Introduction

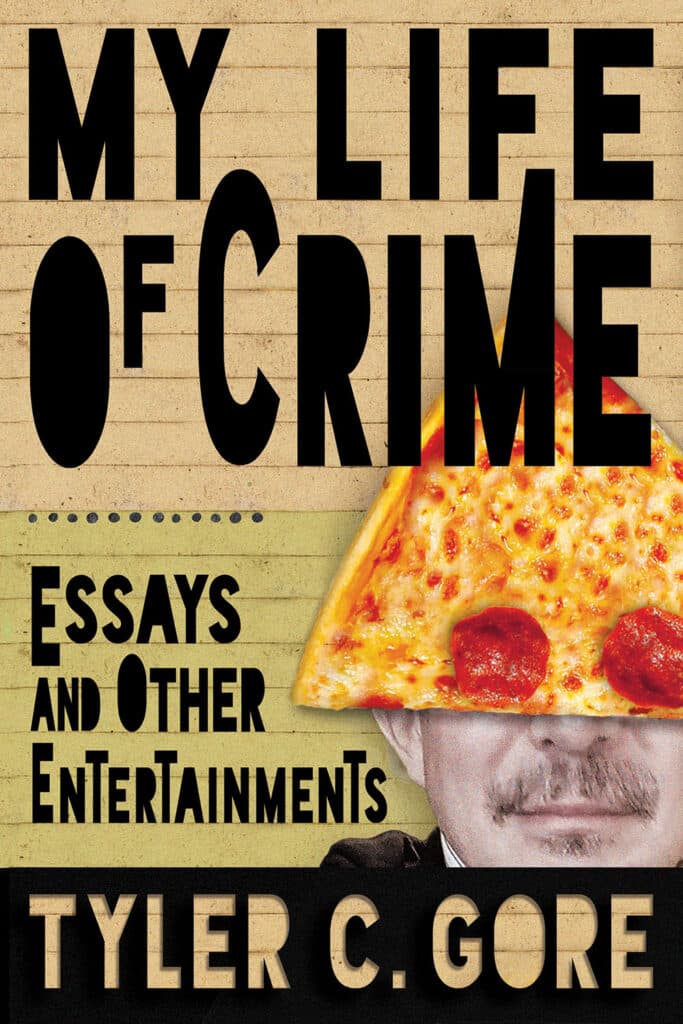

If there’s one thing Tyler C. Gore understands, it’s that humor lives in the details of everyday life. A five-time Notable Essayist in The Best American Essays, a Fulbright Scholar, and a long-time creative writing teacher, Tyler brings both wit and wisdom to his work. His debut book, My Life of Crime: Essays and Other Entertainments, guides readers through quirky, relatable, and often hilarious experiences—from New York City’s unpredictable subway encounters to the mystery of a misplaced sandwich.

Tyler was kind enough to sit down and let me pick his brain about his journey into writing, his distinct view on life’s absurdities, and how he masterfully turns the mundane into comedy gold.

Here’s our conversation with a storyteller who finds joy in both the chaos and beauty of New York City, inviting us all to find humor in the unexpected.

Celtx: Tell us about you—what path in your life do you think brought you to where you are today?

Tyler: Poor judgement, mostly.

But as to why I write… well, my mom taught me how to read when I was only around three, and thus I became addicted to books at a tragically young age.

Parents with young children should take note: Reading is a gateway drug, and if you’re not careful, you might accidentally turn your kid into a writer.

You write both fiction and nonfiction. Do you find the process of writing those completely different?

My Life of Crime is a collection of personal essays—memoirs, really—and that kind of narrative nonfiction shares a lot of qualities with fiction. You are telling a story. Characterization, pacing, tone, and plot are all important considerations.

But there are significant differences, too.

In fiction, you have no obligations to the real world: Your primary job is to make the reader believe in the reality you have created on the page. So if you’re a convincing enough storyteller, it’s totally fine if your central character is a halfling recruited by a wizard to journey across the world to drop a magic ring into a volcano. Throw in some elves and a talking tree and call it a day.

In memoir, your stories are drawn from real life, so the events and characters are supplied by your own experience. That sounds a lot easier, but it isn’t. Our actual, nonfictional lives are messy, with lots of intersecting stories happening at the same time, too much of everything going on all at once. Your job as a personal essayist is to weave a story out of the raw, undifferentiated moments of ordinary experience.

