Montages are everywhere—from fast-paced action sequences to emotional romantic reveals—but what exactly makes a montage work?

In this blog, we’ll break down the basics, explore its cinematic roots, and dive into the many ways filmmakers use montage to move stories forward.

Want to write a montage into your script? Try Celtx’s scriptwriting tools for free.

In This Article

- What Is a Montage?

- Where Did Montages Come From?

- Types of Montage

- How to Plan an Effective Montage: Visuals, Sound, and Transitions

- How to Create a Successful Montage

- Examples of Montages

- FAQs

- Conclusion

What Is a Montage?

By definition, a montage is “the process or technique of selecting, editing, and piecing together separate sections of film to form a continuous whole.”

Montages are used across genres, and can be effectively employed for countless reasons. Whether it be for comedic effect, flashback, establishing atmosphere, providing exposition, progressing plot, or indicating the passage of time, a montage is a powerful storytelling tool.

Where Did Montages Come From?

The term ‘montage,’ which derives from the French ‘monter,’ meaning ‘to climb or get up onto,’ has been in the cinematic lexicon since the 1920s. However, early versions of the technique existed years before there was a specific word for it. The term itself came into popular usage among the Soviet avant-garde community in the 1920s, most notably thanks to the work of two Russian theorists and filmmakers, Lev Kuleshov and Sergei Eisenstein.

The ‘Kuleshov effect,’ was established by, you guessed it, Lev Kuleshov in the early 1920s. This phenomenon noted the profound effect the arrangement of shots can have on a viewer’s emotional experience.

Following Kuleshov’s lead, Sergei Eisenstein studied montage further. He determined that a film montage would, by definition, be made up of small pieces that lacked meaning alone but gained significance once strung together. Thanks to Kuleshov and Eisenstein’s critical work, filmmakers in the Soviet Union began using and experimenting with this technique.

As Soviet power became increasingly strict and repressive, the usage of montage became less popular, giving way once again to simpler, stripped down techniques. Though there were some instances of montage in films made in the leadup to and during World War II, it wasn’t until American and British filmmakers started putting their own spin on this tool in the 1950s that it regained popularity and continued to evolve.

The craft of filmmaking has come a long way since the Soviet avant-garde era, but the use of montage is no less significant. Nowadays, there’s no shortage of inspiration to be tapped from existing films and TV, which have found many creative, out-of-the-box ways to execute this technique.

No matter what type of story you’re looking to tell, you’ll find that incorporating a montage will help you keep your rhythm varied, your visuals engaging, and your plot efficient.

Types of Montage

Montages can serve many purposes, but most fall into a few recognizable categories. These aren’t strict boxes, but they offer a helpful lens for understanding how and why a montage works.

1. Establishing Montage

In an establishing montage, one of the most common types, the world of your protagonist is revealed via an introductory sequence. As any filmmaker knows, establishing exposition within the first several minutes of your story is vital, however doing so can easily become trite and heavy handed.

A montage, then, switches the standard up while still conveying all the essential expositional information. One such example is found in Trainspotting.

In this sequence, Ewan McGregor’s dry, disinterested voiceover monologue accompanies an introduction to each member of his friend group in their natural habitat. By the end of the montage, McGregor’s drug-fueled lifestyle is revealed, setting the scene for the story to come.

2. Metric & Rhythmic Montage

Two similar types of montage defined by our Soviet pal Eisenstein, these categories intercut a series of identically or similarly timed shots for rhythmic effect. This style of editing is varied, but in many cases is used to increase the action, drama, or excitement of an otherwise dull sequence.

A great example of this comes from one of the all-time great masters of montage, Edgar Wright, in his film Hot Fuzz. In what could have been a drawn out, boring sequence, Wright instead cuts together quick, specific shots of his protagonist moving to Salford.

This montage serves as exposition, yes, but it does more than that given its artful editing. It drops the audience right into the unique atmosphere of the film, while still effectively establishing the facts.

3. Thematic Montage

In this type of montage, rather than pulling together shots directly related to your story, filmmakers combine images which convey a larger concept or fit a central theme. This type of montage can be especially effective at the start of a script to give viewers a sense of the story they’re about to watch, or at the conclusion to reinforce the theme you’ve been exploring.

An effective example can be found in the opening and final scenes of Love Actually.

Inspirational music and Hugh Grant’s voiceover in the opening, and “God Only Knows” by The Beach Boys in the final scene, accompany a series of clips at Heathrow Airport of people reuniting with loved ones. The theme of the film is love, and this sequence gives us a taste of the feel-good stories to come.

4. Sequential Montage

In sequential montage, a much longer timeline is condensed into a single sequence. Think of this type as a carefully executed highlights reel of whatever event or series of events you’re attempting to capture.

