Every great story, whether on the big screen or the small, is defined by its conflict. Without obstacles, a journey loses its purpose, and without opposition, a hero’s triumph feels hollow. This is where the antagonist steps in — not merely as the “bad guy,” but as the central force that challenges your protagonist and, in doing so, reveals the deepest truths about them.

The dynamic between a protagonist and their antagonist is the engine of narrative. It’s a relationship built on clashing goals, opposing ideologies, and a constant push-and-pull that drives the plot forward. Too often, antagonists are seen as one-dimensional villains, but the most memorable ones are as complex and well-developed as the heroes they face.

In this guide, we’ll delve into the art of creating a compelling antagonist, exploring the different forms they can take and how their presence can elevate your storytelling to the next level. We’ll provide you with the professional guidance you need to make your scripts shine, no matter where your creative journey begins.

Table of Contents

- What is an Antagonist?

- Types of Antagonists: A Framework for Writers

- How Modern Antagonists Enhance Storytelling

- Compelling Antagonists: Case Studies from Film and TV

- Tips for Writing Compelling Antagonists

- FAQs

What is an Antagonist?

At its core, an antagonist is the primary source of conflict for the protagonist. This opposition doesn’t always have to be a person. The antagonist can be a force of nature, a societal institution, a character’s own inner demons, or even a rival who isn’t inherently evil. The role of the antagonist is to observe the protagonist’s intentions and actively interfere with their ability to achieve their goal. This calculated opposition, whether conscious or not, is what creates tension and stakes.

It’s a common misconception that an antagonist must be “evil.” While many iconic villains fit this description, like Cruella de Vil or Scar, this narrow view limits the possibilities for profound storytelling. A hurricane, for instance, isn’t “bad” but can be a powerful antagonist for a character trying to save a community. A rival in a sports film isn’t “evil,” but their competing ambition creates the necessary conflict.

Modern narratives have increasingly moved away from simple binaries of “good vs. evil” to explore more nuanced and empathetic antagonists. This approach challenges the audience’s assumptions and forces them to confront the complexities of human motivation.

For a deeper dive into the psychological role of the antagonist, consider exploring academic articles on narrative theory.

Types of Antagonists: A Framework for Writers

Choosing the right type of antagonist is crucial for your story. The conflict they present should be perfectly suited to the protagonist’s journey and goals, creating the most compelling obstacles possible.

Personified Antagonists

These are antagonists who are human or physical beings with their own motives, goals, and flaws.

- The Villain: The most traditional form of antagonist, the villain is the clear “bad guy.”

- The Evil Villain: Driven by malice or personal gain, they are the clear and present danger. Examples include Miss Trunchbull from Matilda or Voldemort from Harry Potter, whose pursuit of power is a direct threat to the hero.

- The Supervillain: A heightened form of the villain, often with superhuman powers, serving as the inverse of a superhero. Think of Magneto (X-Men) or Hela (Thor: Ragnarok).

- The Mastermind: This antagonist relies on intellect, manipulation, and intricate schemes rather than brute force. They are a psychological threat. A prime example is Professor Moriarty from Sherlock Holmes or Hannibal Lecter from The Silence of the Lambs, who can exert immense power even while contained.

- The Henchman: These characters serve a primary antagonist, but their loyalty can be complex and their own goals may inform their actions. The Death Eaters in Harry Potter are a perfect example; while they serve Voldemort, characters like Bellatrix Lestrange and Lucius Malfoy have their own ambitions and drives.

- The Evil Villain: Driven by malice or personal gain, they are the clear and present danger. Examples include Miss Trunchbull from Matilda or Voldemort from Harry Potter, whose pursuit of power is a direct threat to the hero.

- The Anti-Villain: A complex and modern archetype, the anti-villain has justifiable goals from the audience’s perspective, but the methods they use to achieve them are morally questionable. This blurs the line between hero and villain and creates audience empathy.

Draco Malfoy from Harry Potter is a great example. His actions are rooted in his troubled upbringing, making him an antagonistic force, but his eventual inability to commit murder reveals a deeply conflicted character.

Thanos from the MCU is another, whose goal of universal balance, while horrific in its execution, is born from a twisted sense of necessity.

Non-Personified Antagonists

Sometimes, the greatest conflict isn’t with a person at all.

- The Protagonist as Antagonist: This is a powerful form of internal conflict where the hero’s own flaws, fears, or past traumas are the main obstacle. In The Catcher in the Rye, Holden Caulfield’s struggle with his own insecurities and mental health prevents him from reaching his goals more effectively than any external force. This requires a strong backstory and a deep understanding of character psychology.

