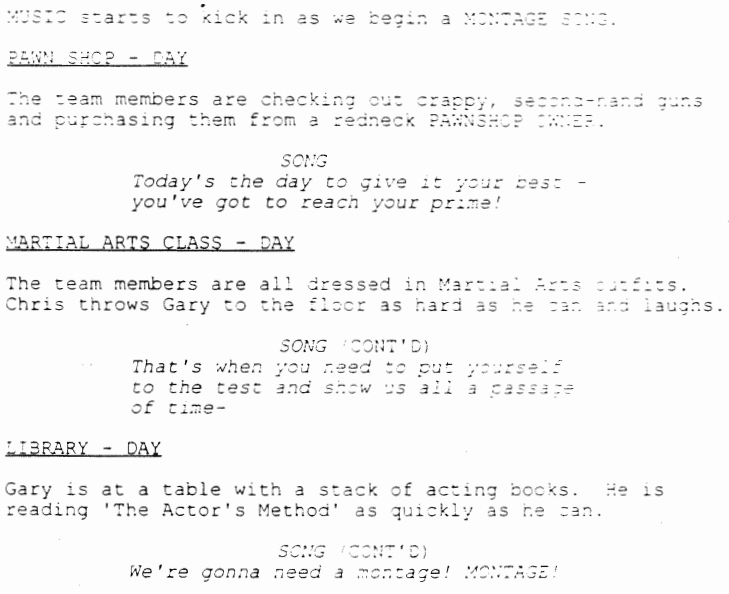

Case Study #3 | Team America: World Police (2004)

This seems like an Inception kind of thing: a montage within a montage. A satirical take on every overused training sequence in action movies. We’re even treated to a song all about montages which plays into the trope and almost ridicules it, but in the best ways.

Case Study #4 | Moneyball (2011)

There are many montages in this movie but the standout one is when Billy and Peter start reshaping the baseball team using stats, all tied together by fast cuts and snappy dialogue.

It’s hugely effective as it condenses a massive amount of strategic decision-making into one impactful sequence.

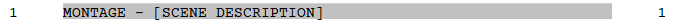

Celtx Formatting Tips

As always, Celtx’s comprehensive screenwriting software is here to automatically format your script. However, there are a few things you can do to make the process seamless.

1. Use Scene Headings

Label the scene like this using the SCENE HEADING element in Celtx.

2. Action Elements

For each moment of action, use bullet points in the ACTION element to describe them. Press ENTER to create new actions.

Here we see the transformation in Emily as she struggles preparing for the audition but then ends up succeeding. This is a very basic example but gives you an idea on how the format should work.

3. Tag Elements

Celtx also allows you to tag characters, props, and locations to make formatting your montages even easier.

Check out how to break down and tag your script here.

4. Keep it Simple

Remember clarity is the key when it comes to montage. Don’t get overly poetic and let the visuals do the heavy lifting!

Conclusion

Montages are powerful storytelling devices that can condense time, heighten emotion, and enhance your script’s visual rhythm. But to be effective, they must be both purposeful and well-formatted.

By mastering montage formatting, you’re adding a high-impact tool to your storytelling arsenal. So, write that training sequence, falling-in-love arc, or epic travel montage. Just make sure it earns its place in your screenplay.

Montages may jump through time and space—but your formatting doesn’t have to.

Celtx screenwriting software keeps your structure solid.

Start your free trial today.

For More on Script Format:

- How to Format Your Screenplay Title Page [5 Easy Steps]

- How to Format a Script | A Step-by-Step Guide

- What are Parentheticals? [When, How and Where To Use Them]