You have to figure out what fits into the arc of the story you’re telling and cut out the rest.

In your non-fiction writing, you certainly don’t seem to hold any truths back (which I appreciate). Do you ever get nervous about “oversharing”?

Oh, definitely! When my wife gave her mother a copy of My Life of Crime, I prayed that she’d never actually read it. (I haven’t dared to ask.)

But you know, there’s a kind of illusion at work here.

I often think of the old-school burlesque dancers —you know, with the sequins and the ostrich feathers. Their art was to make you think you were seeing a lot more than you actually were.

So a certain amount of calculation goes into which mortifying details of my life I’m willing to reveal. More than most people, perhaps. But not everything. You don’t get the full monty.

The hardest part about writing memoir is other people. It’s one thing to write about your own embarrassments, faults, and personal failings. It’s quite another to expose the people in your life to that kind of public humiliation. I’ve found little ways around that, to disguise or muddy the identifying details, but still—there are lots of things I’d never write about because they might embarrass someone I care about. It’s nice to have friends.

From one non-fiction writer in the “humor” category to another, I get asked more often than I’d like why I don’t do stand up comedy. What is it that makes you put pen to paper as opposed to trying out the stage?

Of all the arts—outside of tightrope walking—stand-up comedy is surely the most brutally terrifying. It requires incredible bravery. It’s no coincidence that comedians talk about “dying” on stage.

An actor can give a terrible performance and the audience will still politely applaud at the end. But no one fakes laughter. And when people pay good money for you to make them laugh, they tend to get pissed if your jokes don’t land. Stand-up is pretty much the only performing art where it’s perfectly acceptable for the audience to boo and heckle the performer they paid to see.

It’s a lot safer sitting behind a keyboard.

If someone doesn’t like my book, the worst outcome I’m going to face is a shitty Amazon review. They aren’t going to show up at my apartment and jeer me at my desk. Well, I hope not, anyway.

That said, I actually really love doing readings, particularly when I’m reading humorous material. Making an audience laugh really is an intoxicating thrill. Better than drugs or sex. Because, after all, no one fakes laughter.

But even with those public readings, I don’t face the same kind of pressure to be funny as a comedian would—because I’m not a comedian. I’m not writing a series of bits and punchlines where the audience is expected to burst into laughter every few minutes. That’s not what my work is about.

Most of my personal essays could accurately be described as comedies—albeit bittersweet ones—but not everything in those stories is supposed to be laugh-out-loud funny. What I’m shooting for is that I’ve told you a well-written, engaging, entertaining story about my life, one that will stay with you long after you close the book.

The best stories—fictional or nonfictional—broaden our understanding of what it means to be human. Achieving that is far more important to me than having every joke land.

How do you know when you’ve crafted a story that is genuinely funny? Is there something that clicks for you, or do you just put it all out there and let people make up their own minds?

It’s always hard to know for sure if you’ve written something other people will find funny. What I shoot for is that I find it funny. What’s funny is often rooted in the element of surprise—an unexpected phrasing or punchline, for example—so the ideal situation is when I manage to surprise myself with some clever line that I hadn’t had in mind at all. And yes, there is a kind of click when you know you’ve come up with the perfect line. It can take a while to get there, but sometimes it just magically happens.

But I also have an imaginary audience in mind. Certain very funny friends who always make me laugh. It’s a badge of pride if I can make them laugh, so sometimes when I’m writing, I think: would this make them crack up?

And my wife Leigh—AKA “Natasha,” as she’s called in My Life of Crime—is almost always my first reader. She has a great sense of humor. If she finds it funny, it stays in for sure. It’s the best feeling in the world if she’s reading a draft of mine and suddenly bursts into laughter.

If you could take one of your essays and adapt it into a movie, which would it be?

I’ve always thought “October’s Rain” —the most lyric essay in the collection—would make a lovely animated short, although one that would probably rely on a narrative voiceover.

“Clinton Street Days” —which recounts my youthful adventures in the East Village—would certainly offer an array of fascinating characters and settings.

But if I had to choose just one, there’s no contest: “Appendix,” the novella-length essay that takes up the last two-thirds of My Life of Crime. I’ve actually had several people tell me they thought it would be perfect for a movie or limited television series.

