You just can’t stop that killer movie idea darting around your mind, just refusing to go anywhere. It’s time to put your ideas onto paper (or screen) and start writing your screenplay. This can be a formidable prospect at first, especially when it comes to the many screenplay formatting rules.

Here at Celtx, we’re here to dispel the thinking that screenplay formatting has to be complicated. Once you’ve armed yourself with standout screenwriting software, and have mastered the basics, you’ll be free to spread your creative wings, and write your script.

So, let’s explore the conventions of screenplay formatting and how you can ensure your work is written to industry standards.

Table of Contents

- What is a Screenplay?

- Why is Screenplay Formatting So Important?

- Screenplay Formatting Standards

- Screenplay Element Categories

- Writing a Screenplay

- FAQs

- Conclusion

What is a Screenplay?

A screenplay is a document which scripts a movie, or TV pilot. It includes details on the visuals that the audience will see on screen, as well as the accompanying dialogue spoken by the characters.

Screenplays can vary in length, with short films starting at 1 page, all the way to 30 pages. TV pilots can be anywhere from 25 pages to 60 pages, and feature-length movies from 70 to 180 pages (most movies will be around the 110-page mark.

We’ll discuss page counts and time frames later in the article.

Why is Screenplay Formatting So Important?

It’s common to consider screenplay formatting as pernickety and unnecessary, a way to stifle the creativity in screenwriters. In reality, formatting has a crucial role to play in the overall filmmaking process.

It is important to note that filmmaking is a collaborative art, with the script being the blueprint. All departments from the director to special effects will need the script to do their job to the best of their ability, so it needs to be consistent in its format to be understood and interpreted by everyone.

Film budgets and shooting schedules also rely heavily on the script. Without it, films can spend too much money too quickly, jeopardizing the production.

Screenplay Formatting Standards

Font

We all have our preferred fonts when it comes to writing. Whether you are a traditional Times New Roman enthusiast or prefer more modern fonts like Arial or Calibri, fonts and their size can shape how we write and our enjoyment of writing.

When it comes to screenplays, there is a standard font and size. All use Courier font style, at size 12-point. The reason the same font is consistently used in the industry, is to make it straightforward to ascertain an estimated screen time based on the number of pages written.

It may be tempting to use your preferred font, but do not give in! If you do, your script will come across amateurish and will be tossed aside almost immediately, even if it is the next blockbuster hit.

Margins and Spacing

Another factor that contributes to the page count and screen time estimation are the margins and spacing between the elements on the page.

- Left-hand margin: 1.5 inches (to leave space for the screenplay binding once printed)

- Right-hand margin: 1 inch

- Lines per page: 55

- Character names: Uppercase and start 3.7 inches from the left-hand side of the page.

- Dialogue lines: Start 2.5 inches from the left-hand side of the page.

- Page numbers: Top right-hand corner, 0.5 inches below the top of the page (note that the title and first pages are not numbered).

With the evolution and constant development of screenwriting software, it is not necessary for you to manually apply these formatting conventions yourself, however, they are always useful to keep in mind.

Script Length & Page Counts

As mentioned previously, screenplay lengths can vary based on the type of project and even the genre, with most comedy movies sitting around 90 pages, and the action/drama genres at 110 pages.

A general rule of thumb is that one page of script roughly equals one minute of screentime. So, 90 pages is around one hour and a half, and 110 pages is around one hour and fifty minutes.

That does not mean you have to aim for these run times, as it’s more important your screenplay is as lean and compelling as possible. You want to keep your audience always engaged.

Screenplay Element Categories

Start and End of Act

Structure is crucial in any screenplay, ensuring you are hitting the right plot points at the right time. It isn’t necessary but can be beneficial to separate your script into acts, especially if you’re writing for television.

For example, most comedy shows will have a teaser (one to two pages), followed by three to five acts. To separate the acts, type in the name of the act at the beginning of your script and underline it.

Let us look at our script example to show how this would be formatted.