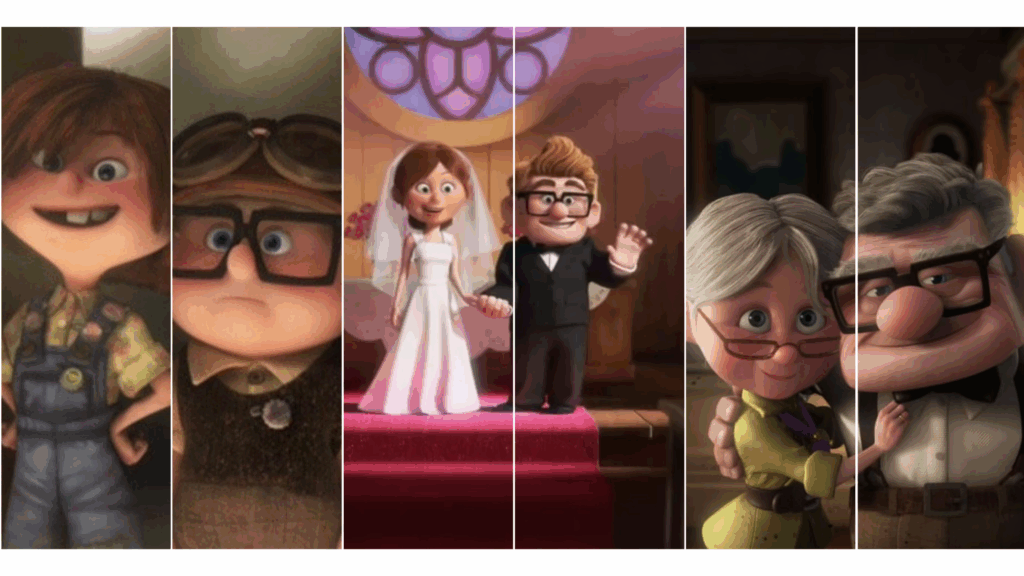

One incredible example of this type of montage can be found in Pixar’s tear-jerker, Up. In just over 4 minutes, the entire lifespan of a relationship, from marriage to funeral, and everything in between, is conveyed with no shortage of detail or emotion.

5. Comparison Montage

In comparison montage, two or more contrasting stories or visuals are intercut in order to amplify the drama. This type can come in handy at any point in your story.

One of the most famous examples of this type can be found in The Godfather. In this montage, the film flicks between a sacred baptism and a series of brutal murders.

At this turning point in the story, viewers understand that there is no turning back for Michael Corleone, who has now become The Godfather. The gravity of his choice is made even more dramatic paired with the baptism scene, which represents birth and innocence.

Already thinking about how a montage could elevate your script?

Start outlining your sequence with Celtx’s beat sheet tool.

6. Transformation Montage

Whether it’s a makeover or a training sequence, this type of montage is used to convey hard work, trial and error, or repeated failure. In this variety, the musical accompaniment is generally your key partner in crime.

One obvious, iconic example of transformation montage can be found in Rocky. Though he starts scrappy and determined, Rocky, as the accompanying lyrics suggest, gets progressively stronger until he emerges victorious atop the Philadelphia Art Museum steps.

How to Plan an Effective Montage: Visuals, Sound, and Transitions

There are endless creative possibilities when it comes to putting together a montage, but the basic elements which will make your sequence engaging remain the same across the board.

First and foremost, given that film is a visual medium, the actual images you as a filmmaker choose to include in your montage are extremely important. Will your montage include only closeups? Will there be motion, or will the sequence be comprised of a series of stills? Do the shots have contrasting or complimentary colors and lighting? The aesthetic of your sequence should be your first consideration when putting a montage together.

Once you have a clear sense of what your montage will look like, you’ll need to turn your attention to sound. Will there be music, dialogue, or voiceover laid on top? Or, will silence or diegetic sound aid the storytelling?

Related Celtx Blog: How to Write a Short Story: A 6 Step Guide with Examples

The last aspect to consider in putting together your montage is the transitions. This includes pacing and cut styles, which will be choices you make in the edit. What feeling are you hoping to evoke in the audience as they watch? Excitement? Sadness? Anxiety? This will inform the speed of your montage, and your method of transitioning from one shot to another.

How to Create a Successful Montage

So now you’re a pro on the elements of an effective montage, but how do you actually sit down at your laptop and write it?

Before you get ahead of yourself, as is the case with any writing, you should start with an outline. What are you trying to say over the course of this montage? Approach this sequence in the same way that you would a standard scene – what’s the overarching event, or events, and what change(s) occurs from start to finish?

Once you have a clear overview, you can start getting specific through storyboarding. Though your script likely won’t reflect the final product when all is said and done, it’s still important that the blueprint is there. What do you envision the sequence of visuals will look like? Capture the sensation you want your viewers to feel in the language you use on the page.

On a technical level, there are no strict rules for formatting a montage. You can keep it short and sweet, or go into more detail. You can put the entire sequence below one scene heading, or you can use several.

(Want a deep dive on formatting techniques? We’ve got a blog for that—stay tuned at the end of this post.)

