Classic screenplays are classics for a reason.

Most viewers consciously or unconsciously recognize standard features. This may be a status quo thrillingly disrupted or a conflict between equally motivated heroes and villains. More often than not, though, it’s because of the three-act structure.

You’ll find one of the most used techniques for plotting stories everywhere: short stories, novels, pilots and feature films, you name it.

It defines a story’s start, middle and end but goes much further than that. It can specify plot points for each stage and moments for character growth, acting as a guide for the writer.

That might make you think it’s unoriginal (and it can be, to be honest!), but when used effectively, it’s a potent tool.

For screenwriters, it’s important we understand, even if we don’t use, the three-act structure.

As a novice writer, it’s good to have a robust and original idea or fully formed characters. But, without a well-built structure to tell that story, your script will struggle, and that’s where we come in.

In this guide, we’ll be:

- Breaking down what the three-act structure is

- Examining how the different acts work together

- Studying an example of the three-act structure

Let’s do it.

What is the Three Act Structure?

The three-act structure is a model for narrative storytelling.

It divides stories into three sections: Act One, Act Two and Act Three. This idea has its roots in Aristotle’s work Poetics, where he describes this form as one of five elements of tragedy. Despite being thousands of years old, it laid a foundation for today’s storytelling.

He emphasized that any strong story is composed of beats that follow each other consecutively. He saw that events occurred in a sequence connected by cause and effect.

Nothing just happens because it does; everything is a direct result of what came before. Different beats connect the acts, changing the narrative’s direction. Keep this in mind because we’ll return to it later.

You may be more familiar with these ideas under different names. Screenwriter Syd Field personalized this classic form with his 1978 book Screenplay. There, he labels the acts the Setup, the Confrontation and the Resolution, respectively. You’ll find similar three-act stories in The Hero’s Journey and Save the Cat!, to name a few.

The essential point of each act is that they guide the writer and audience by signposting where the story is headed.

It’s worth mentioning that screenwriters often use this structure for feature film scripts, so familiarize yourself if you haven’t yet. While the three-act structure isn’t an absolute rule for feature scripts, it’s essential knowledge for screenwriters. More importantly, it’s one of the most helpful tools in your arsenal to build your screenplay.

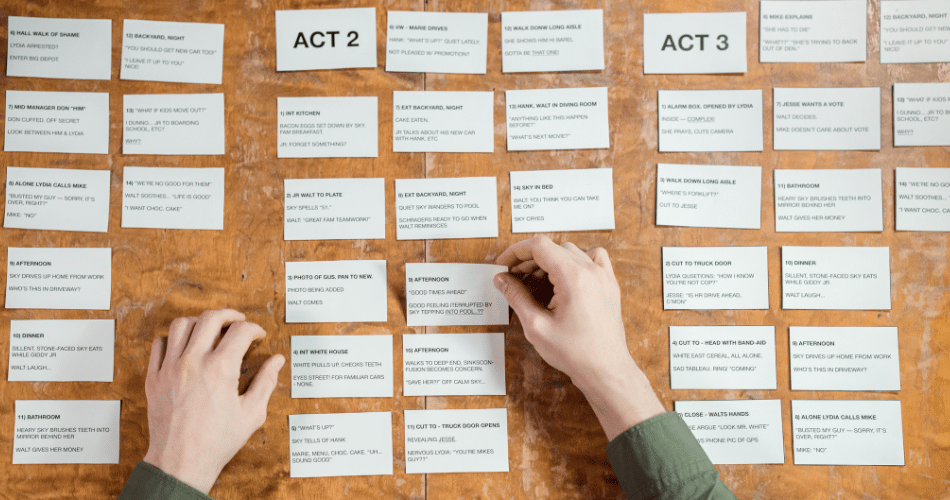

Within each act, you’ll find three story beats. Each of these beats is a moment or event that moves the story forward. With the end of each act comes a pivot for your protagonist. This drives the story in a new direction.