You might find this article on character flaws helpful for developing this type of antagonist. - Societal/Institutional Antagonists: The protagonist fights against the norms, rules, or injustices of the society in which they live. The Capitol in The Hunger Games and the oppressive regime of the Republic of Gilead in The Handmaid’s Tale are perfect examples. The heroes must challenge the very fabric of their world to succeed.

- Forces of Nature: Natural disasters like hurricanes, floods, or even the vastness of an unpredictable ocean can be a powerful source of antagonism. In Life of Pi, the ocean is a character in itself, its raw power forcing the protagonist to adapt, survive, and learn.

How Modern Antagonists Enhance Storytelling

The evolution of the antagonist from simple “bad guy” to a complex, multi-faceted character is a testament to the sophistication of modern storytelling. This shift allows for narratives that are more empathetic, thought-provoking, and deeply human.

Humanizing the Villain

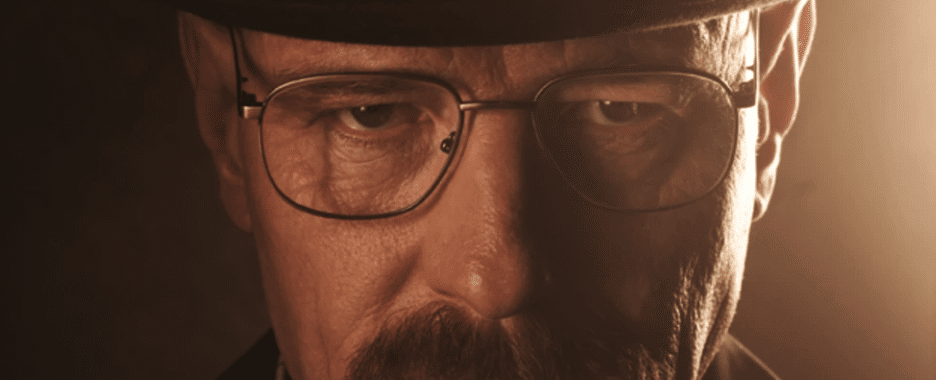

When an antagonist’s motivations are relatable, it creates a sense of unease and empathy in the audience. Cersei Lannister in Game of Thrones or Walter White in Breaking Bad are prime examples. Their backstories and circumstances, though they don’t justify their actions, provide a human context that makes them more compelling than a purely evil character. As writers, this character development allows us to explore deeper themes about morality, choice, and the fine line between right and wrong.

Driving Character Development

An antagonist should be a mirror to the protagonist. Their opposition should force the hero to confront their own weaknesses and grow. By pushing the protagonist to their limits, the antagonist facilitates the hero’s transformation, ensuring the story is not just a series of events, but a journey of self-discovery and evolution.

Reflecting the Times

Antagonists often embody the societal fears, anxieties, and critiques of their era. The oppressive institutions in stories like 1984 or The Handmaid’s Tale are a direct reflection of historical and contemporary concerns about power, control, and autonomy.

If you’re considering a career in screenwriting, you might find more resources on character development from a film school’s screenwriting curriculum.

Compelling Antagonists: Case Studies from Film and TV

Let’s take a look at some exemplary antagonists and dissect what makes them so effective.

Anton Chigurh (No Country for Old Men)

Anton Chigurh is not driven by greed, revenge, or a complex backstory. He is a force of nature, a personification of inevitable violence and random fate. What makes him terrifyingly compelling is his complete lack of discernible humanity or conventional motive. He kills with the same detached calm whether it’s a target or a random gas station clerk. This makes him unpredictable and impossible to reason with, serving as a stark, amoral antagonist against Llewelyn Moss, who desperately tries to escape his grasp.

His compelling nature comes from being an unwavering, elemental force that defies easy categorization.

Nurse Ratched (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest)

Nurse Ratched is a master manipulator, an institutional antagonist personified. She rarely raises her voice or resorts to overt physical violence, yet her control over the patients at the mental institution is absolute and suffocating. Her power lies in her bureaucratic authority, her calm demeanor, and her ability to exploit the vulnerabilities of others.

She represents the oppressive system itself, using psychological warfare to enforce conformity and extinguish individualism. Her compelling nature stems from her chilling, calculated emotional violence and the way she strips her patients of their autonomy, creating a profound conflict with McMurphy’s rebellious spirit.

Killmonger (Black Panther)

Erik Killmonger is a quintessential anti-villain. His goal, which is to empower oppressed people globally by sharing Wakanda’s advanced technology, is deeply sympathetic. However, his methods, which involve violence, war, and overthrowing the established order, place him in direct opposition to T’Challa.

What makes him so compelling is that his pain and anger are justified, rooted in the historical injustices suffered by his family and people. He forces the audience to question T’Challa’s passive approach and challenges the very core of Wakanda’s isolationist policy. He is compelling because he isn’t simply “evil”; he represents a path that could have been taken, and his arguments resonate long after the credits roll.