Examples of Montages

As evidenced by the superb examples already covered, there’s plenty of inspiration to be drawn from filmmakers that have come before you as you set out to tackle your own montage.

Montage isn’t limited to one style or emotion—it spans genres and tones. Below, we’ve gathered examples from drama, action, comedy, and romance to show the technique in action.

Montages in Drama

In The Breakfast Club, the detention dance scene arrives at the point in the story when the disparate characters are, against all odds, finally coming together. This montage sees all of the detention-goers dancing, having fun, and connecting. It’s effective at showing, not telling, and it’s also a lot of fun.

Equally artistic and creative, this brief, rhythmic montage from Requiem for a Dream is assembled to maximize emotional impact and mirror the sensation of taking drugs. The closeup visuals paired with accompanying sound bytes serve as an introduction to the state of mind the characters are in.

Montages in Action

Second only perhaps to Rocky, the training sequence in The Karate Kid is iconic for a reason. In this montage, Daniel goes from novice to pro with the help of Mr. Miyagi’s regimented, unexpected techniques.

A more recent example, in Edge of Tomorrow, montage is used to show Tom Cruise’s character dying over and over again. As the pattern continues, much like in a training montage, he gradually learns and improves.

Montages in Comedy

Another master of montage, Wes Anderson creates entertaining, aesthetically specific sequences, like this one in Rushmore. What better way to illustrate that his protagonist is a quirky over-involved overachiever than through this comedic series of vignettes?

Some of the best comedic montages are parodies of existing tropes. One of the most side-splittingly funny examples of this is found in Wet Hot American Summer. Poking fun at the training montage, especially the ones in The Karate Kid and Dirty Dancing, this sequence resonates due to its specificity and makes you laugh thanks to its absurdity.

In Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, montage is used to increase the urgency of Ferris’ race to make it home before his mother does.

This sequence cuts between his mother and sister in the car, and Ferris running, trying to avoid being seen along the way, through the neighborhood. Like in many effective montages, it plays with pacing. When Ferris races past two bikini-clad women, rather than continue running, he can’t help but turn around and say a flirtatious hello.

Montages in Romance

If you’re looking for an introductory montage which sets up the premise of the film and the attitude of characters with a light touch, look no further than 500 Days of Summer.

This montage is two-fold, starting with Tom’s voiceover monologue which establishes him as a hopeless romantic and Summer as a jaded pragmatist. Visuals of both characters at the office are intertwined with visuals of each of them as children. Following this sequence, the opening credits roll on top of side-by-side actual home video footage of both actors.

Yet another training montage that hits it out of the park, Dirty Dancing is an obvious pick. In this musical sequence, Baby gradually improves as a dancer with Johnny’s help. This montage serves not only to show Baby’s dance skills growing, but also the attraction between them.

Hugh Grant makes yet another appearance in one of the best rom-com examples of a montage which conveys time passing, in Notting Hill. As Grant walks down London’s Portobello Road, the seasons change around him. The musical choice, “Ain’t No Sunshine,” further indicates the story here – he misses Julia Roberts desperately and life grows monotonous without her.

FAQs

Still confused? Here are some quickfire answers to some frequently asked questions:

How Do I Make a Montage Emotionally Engaging?

Music/sound effects/voiceover, pacing, and well-framed and ordered visuals are all important parts of making an emotional montage tick. However, it is a combination of all of these elements that create a winning montage. No single element can do it all. The placement of your montage in your story is also worth considering. Is it most impactful at the start, the climax, the end?

Can I Use Dialogue in a Montage?

Yes, you absolutely can. If you choose to use dialogue in a montage, make sure that you’re being concise.

How Long Should a Montage Be?

The length of a montage is completely dependent on what it’s covering and how it fits into the story at large. Some montages last only seconds, while others last several minutes. Less is generally more, but you also need to ensure that viewers are able to follow along. Get a second (and third!) unbiased opinion, if you’re worried your montage is running too long or is confusing.

Do I Need to Use Music in My Montage?

No. As evidenced by the montages outlined above, the majority but not all contain music. In Requiem for a Dream, for example, simple sound effects are the only sound included.

Conclusion

From Soviet theory to screenwriting structure, montage has become one of cinema’s most flexible storytelling tools. Whether you’re building tension, showing change, or creating a vibe, it’s all about how you put the pieces together.

Sitting down and writing a montage can seem daunting, but practice makes perfect. There are no hard and fast technical rules to follow, but clarity is key. If you get stuck or need inspiration, it’s always worth referring back to a successful script which has been produced and seeing how the screenwriter captured the montage on the page.

Ready to write your own montage moment? Celtx helps you visualize and organize sequences by genre, tone, and timing. Try Celtx today.

Up Next:

How to Write a Montage in a Script (With Formatting Tips)

Now that you’ve learned what a montage is and how it came to be, we’ll show you how to format a montage in your script—step by step.

Click here to continue!