By sticking to three beats in each act, the final beat motivates the character to pivot. Remember cause and effect? This is how you ensure it works from start to finish.

Act One: The Setup

Your first act will constitute about twenty-five percent of your story. This is roughly 20-30 pages, depending on your script’s length.

Exposition

First off, set the stage. In your opening, you’re trying to give the reader a clear idea of your protagonist and their everyday world. We learn who your character is, what they care about and what challenges they already face. Most importantly, we know what they want.

Having a sense of what the protagonist wants is particularly critical. This is because your story is often an unexpected path to get it.

Inciting Incident

The story begins properly with your inciting incident. After that, it’s the critical moment when your protagonist is given a chance to pursue their goals.

Two clear examples are Gandalf’s visit to Bilbo and Harry receiving his letter to Hogwarts. Unsurprisingly, in the Hero’s Journey, this is often known as the Call to Adventure.

But your protagonist may not act on this moment right away. Though this is a chance for them to change their life or solve their problems, they may struggle or hesitate to act. The obstacles in their life may prevent them, or the stakes may be too high. However, a change comes soon after…

Plot Point One

With Plot Point One, the protagonist chooses to engage in the action of the inciting incident. If it’s an opportunity, this is when they take it. Often, this is a conflict that propels them into a new world.

In A New Hope, this is the death of Luke’s family. After losing his past, he’s got no choice but to take Obi-Wan’s offer to train him as a Jedi. The established, normal world of exposition is gone, so he moves forward into conflict.

The inciting incident and plot point one may occur close together. Your protagonist may try alternative solutions to their problems before committing to action. In any case, this story beat sets off the story and character in a brand-new direction. It’s the jumping-off point into your second act.

Act Two: The Confrontation

Almost always the longest of the three acts, Act Two takes up fifty percent of the story. This is about 50-60 pages, depending on the length.

Rising Action

Now that your protagonist is in a new, unexpected world or situation, they must come to terms with it. This means they encounter new obstacles, new friends and enemies. Through this process, we often discover more about the central antagonist (if there is one). In any case, this is the time to elaborate on the threat facing the protagonist.

By exploring the central conflict in this way, your protagonist proliferates. At this point, they may still be reactive and primarily respond to new situations. But as long as they continue to make choices reacting to the world, they’re not passive.

In Die Hard, this is John’s efforts to alert the police to the hostage situation. But he eventually faces a setback…

Midpoint

The name is a big clue, but this beat occurs near the halfway point of your story. This is a major development and often a negative one. It forces the protagonist to reassess their goals or take a new route. It probably raises the stakes in the process.

A good example is Edge of Tomorrow.

Cage discovers the solution to his problems, the Omega, but also that London will be attacked next if he doesn’t act. The stakes increase here. In Three Billboards, the police chief commits suicide. This reveals the futility of Mildred’s goals, causing her to reassess.

Plot Point Two

Set back by the midpoint, the protagonist now chooses to act. Finally, atey prepare to face a new mission at Plot Point Two or embark on a final challenge. Often this is the “training montage” or reflection on past lessons. But this may also be an active denial of the odds facing them as they proceed.

In any case, the protagonist snaps back from the Midpoint here. They dig into their motivations to win and achieve their goals. It’s helpful to think of Plot Point Two as a rallying cry for the protagonist.

In Joker, it’s Arthur’s preparations for the Murray Franklin Show. He’s been knocked down by the truth about his childhood and mother. But now, he’s ready to face the music.

Act Three: The Resolution

Turning to the final act, this takes up the remaining twenty-five percent (sometimes less!). This is the last 20-30 pages of your script.

Pre-Climax

With new found energy, your protagonist has faced their challenge head-on. The only problem is: it’s not working. Whatever they’ve learned up to this point fails them, and they face setbacks. The Pre-Climax puts your character to the test, and they don’t succeed (at least not straight away).