At the end of the act, click on NEW ACT in your chosen screenwriting software and it will automatically start a new page, clearly showing the separation:

Scene Headings

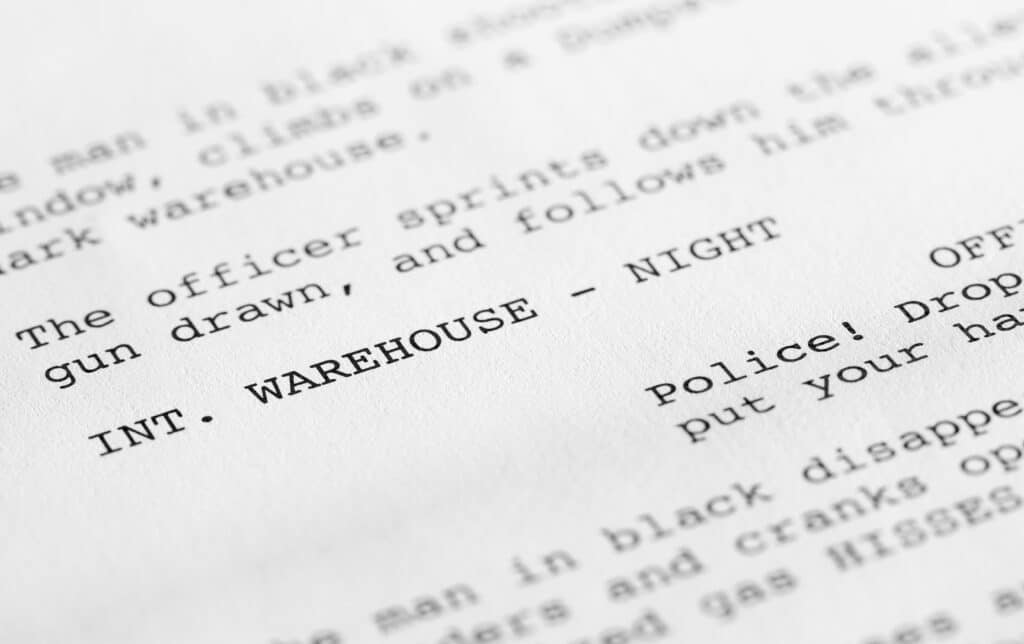

Scene headings contextualize a scene, placing us exactly where and when the action is taking place. It tells us a location, and then a time frame. They are always capitalized to clearly earmark where a new scene begins.

You will see that our scene is outside (EXT. for external) and is set on a BEACH in the DAY time.

When you’re writing your own scene headings, also known as sluglines, you’ll first need to establish whether it’s taking place internally (INT.) or externally (EXT.), before adding the location, and then the time of day (day, night, morning, evening etc.).

If a scene directly continues from the previous scene, you can use continuous (CONT.) to highlight this.

Or, if the new scene is happening shortly after, you can use MOMENTS LATER.

Some movies will have scenes taking place in cars or other moving vehicles. In this instance, some of the scene will take place internally, and some externally. For this type of scene, it is practical to use INT./EXT. to clarify this.

Providing these small details in your scene headings may seem overkill, but they are fundamental to how a director and producer plan the shoot and coordinate wardrobe, hair, and makeup for continuity purposes.

A scene taking place at nighttime, for example, would mean organizing a night shoot and the necessary equipment required.

Action Lines

Directly below the scene heading, comes the action lines. These should be written visually and in the present tense to describe what is happening on screen. Unlike prosaic writing, action lines should not be overly descriptive. Just tell the audience what is happening right in front of them.

You’re not writing the next epic novel, but a blueprint from which to create a movie. Include key details that will make other members of the production team’s lives much easier.

For example, if you have a specific prop crucial to the scene, make sure you clearly describe it. Precision is key to achieve the look and atmosphere you want, especially when writing more complex scenes such as fight sequences or car chases.

You will notice in the above example that we have capitalized the names of the first two characters: JAMES and SHADOWY FIGURE. All characters’ names must be capitalized within action on their first appearance. This allows the crew to easily identify when a character first appears in the script and plan the shoot accordingly.

Important props and sound effects can also be capitalized, but this is not always necessary. Be selective when using capitalization in this way as there is nothing more off-putting than random words in capital letters appearing randomly on the page.

Character Names

When dialogue appears in a scene, we need to identify the character speaking. You don’t necessarily need to use their name, but what best identifies them.

For example, if your character’s name is John McClane (Die Hard franchise), a determined police detective, he would be identified in his work as McClane. Hence the best way to present him would be by that name. If John McClane was instead the lead in a carefree romantic comedy, you may refer to him as John.