Why?

Well, for starters, “Appendix” offers a full range of emotional complexity. Sure, it’s very funny—at least I hope it is—but there’s a lot more going on than just that.

“Appendix” is ostensibly about the events surrounding my “routine” appendix surgery in January 2016—just two weeks of my life—but it’s also really an encapsulated portrait of the artist.

My somewhat disheveled life in Brooklyn with my wife Natasha, our crummy apartment building, our devotion to our ferocious and occasionally anorexic cat, Luna—and, of course, all the terrifying comedy that unfolds the minute you step into a hospital emergency room.

Who would play you?

Huh, interesting question! I’ve genuinely never thought about that before.

Well, we look nothing alike, but I think Steve Carell would be a great choice. He’s terrifically funny but he’s also a nuanced and versatile actor who’d be more than capable of bringing the right combination of pathos, comedy, whimsy and heartbreak to the role.

We often ask people for the BEST writing advice someone has ever received, but with your experience as not only a creative writer, but a teacher of creative writing, what do you think the WORST advice is out there for aspiring writers?

I suppose this is heretical, but I’m often irritated by those two sacred directives that are trotted out in almost every introductory writing manual: “Show, don’t tell” and “Write what you know.”

My problem with “Show, don’t tell” is the implication that “telling” is something you should never do in a story, which is ridiculous advice that you will find routinely ignored in just about every great work of literature. Exposition, narration, authorial asides, backstories, and summarized lapses in time are all forms of “telling” that can be highly effective in a story or novel. Take a look at Wuthering Heights, for example, where so much of the power of that novel lies in the elliptical way that story is told.

So my version would be “Learn when to show, and when to tell.” Not as snappy, but not as misleading either.

Ok, on to the other one: “Write what you know.” So this one is really aimed mostly at fiction writers, since in nonfiction you are, by definition, already writing what you know.

In fiction classes, “Write what you know” often results in Story about a struggling writer who hates her day job. Stories limited to the writer’s everyday experiences, characters too closely modeled on the kinds of people that the writer knows in real life. Often this is boring material, even for the writer herself.

Fiction is about imagination. I think the kernel of wisdom behind “Write what you know” is that you can draw on your own life experiences and emotions to bring depth to your fictional characters and the imagined world they inhabit. That doesn’t mean that your fictional world has to resemble your real life. If all fiction writers limited themselves to their actual lives, we’d never get to read about hobbits or time machines. We’d never get Gregor Samsa, the Cheshire Cat, or the Ghost of Christmas Past.

Better, I think, is the famous line attributed to the Roman playwright Terence: “I am human; nothing human is alien to me.”

Draw on your human experience to create characters who are different than you—or even nothing at all like you— to create worlds which do not resemble your own, but which nonetheless have their own internal logic and are terrifyingly real to the characters who live inside them.

What do you notice creative writing students struggle with the most, and how do they overcome it?

Although the workshop model—in which students bring in their work for critique by their peers—creates a sense of community and offers writers a peer group of invested readers, it can also sometimes result in what is pejoratively known as “workshopped writing”: pieces that are polished and well-written, but which take no risks.

I think this is just a baked-in hazard of the workshop model. Every week, it’s your responsibility to critique a manuscript written by one of your classmates, and that puts you in the position of having to find something to critique. What works in this story, what doesn’t work? You are a hammer looking for a nail. So anything that sticks out – an odd, unexplained detail; an implausible circumstance; an idiosyncratic way of phrasing something—tends to be the easiest thing to focus on when writing feedback. And so the writer can come to think that anything weird or peculiar should be excised, sanded over. The unintended lesson is don’t stick your neck out.

But the idiosyncratic quirks that a writer brings to her story—those odd nail heads jutting out of the work, begging for a hammer—often supply the crucial difference between good writing and great writing. In truly brilliant work, the faults and virtues often hang together as a inseparable whole, the result of a singular mind struggling to express an unexpressed vision. Take a moment to imagine Melville submitting chapters of Moby-Dick to a workshop, and you’ll see what I’m getting at.