Now’s the time to introduce real doubt to your reader that the protagonist will win. Here, we see the antagonist at their strongest and the protagonist at their lowest points. This usually means reflecting on the protagonist’s most profound weakness or fear.

As you may have gathered, every negative beat has an optimistic beat in return. This sets us up for one of the three-act structure’s most important beats.

Climax

This is the ultimate moment of your story’s conflict.

Rising from the ashes, the protagonist is reborn. They use their newfound power to achieve their victory or goal. This may be using everything they’ve learned to their advantage, their natural talents or both! But by facing their fears and self-doubt, they’re victorious.

Typically, the climax is a single scene, unlike the Pre-Climax, which usually forms a sequence of events. In Die Hard, it’s John using his newly found survival skills to trick his foes by taping the gun behind his back. Then, combining that with his natural strength and shooting skills, he takes down Hans.

Denouement

And then, of course, there’s how you finish the thing. The Denouement is an important aftermath after the tension of the climax. So there are a few things to do here:

- Conclude your protagonist’s arc. Showing us what they’ve won and how they’ve changed throughout the story.

- Resolve any subplots. Secondary characters find their place in the changed world as a result of the climax.

- Clarifying the theme. Touching on the issues the protagonist dealt with in the first place.

If the protagonist hasn’t already achieved their goal, the Denouement is where it happens.

Three-Act Structure: Top Gun: Maverick

You’ll find the three-act structure everywhere in the cinema. But we’ll be looking at a contemporary example to flesh things out.

These beats are extensive, due to the film’s two-hour length. It’s obvious, but there are spoilers ahead!

Act One: The Setup

Exposition

We meet Maverick, our protagonist, in his day-to-day. Spending his time fixing up a World War II-era P-51 Mustang, he’s isolated. Through photographs on his walls, yet, we see he’s still haunted by the death of his partner, Goose.

This nods to his long-term want: to resolve the loss of his friend.

His current goal is to work as a scramjet test pilot, but we see a problem quickly emerge. Called up by Admiral Cain, the test program is ordered to stand down. The theme is underlined here in dialogue: “The future is coming, and you’re not in it.”

That’s a philosophical stake: is there a need for pilots in a world of automation?

We also learn the impact of Maverick’s failure to get over Goose’s death. While he could be at a higher station, his disobedience holds him back. This is a glimpse of his weakness: he pushes things to the limit (his “Maverick-ness”).

Nothing makes this clearer when he disregards the admiral’s order. Maverick takes the scramjet on the test and achieves Mach 10, the threshold to keep the program active. But he can’t help himself; he has to go further. The jet explodes, but Maverick miraculously survives.

Inciting Incident

Maverick should be grounded permanently, but his stunt caught the attention of the higher-ups. So he’s being reassigned to Top Gun. Arriving in “Fightertown USA,” he gets the brief from Vice Admiral “Cyclone” Simpson. The Navy has a target to destroy, but it’s a complicated and dangerous mission.

This is Maverick’s Call to Adventure, but he gets a reversal of expectations. They don’t want him to fly; they want him to teach the mission to their pilots. Naturally, he doesn’t like that and rejects the call. But there’s an upping of the stakes again: if he doesn’t take it, he’ll never fly again.

Plot Point One

At The Hard Deck beach bar, he’s still contemplating the task but runs into Penny, an old flame. This moment also introduces the pilots he might yet train (and their subplots!).

Most significantly, Maverick seeing Rooster, Goose’s son, matters most here. A flashback to Goose’s piano playing from Rooster’s identical action reveals Maverick’s desire. He wants to protect Rooster, so he accepts the call.

After being thrown out of the bar by the pilots, Maverick shocks them by turning up as their new instructor.

Act Two: The Confrontation

Rising Action

We get to grips with the team and the mission. Maverick emphasizes the danger of their task, but the cocky pilots don’t take him seriously. They think he’s too old and out of his depth (echoing the theme of being obsolete).