If your character has an alias, such as Peter Parker, more commonly known as Spiderman, you would refer to each separately depending on who they are portraying in the scene even if they are in reality the same person. Alternatively, when Peter Parker becomes Spiderman, a slash could be incorporated e.g. Peter Parker/Spiderman whenever he’s in his superhero get-up.

As you will see from our above example, James is introduced in capitals at the start of the scene on his first appearance, his first line of dialogue prefaced by the same name. We can clearly see that James is meant to be speaking.

Dialogue

Dialogue always sits centrally on the page, directly underneath the character name. This clearly differentiates it from the action lines and allows actors to easily identify when to speak as well as write any notes in the margins either side.

As you can see from our example, we have a dialogue exchange between the two characters, both their names matching those given in the action lines.

Writing dialogue is a craft in itself, and is used to reveal character emotion, motivation, and goals. Find out more about how to format compelling dialogue in our article here.

Sometimes, we may wish to add extensions onto character names to detail how the audience hears the dialogue.

In the example below, you will notice CONT’D at the end of the Shadowy Figure’s character name. This shows that the character’s dialogue line has been interrupted by action and that they should continue like they would.

James’ following dialogue line is detailed as O.S. meaning off screen and is used to show a line heard and by the other characters on screen but only heard by the audience. You could also use O.C. in this scenario, meaning off camera.

Voice over (V.O.) can be utilized when a character speaks over the action but only the audience hears. Voice over can be an overused technique in screenwriting so make sure you are using it to push a story forward, and not purely as an expository device.

If your character is speaking into a device such as a phone, as well as another on-screen character, you can use INTO *DEVICE* to differentiate the two types of dialogue.

Parentheticals

While extensions tell us how the audience hears the dialogue, parentheticals tell us how the lines are spoken. Intended for actors to help direct them to their characters’ internal thought processes and emotions, parentheticals help create a dynamic and complex scene.

Parentheticals can be emotions, or actions for actors to perform as they speak the line of dialogue.

We have used both an inflection and action in the above example to give the actors an indication, both of the emotion behind their dialogue, and what they’re doing whilst talking.

Of course, the Shadowy Figure could be laughing, crying, shouting, whispering, or delivering the line in any other way. As the screenwriter, it is up to you to indicate where you feel a line needs to be delivered in a certain way.

It is crucial not to overuse parentheticals, however, as too many can make a script look crowded. It also doesn’t allow the directors and actors to interpret the story and the characters from their perspective. Remember, filmmaking is a collaborative process.

Learn more about parentheticals in our dedicated article – click here!

Transitions

While parentheticals indicate dialogue details to the director and actors, scene transitions guide the editor in how to switch between scenes.

Similar to parentheticals, you don’t want to overcrowd your script with them and stifle your editor’s creativity but if there’s a particular way you envision specific scene changes, then make them known.

Transitions are always positioned on the right-hand side of the page before the next scene heading as you’ll see below.

A great way to use scene transitions is when you want a high impact change from one location to another. Let’s take a look at some examples of scene transitions:

CUT TO:

This is the most widely used transition, marking the end of a scene. Many TV shows use this transition to indicate a commercial break/act break. Again, you don’t need to use this at the end of every scene, and only when it’s absolutely necessary.

SMASH CUT TO:

Smash cuts are essentially Cut to but amplified. They are used to emphasize an abrupt end to a scene, a metaphorical stop mid-sentence, or even a real one, if a character’s dialogue is interrupted.

DISSOLVE TO:

Does what it says on the tin. This transition is used to ‘dissolve’ from one scene to the next. It’s softer than the previous two examples and is great in showing a passage of time.

MATCH CUT TO:

This is one of our favorite transitions where the last shot in the previous scene matches the first shot in the next. This could be visually or through sound.

A prime example of a match cut using sound is in Mean Girls (2004) when Regina discovers the Kalteen bars that Cady recommended to her to lose weight, make her gain weight. In her rage she screams a scream that begins outside Cady’s house and ends in her own.

The transition is a mere second, but shows a passage of time, both showing how long Regina has been screaming for, and keeping the audience engaged in the action.

Whilst an effective transition, match cuts are one of the trickiest to edit, so again, ensure it’s necessary and adds to your story.

INTERCUT:

Intercuts cross back and forth between two different scenes/locations. The most common use for intercuts is a phone call between two or more characters.

This scene from John Wick (2014) is highly effective in showing character through a phone call. You’ll notice that John, the protagonist doesn’t say a great deal, yet we can understand him through his body language and non-verbal cues.