Cersei Lannister (Game of Thrones)

Cersei’s character embodies a blend of personal and political antagonism. Her primary motivation throughout Game of Thrones is the protection and advancement of her children, coupled with an insatiable desire for power within a brutal world.

While her actions are often ruthless and morally reprehensible, her fierce maternal love provides a humanizing context. She is a master of political manipulation and strategic thinking, constantly adapting to circumstances and outmaneuvering rivals. Her compelling nature arises from her complexity: a character capable of both immense cruelty and profound devotion, making her far more than a simple villain.

Tips for Writing Compelling Antagonists

Crafting a powerful antagonist is one of the most important things you can do to elevate your screenplay. Here are some key tips to keep in mind:

1. Give them a clear goal

Your antagonist should want something specific and tangible. This goal doesn’t have to be malicious; it just needs to be in direct conflict with your protagonist’s goal. A simple, selfish goal is often more relatable and compelling than a vague desire for “world domination.”

2. Define their motivation

Why do they want what they want? Is it for love, revenge, power, survival, or a misguided sense of justice? Their motivation is their driving force and the key to making them more than a caricature. An antagonist with a strong “why” is far more interesting than one with a strong “what.”

3. Make them the hero of their own story

From their perspective, their actions are justified. They believe they are doing the right thing, or at the very least, a necessary thing. This internal logic makes them feel real and complex, not just evil.

4. Give them strengths and weaknesses

A flawless villain is boring. A compelling antagonist should have their own skills and abilities that make them a formidable opponent, but also a fatal flaw or vulnerability that the protagonist can exploit. Their weaknesses can be physical, emotional, or ideological.

5. Mirror the protagonist

Create a parallel between your hero and your antagonist. They may share similar backgrounds, skills, or even values, but their choices and methods are what set them apart. This “dark mirror” reflection forces the protagonist to confront their own potential for evil and makes their journey more meaningful.

6. Don’t make them evil just for the sake of it

The most compelling antagonists are not born evil; they are products of their environment and circumstances. Their story explains how they came to be the way they are, making their journey understandable, if not forgivable.

7. Challenge their beliefs

A great antagonist can not only oppose your protagonist’s goals but also challenge their core beliefs. This kind of ideological conflict creates a deeper, more thought-provoking narrative.

Struggling to develop strong characters? Download our free character questionnaire and get to know your characters on a deeper level.

FAQs

While a villain is a type of antagonist, the terms are not interchangeable. An antagonist is any force, person, or element that opposes the protagonist. A villain is specifically a malicious or evil antagonist, and their primary motivation is often to cause harm or chaos. All villains are antagonists, but not all antagonists are villains.

Yes, absolutely. This is a common and powerful storytelling device. When a character’s greatest obstacle is their own inner conflict, self-destructive behavior, or a tragic flaw, they are acting as their own antagonist. This type of internal conflict can lead to some of the most profound character arcs in cinema.

A story can have one central antagonist and several secondary or minor antagonists, but it’s important not to overload the narrative. A single, powerful antagonist often works best in short-form narratives or films, while a series of antagonists or a main antagonist with several henchmen can work well for TV series or extended sagas. The key is to ensure each antagonistic force serves a clear purpose in the plot.

In many cases, yes. Creating an antagonist who is a “dark mirror” of the protagonist—a character who has similar goals but different, more destructive methods—is a highly effective way to create conflict. This forces the protagonist to confront what they could become if they strayed from their moral path, adding significant depth to the story.

Modern television and film are rich with examples. Some of the most notable include Killmonger (Black Panther), who has a valid political motivation for his radical actions; Walter White (Breaking Bad), whose desperation and pride turn him into a criminal mastermind; and Cersei Lannister (Game of Thrones), whose actions are driven by a fierce love for her children in a brutal, patriarchal world.

Conclusion

The antagonist is the unsung hero of your script. Strange thing to write, but it’s true! They are the catalyst for change, the architect of conflict, and the force that pushes your protagonist to their true potential. By moving beyond a one-dimensional “bad guy” and crafting a nuanced, complex character with their own motivations, you can build a more engaging and emotionally resonant narrative.

Remember, the goal is not to make your antagonist easy to defeat, but to make their presence so compelling that their opposition becomes the very heart of the story. Mastering the art of the antagonist is a skill that will serve you throughout your career.

Ready to bring your script to life? Celtx offers the tools you need to write, plan, and produce your creative vision. Start your free trial and master the craft of screenwriting today!

Up Next:

Protagonist vs. Antagonist: Storytelling’s Core Conflict

Great stories are built on conflict. See how protagonists and antagonists work together to shape your narrative in our guide to Protagonist vs. Antagonist.