To prove his point, he challenges them to mock combat. To their surprise, he beats them all in a dogfight.

Secondary plots come into play here:

- Hangman (a talented but overconfident pilot) and Rooster butt head over different flying styles.

- Penny and Maverick start to rekindle their romance.

- Rooster accuses Maverick of causing his father’s death.

With big egos clashing, none of them can work together. Maverick lacks the “team player” skills to unite them (another weakness of the past).

Midpoint

Maverick’s training run simulation of the course proves a challenge for the pilots. None are able to pull it off within the time limit. The stakes get higher as the deadline for the mission edges closer. We get reminded that failure means death.

At this point, he’s called to meet Admiral Kazanzky (“Iceman”), a former pilot and close friend. He’s dying but takes the time to give Maverick the news he needs to hear: he must let go of the past.

Plot Point Two

Renewing his strategy, Maverick takes the dogfighting from the sky to the ground in a game of football with the team. Admiral Simpson expresses his doubts, but Maverick assures him it’s all part of the plan.

Maverick and Penny finally rekindle things romantically. Maverick confesses that he promised Rooster’s mother to stop him from being a pilot. But he never told Rooster because he wanted him to still like her, unlike Maverick.

Despite his best efforts, the team still find it impossible to complete the training mission. They can’t make the time or hit the target.

Act Three: The Resolution

Pre-Climax

The deadline for the mission is almost here. Maverick is pushing the pilots hard, but a sudden bird strike takes them down. Rooster’s anger boils over as he confronts Maverick, scorning him.

Frustrated by a lack of results, Simpson takes over training and grounds Maverick. His job is over. To top it all off, Iceman finally passes away. There’s no more cover left for Maverick to protect himself with.

Floundering, Maverick consults Penny. She mentors him to find a way to get back: “These are your pilots. If anything happens to them, you’ll never forgive yourself. You’ll find a way.”

Simpson lowers the mission timer (upping the stakes, increasing the chance they’ll die). But, with his mojo back, Maverick echoes his scramjet stunt. He flies the training mission unauthorized and, in front of the team, proves it’s possible to complete.

About to be reprimanded yet again, Simpson reverses expectations. Maverick is reinstated as team leader, but this time he’ll be flying the mission.

Climax

The mission arrives. Maverick picks Rooster as his wingman (sidelining a waiting Hangman). A local runway is bombed to give the team time as they set off. Despite complications (travelling slower than usual, enemy fighters are alerted), they manage to destroy the target.

But, as missiles close in, Maverick saves Rooster’s life and is shot down in the process. Believing he’s dead, the team head home. Maverick wakes up and is about to be killed when Rooster saves his life and is also shot down.

Arriving at the ruined runway, Maverick’s age and philosophy of “it’s not the plane, it’s the pilot” is put to the test. They steal an F-15, an old aircraft that only Maverick is familiar with, and escape. But they’re intercepted by the two enemy fighters from earlier.

Now working together, Maverick manages to outfly the fighters, destroying them. The wounded F-15 approaches the friendly aircraft carrier, but a final jet shows up. Maverick orders Rooster to eject, but the aged plane won’t work. However, Hangman arrives to save the day, taking out the jet. Maverick and Rooster safely crash land on the deck.

Denouement

Now back where we started, Rooster is helping Maverick restore the P-51 Mustang. Just as before, we see the image of Goose and Maverick, now next to a photo of Rooster and Maverick.

Penny arrives to meet Maverick and the two take off in the repaired Mustang. In a very literal final image, Rooster has helped Maverick fix his past and move on.

Conclusion

That’s a wrap!

By breaking down the three-act structure, we’re able to see just how effective each beat is individually. Together, they make a strong basis for almost any story to fit.

By applying this structure to your work, it can highlight pacing and beat issues for you to fix, even if you don’t use it.

And if you’re a first-time writer, Celtx has you covered. Be sure to check out their top advice for building a screenplay when you’re first starting out.