From the caller’s perspective, we also see his body language doesn’t match up with his tone of voice, leading us to understand his discomfort.

Subheaders

Sub-headers are mini scene headings that break a scene into separate places or times. When using screenwriting software, these will still come under scene headings.

Notice the sub-header in capitals between the two sets of action lines. We are still on the beach, but time has elapsed. This allows the script to flow and indicates to a director that they won’t need to change locations for this change from one time frame to another.

Shots

Shots are usually formatted within the action lines and highlight a specific way something is presented on screen through camera angles, movements, or shots.

They are mostly adopted by writer-directors who want to note down a specific vision, but sole writers can also use them to direct the director to a particular visual if they see fit.

Too many indicated shots can take readers out of the story you are trying to tell, so try not to get too carried away and leave the directing to the director as much as you can.

Let’s return to John Wick (2014) and look at the opening page of the script. You will see writer Shay Hatten has indicated an extreme close up to emphasize the Makiwara board and the fist connecting with it.

This introduces us to the protagonist, showing his strength and abilities. Our interest is immediately peaked as we see John’s might, hooked into what his other potential capabilities could be.

Notice the close up shot is indicated in capitals and bold in this instance within the action lines.

Montage

Montages are a popular device used to show a passage of time through various events. There are a few different options you have when formatting montage, which you can explore in greater detail here.

Many writers like to format montage using bullet points, rather than writing separate scene headings for each new moment. Take this example from Pretty Woman (1990) when Vivian is trying on various outfits:

Writer Jonathan Frederick Lawton has used a sub-header to introduce the montage, then listing each moment in separate paragraphs. This works especially well in montages that take place in one location.

If we compare the Pretty Woman montage to the training montage from Rocky (1976), we’ll see that each moment is given a new scene heading as time passes.

Realistically, montage formatting is very much a stylistic choice dependent on you as a writer and how you prefer to write montage. All that matters is the action is clear.

Chyrons

Text appearing over the screen, such as a movie title, language subtitles, or to indicate a specific time and place are known as chyrons.

In our example script, we’ve used three options for chyrons. All are written in capitals, and all can be used depending on your personal preference. SUPER stands for superimposed.

Writing a Screenplay

Now that we’ve covered all the elements of a screenplay and their formatting conventions, it’s now time to start writing. You shouldn’t need to manually format and move margins around to produce an industry standard script.

Screenwriting software such as Celtx does all the hard work for you so you can focus on crafting a smash hit of a movie or TV show. Whatever your choice of software, free or paid, we recommend finding one that works for you as a writer and helps you be productive.

FAQs

As with all creative pursuits, how long is a piece of string? If you are about to write your first screenplay, it will probably take more time than someone who’s been writing scripts for 25 years. The key thing is to go at your own pace. No writer or script project is the same.

Yes. Every screenplay should start with a title page that includes your script’s title, your name, and contact information. Celtx automatically formats a professional title page for you.

All title pages will include:

– Script title

– Name of writer

– Space for revision details

– Space for contact details and any copyright information (bottom left corner)

Learn more about how to format a title page here.

Most screenplays follow a three-act structure: setup, confrontation, and resolution. Within that framework, scenes are built using elements like slug lines, action lines, dialogue, and transitions.

A feature film script typically runs between 90 and 120 pages — roughly one page per minute of screen time. Celtx’s page count tools help you track pacing as you write.

While you can technically write a script in any word processor, screenplay software like Celtx handles formatting automatically—so you can focus on storytelling instead of margins and indents.

Test it with beat sheets or scene outlines. Tools like Celtx’s Story Development features help visualize your story flow and identify gaps before you start rewriting.

Conclusion

Every great screenplay starts with structure — but it’s how you use it that makes your story stand out. Structure gives you the framework, not the formula. Once you understand the rhythm of a scene or the weight of a transition, you can start bending the rules in ways that feel intentional and bold.

Celtx gives you the space to experiment — to draft, revise, and rebuild your story until every beat lands just right. Because learning your craft isn’t about getting it perfect the first time — it’s about finding your flow and building confidence with every page you write.

Ready to start writing (without worrying about structure)? Sign up for Celtx today!

Up Next:

How to Format a Script | A Step-by-Step Guide

Now that you’ve mastered structure, make sure your formatting matches industry standards. Learn how to present your story professionally—so nothing stands between your script and the screen.