To be sure, getting a second pair of eyes on a piece can be very useful. When you’re knee-deep in the weeds, it can be difficult to understand the shape of your own work, how it will be experienced by readers. But it’s also crucial not to let the opinions of others derail your own vision of the work. You’re already going to be struggling with your own inner critic.

It is very difficult to turn off your inner editor while you are composing. This is a lifelong battle every writer faces on a daily basis. You have to learn to let the page write itself. It often refuses to do so until you get out of the way.

How to exactly to do that—to get out of the way— is a long process of self-discovery. Only you can write the way you write, and you want to allow the writer inside you to develop and flourish.

So listen to what your fellow workshop readers have to say attentively—they’re your fellow writers, and many will undoubtedly have thoughtful, useful insights—but with a light spirit. Take everyone’s advice with a huge grain of salt. It’s your work, not theirs.

Don’t be afraid to have fun. Let your freak flag fly, and learn to trust your own process.

Tell us about “My Life of Crime” – what inspired you to put together your essays spanning decades of your life?

From a publishing perspective, My Life of Crime is such a weird collection.

You get eight short personal essays, which cover such diverse topics as my sordid past as a prankster, my disappointing visit to a nude beach in Fire Island, and my family’s struggles with hoarding.

Taking a sharp left turn, you then encounter three gonzo absurdist “entertainments,” which includes a recipe for “Deep Fried Cheezy Snacks.”

And finally—when you’re barely a third of way through the book—you come upon “Appendix,” a freewheeling, roller-coaster account of my “routine” surgery that serves as a springboard to discuss mortality, evolution, parallel universes, W.B. Yeats, and Regina Spektor.

Here’s how this strange arrangement came about:

Over the years, I’d been publishing short personal essays in various periodicals and reading them in public. Jacob Smullyan, the founding publisher of Sagging Meniscus Press, was a fan of my work and asked me if I’d be interested in putting together a collection of my personal essays. “Definitely!” I told him, “But I’ve been working on this essay about my recent appendectomy, and I’d like to include that in the collection.”

So I sent Jacob some pages from my draft, and he was enthusiastic and told me to keep working on it.

At the time, I’d expected “Appendix” would run about 20 pages or so, about the length of “Clinton Street Days” or “Stuff,” two other essays in the collection.

But that’s not what the story wanted to do. It wanted to be expansive, divergent, multi-faceted. It wanted to have snarky footnotes. I tried to get it to stop doing all that, but it kept insisting. Eventually, I let it go where it needed to go, and “Appendix” bloomed into novella-length juggernaut. The published essay is almost 200 pages long, and took me almost two years to complete.

“Appendix” had a complicated timeline that needed to be shaped into a coherent story with recurring themes and a satisfying emotional arc. It’s difficult to do this when you are working with real events. That was all a learning experience for me, a lot of trial-and-error, a lot of revision.

Thankfully, Jacob was incredibly supportive during this whole process, even during those times when I despaired that I’d never finish.

“Appendix” really could have been published as a separate book, but I’m very pleased with how it works with the rest of the collection. Taken as a whole, My Life of Crime is a kind of portrait of New York City, a love letter to the exasperating, exhilarating town I’ve called home for nearly my entire adult life.

Where can people who want to support and follow along with your journey find you?

My website is https://tylergore.com, and there’s a contact form there if you’d like to get (very) occasional updates, or just to get in touch with me. I’m also on most social media platforms— Facebook, Instagram, Twitter.

You can buy My Life of Crime from Amazon (where it is also available as an e-book) or any online bookseller. (Or just ask your local bookstore or library to order it!)

Conclusion

Tyler’s reflections remind us that the best stories often lie in life’s odd, unpredictable moments. With years of experience teaching creative writing, he brings profound insight into the craft, offering advice that any writer — new or seasoned — can benefit from. Whether he’s recounting family quirks or philosophizing about hospital visits, Tyler reveals the comedic gems in everyday life. For anyone who could use a laugh — and some refreshing honesty — My Life of Crime is a must-read. It’s an invitation to see life’s twists with a smile and turn your own “life of crime” into stories worth sharing.

If you loved Tyler’s perspective, try these interviews next:

- Interview: Umar Turaki On Filmmaking, Writing, and His New Novel

- From Tunes to TV: An Interview with Comedy Writer Trevor Risk

- Celtx Spotlight: Director, Writer, and Producer Brandon Champ Robinson